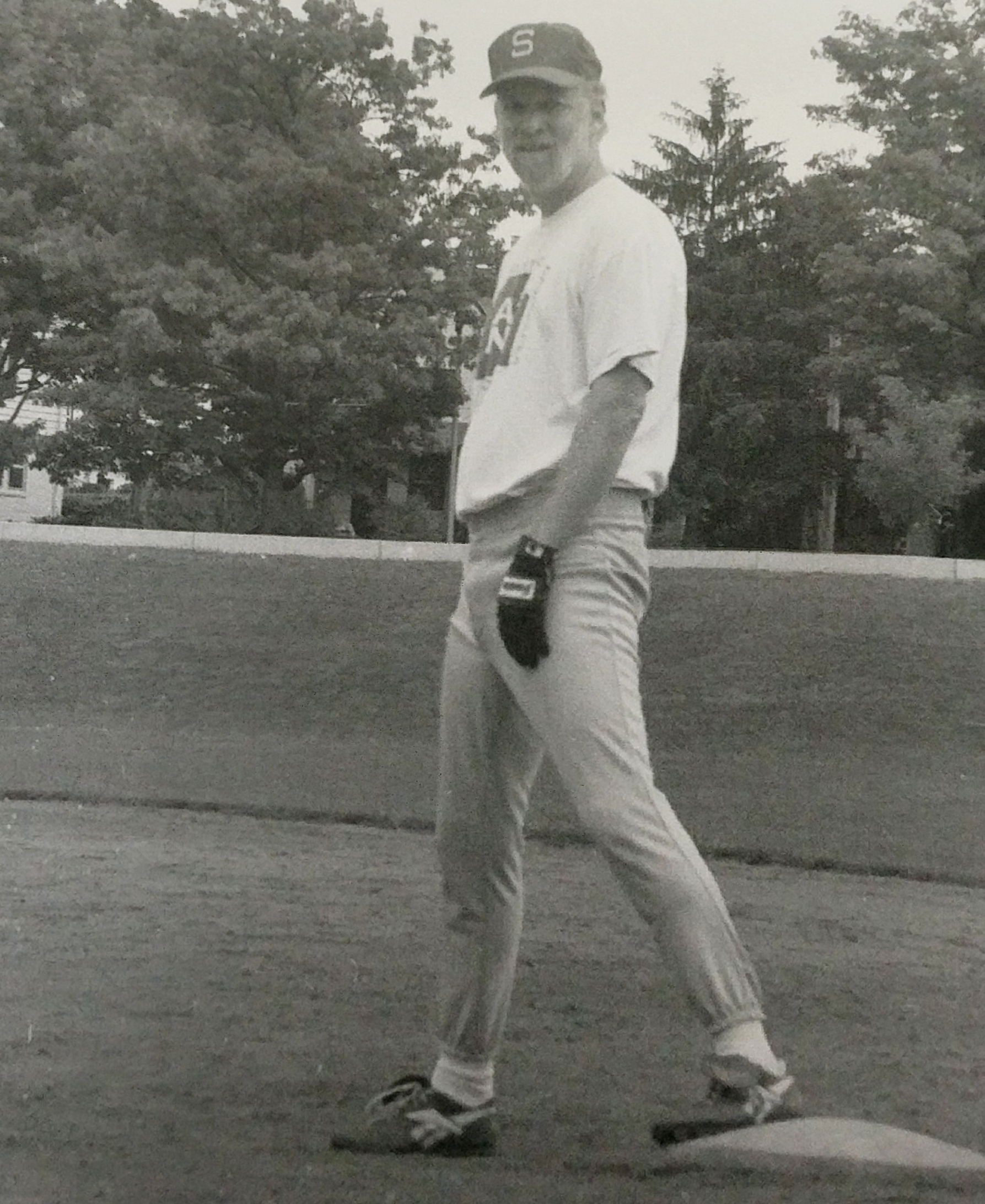

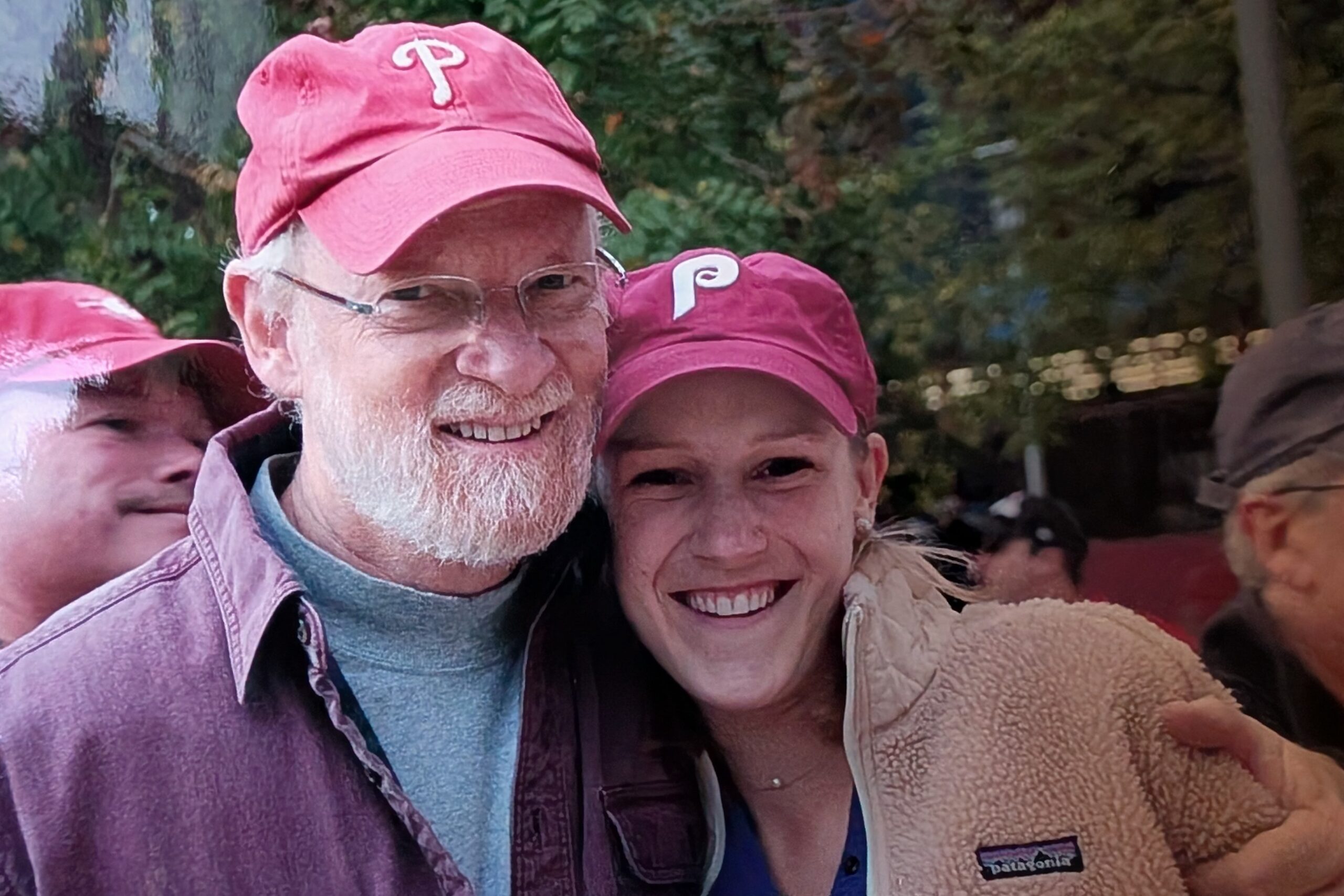

Isaiah Zagar, 86, of South Philadelphia, the renowned mosaic artist who crafted glittering glass art on 50,000 square feet of walls and buildings across the city and founded Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens, has died.

Mr. Zagar died Thursday of complications from heart failure and Parkinson’s disease at his home in Philadelphia, the Magic Gardens confirmed.

“The scale of Isaiah Zagar’s body of work and his relentless artmaking at all costs is truly astounding,” said Emily Smith, executive director of the Magic Gardens. “Most people do not yet understand the importance of what he created, nor do they understand the sheer volume of what he has made.”

His art, Smith said, “is distinctive and wholly unique to Philadelphia, and it has forever changed the face of our city.”

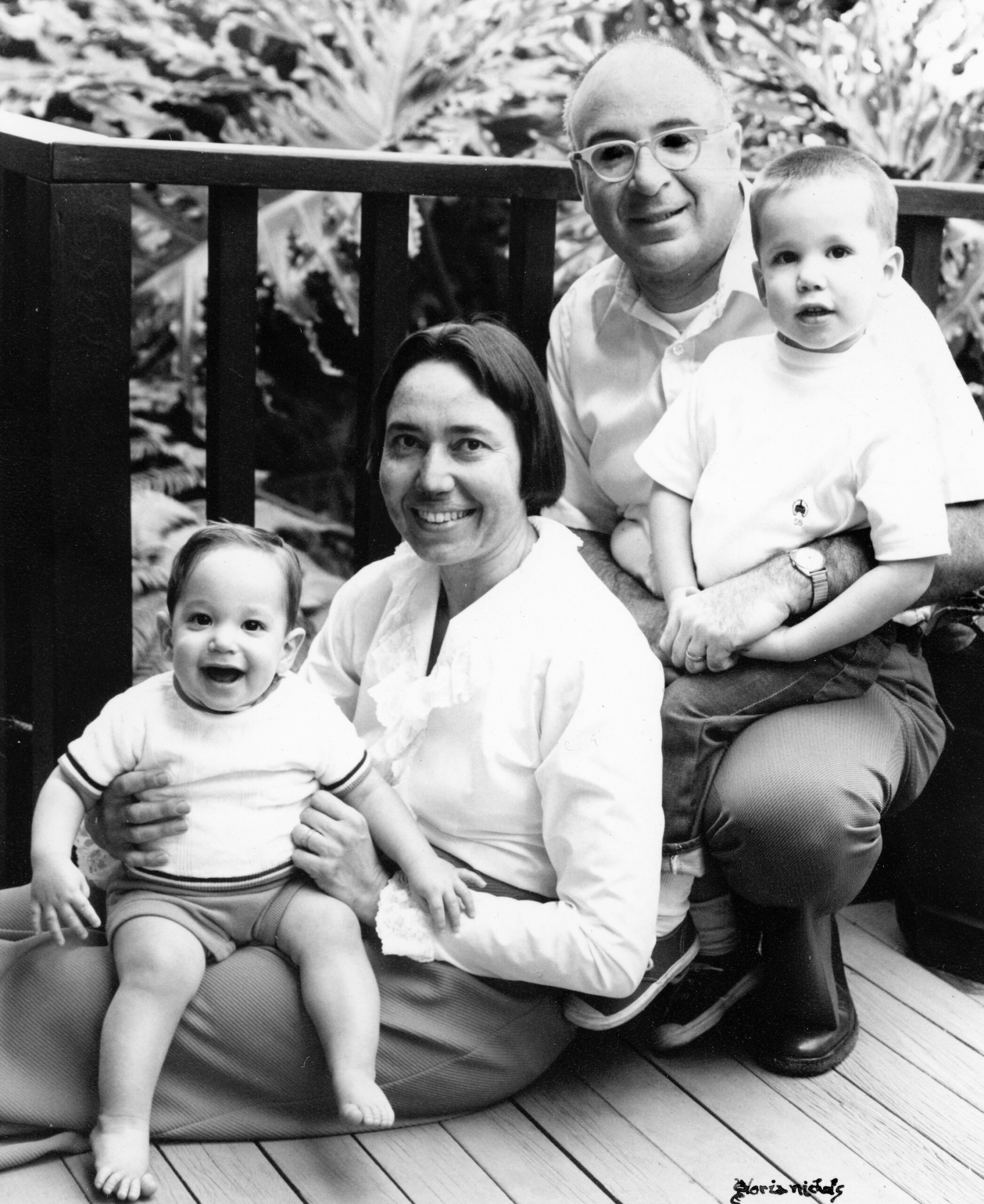

Mr. Zagar was born in Philadelphia in 1939, grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y., and received a bachelor of fine arts degree in painting and graphics at the Pratt Institute of Art in New York. He met his wife, artist Julia Zagar, in 1963. The couple married the same year and moved to South Philadelphia in 1968 after serving in the Peace Corps in Peru. Together, they founded Eye’s Gallery at 402 South St., focusing on Latin American folk art.

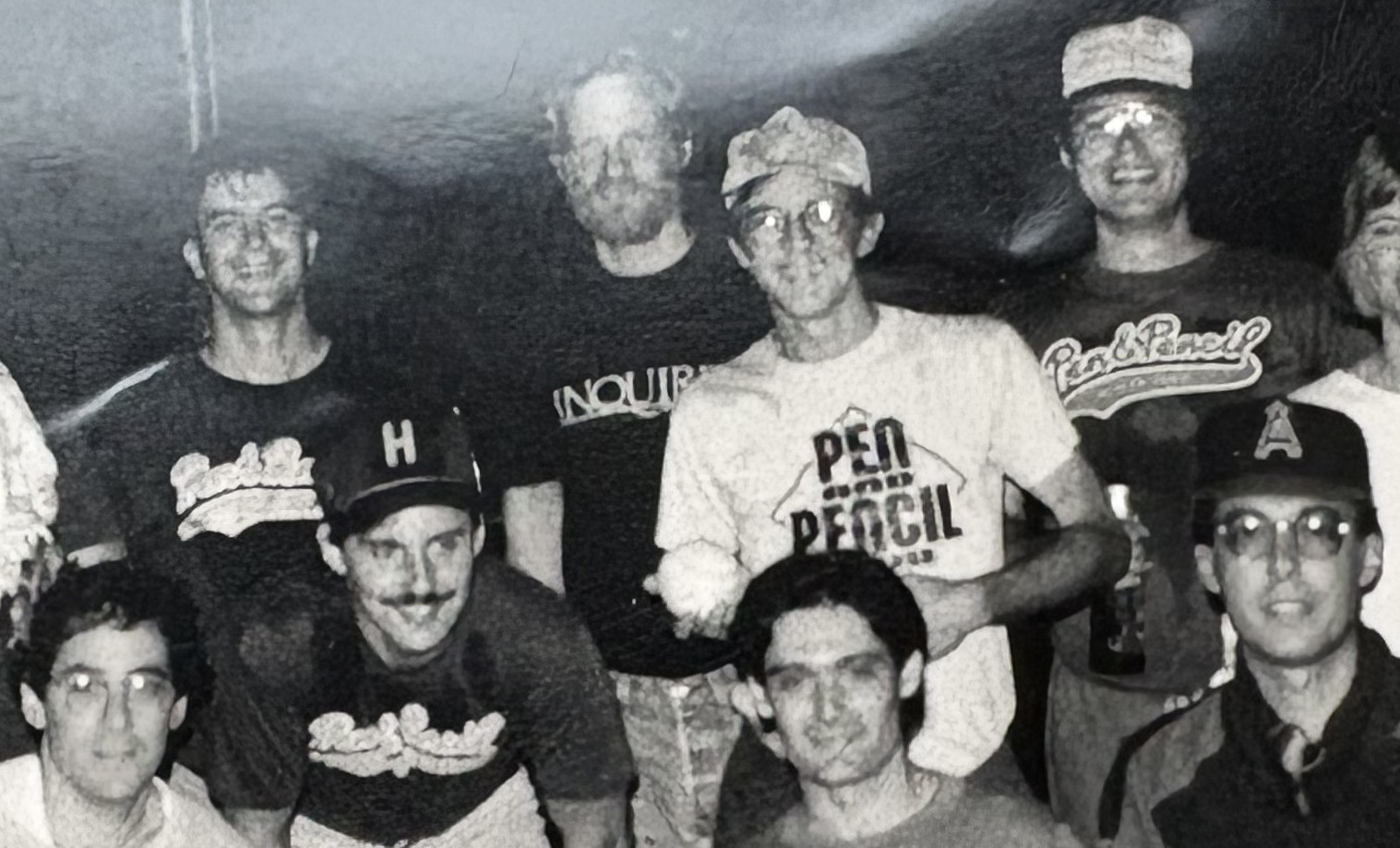

In the 1970s, the Zagars were part of a group of artists, activists, and business owners who pushed back against development of a Crosstown Expressway that would have demolished South Street. Their contributions helped lead to a neighborhood revitalization later called the South Street Renaissance.

“Philadelphia’s iconic South Street area has become inseparable from Isaiah Zagar’s singular artistic vision,” said Val Gay, chief cultural officer and executive director of Creative Philadelphia, the city’s arts office. “His mosaics redefine the very framework of the public space they inhabit. Isaiah Zagar reshaped the visual identity of Philadelphia, and his legacy will endure through all that he transformed.”

A self-taught mosaicist, Mr. Zagar used broken bottles, handmade tiles, mirrors, and other found objects to cover walls across the city, particularly in South Philly. The artist, who struggled with mental health over many years, found that creating mosaics was a therapeutic practice. He was inspired by artists Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, Kurt Schwitters, and Antonio Gaudí.

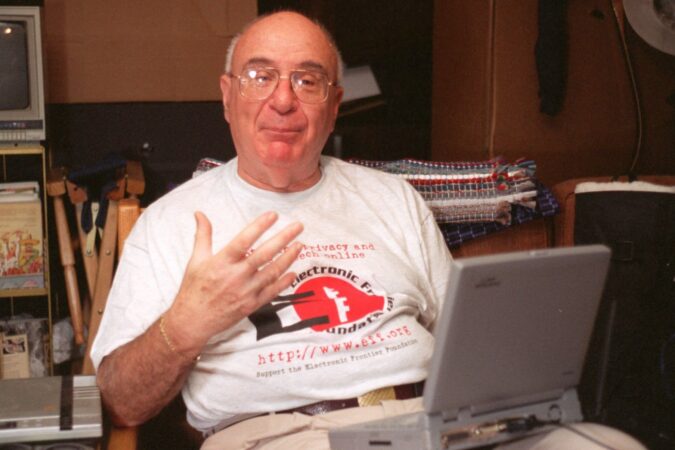

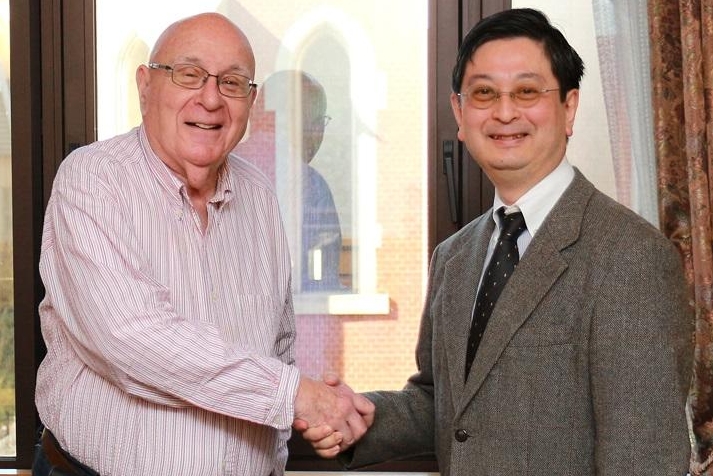

“He worked with found objects that he found everywhere and put them to use. So, [he thought], ‘Why is the thing a piece of trash? Well, it doesn’t have to be a piece of trash. It could be a piece of art, too, and still be a piece of trash,’” said longtime friend Rick Snyderman, 89, a renowned Philadelphia gallerist based in Old City. An object “in the hands of the right person changes your perspective about it. That’s, I think, what the greatest gift of Isaiah was — to change your perspective.”

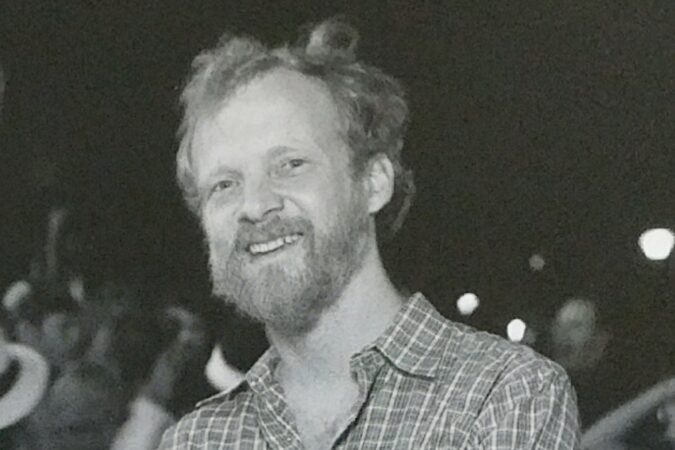

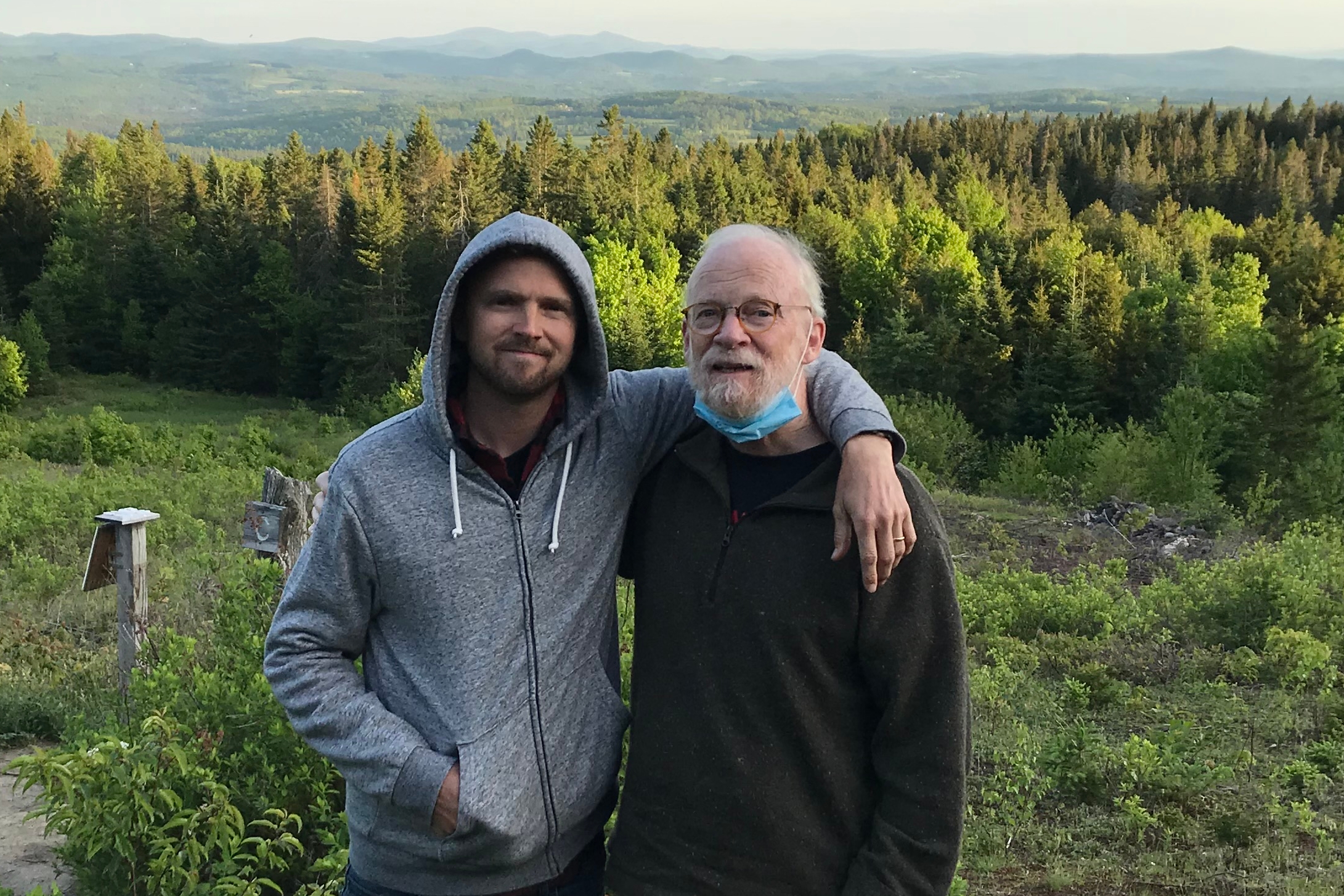

Mr. Zagar’s son, the filmmaker Jeremiah Zagar, documented his father’s life in a 2008 documentary, In a Dream. Jeremiah Zagar recently directed episodes of the HBO miniseries Task. His father came to the show’s New York City premiere last September carrying a mosaicked cane.

Snyderman remembers Mr. Zagar as a big reader and world traveler who was “eternally curious” and created artwork to make people smile. They first met in the 1960s and their families were part of the South Street community of “creative thinkers” who bonded “because they were misfits in some other world, perhaps.”

“He was a man who just didn’t pay attention to his own world, he paid attention to the larger world. One of his favorite sayings was that ‘Philadelphia is the center of the art world, and art is the center of the real world,’” Snyderman said.

More than 200 of Mr. Zagar’s mosaics adorn public walls from California and Hawaii to Mexico and Chile. His artwork is in the permanent collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, among other museums, and has been shown in solo exhibitions at cultural institutions including Washington’s Hinckley Pottery Gallery and New York’s Kornblee Gallery.

“Isaiah Zagar was devoted to mosaic work and the creation of immersive art environments. Internationally recognized, he is proudly claimed by Philadelphia as our own,” said Elisabeth Agro, the Nancy M. McNeil curator of modern and contemporary craft and decorative arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “Although his death is a profound loss to our city’s culture and creative economy, Zagar’s indelible imprint remains inextricably linked to Philadelphia’s soul.”

Synonymous with Philadelphia’s public art

Mr. Zagar’s colorful and eclectic mosaic murals have become synonymous with Philadelphia’s public art scene.

After arriving in the city, Mr. Zagar soon set about modifying Eye’s Gallery, which was then also his home. The building, the Daily News reported in 1975, was dilapidated when he took possession of it, and at one point lacked plumbing and had a wood-burning stove.

Several years into his ownership, the Daily News wrote, Mr. Zagar had evolved the rowhouse into a “womb-like living space with undulating cement walls.” Materials for its decoration were largely scavenged, and included thousands of pieces of broken glass and mirrors.

Changes, the People Paper reported, started with the cementing of a stairway wall that had become wet. Lacking experience in carpentry, plastering, and home repairs, Mr. Zagar said, he and a fellow artist cemented the wall to hide the leak, and covered it in mirrors to disguise the issue. That didn’t fix the leak, but it did inspire a kind of operating logic for his home repairs.

“We would do something artistic to hide a fault, then have to correct the fault to save the artwork,” Mr. Zagar said in 1975.

His process included embedding everything from broken teapots and cups to plates and crystal into the cement while it was still wet. Mirrors, however, were an early favorite of Mr. Zagar’s.

That idea, he told the Daily News, came from Woodstock, N.Y.-based artist Clarence Schmidt, who covered the outside of his home in broken mirrors embedded in tar.

“Mirrors intercept space, they keep poking holes in things,” Mr. Zagar said. “If they’re in the sun, they throw prisms around. You can’t fashion a mirror into an anatomical human being. It freed me from the concept of what things were supposed to look like.”

Preservation challenges

New development in Philadelphia in recent decades has led to the demolition of many of Mr. Zagar’s mosaic murals, most of which have been on private property.

By the turn of the century, Mr. Zagar had covered about 30 buildings in the city — largely then in Old City and on South Street — in his distinctive mosaic work, according to reports from the time. Among his largest passions in that medium, he told The Inquirer in 1991, were the colorful mirror and tile murals that today dot the city.

“These materials have a lasting quality,” he said at the time. “I have never seen an ugly piece of tile, it’s all beautiful.”

Mr. Zagar held grand ambitions for Philadelphia as the home of his mosaics by the mid-1990s. As he told the Daily News in 1993, he hoped to see Philly changed “into a city of the imagination.”

“My dream is [to] turn all of Philadelphia into tile city — to turn all these ugly old brick and stucco walls into a manifesto of magic,” he said.

(function() {

var l2 = function() {

new pym.Parent(‘zagar_pmg’,

‘https://media.inquirer.com/storage/inquirer/projects/innovation/arcgis_iframe/zagar_pmg.html’);

};

if (typeof(pym) === ‘undefined’) {

var h = document.getElementsByTagName(‘head’)[0],

s = document.createElement(‘script’);

s.type = ‘text/javascript’;

s.src = ‘https://pym.nprapps.org/pym.v1.min.js’;

s.onload = l2;

h.appendChild(s);

} else {

l2();

}

})();

Perhaps the prototypical example of that dream was the Painted Bride Art Center, which once was home to Mr. Zagar’s Skin of the Bride — a massive, 7,000-square-foot mosaic work that came to envelop the exterior of the building. Demolition of the Painted Bride began in December after a lengthy legal battle, but members of the Magic Gardens Preservation Team had been able to remove about 30% of the tiles for reuse in new mosaics in 2023.

Mr. Zagar’s work on the Painted Bride began in 1991 and carried on for about nine years. The work was exhausting, and his wife recalled Mr. Zagar working up to 12 hours a day for years to create what he viewed as his masterpiece.

In 1993, however, he took some creative liberties with the number of tiles, mirrors, and pieces of pottery involved with its creation.

“I’ve counted them,” he jokingly told the Daily News. “There are exactly 3,333,333.”

In summer 2022, a fire at Jim’s Steaks damaged the neighboring Eye’s Gallery, requiring lengthy restoration work that Julia Zagar spearheaded. She called the space a landmark “for the creative spirit of South Street.” The fire eventually uncovered a hidden mural by Mr. Zagar from the 1970s that had been covered up by drywall.

The Magic Gardens

In the late 1990s, Mr. Zagar expanded his sculpture and mosaic art into two empty lots neighboring his South Street home. The lots were owned by a group of Boston businessmen who had abandoned them, so with permission from the owners’ agent, Mr. Zagar cleared and transformed the space.

It would go on to become Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens, but it took a legal battle in the 2000s to keep it there.

In 2004, about a decade after Mr. Zagar started building in the space, the owners of the land ordered the artist to dismantle and remove the work ahead of plans to market the property for sale.

Mr. Zagar and a group of volunteers formed the nonprofit organization known as Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens and, with help from an anonymous benefactor, purchased the lot for $300,000, The Inquirer reported that year. The nonprofit had begun collecting donations and was tasked with raising a majority of the funding, and, if successful, the benefactor planned to donate $100,000 to the cause.

“Why it’s so important for me to save the garden is that it’s not finished,” Mr. Zagar told The Inquirer in late 2005. “The too-muchness of it is the artist’s life.”

By that time, the garden was open on a limited basis for visitors to help with fundraising efforts, and adopted a more regular schedule several years later. A swing-top trash can was placed just inside the property’s front fence to collect donations from passersby, collecting about $100 a month in its early days, The Inquirer reported.

“I make art voluminously,” Mr. Zagar told The Inquirer in 2005. “The common man is clear about it: This is art.”

The Magic Gardens has become a Philadelphia landmark, attracting about 150,000 visitors a year to walk through the immersive, labyrinthine indoor and outdoor spaces.

In 2020, after allegations of sexual harassment were leveled against Mr. Zagar, the Magic Gardens issued a statement from its board and staff reacting to concerns raised over “inappropriate past behavior.”

“Though the Gardens were originally created by Isaiah Zagar, he does not own the Gardens or have a vote on its Board of Directors,” the statement read before clarifying that the Magic Gardens operated as an independent nonprofit with its own staff and board of directors.

The allegations, the statement said, left the staff and board “hurt, angry and confused as we confronted a reality that was in every way the opposite of what we stood for.”

When asked if there was a formal investigation into Mr. Zagar’s behavior, Leah Reisman, board member of Gardens said on Friday, “Isaiah Zagar experienced mental health struggles throughout his life. While this experience often propelled his artmaking, it also at times led to challenges and repercussions in his personal and professional relationships.”

In 2020, she said, the Gardens’ staff and board “brought these concerns directly to Isaiah and assisted him in accessing professional support to address these concerns.” Mr. Zagar’s presence on site, she added, was “carefully scaffolded through the years.”

In 2023, the Zagars donated his Watkins Street Studio to Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens to open a secondary space — also entirely covered in mosaics, of course — to host arts workshops and educational programming.

Mr. Zagar’s body will be donated to the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center at Johns Hopkins University to support medical research into the degenerative condition, Snyderman said.

“Even at the end of the day, there was that contribution to people, to humanity,” he said of his friend.

Mr. Zagar is survived by his wife, Julia, and sons Jeremiah and Ezekiel Zagar.

Philadelphia’s Magic Gardens said it will announce a public memorial at a later date.

Update: Additional information has been added to this article to reflect sexual harassment allegations against Mr. Zagar.

An earlier version of the obituary misstated Mr. Zagar’s place of birth. He was born in Philadelphia.

Arts and Entertainment editor Bedatri D. Choudhury contributed to this article.