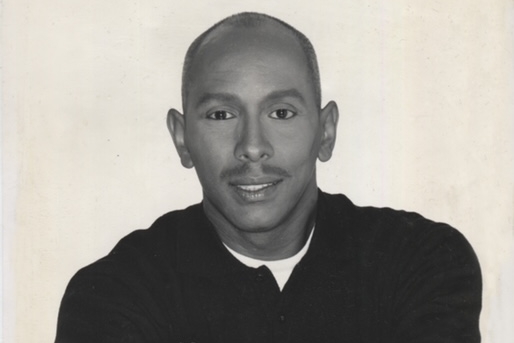

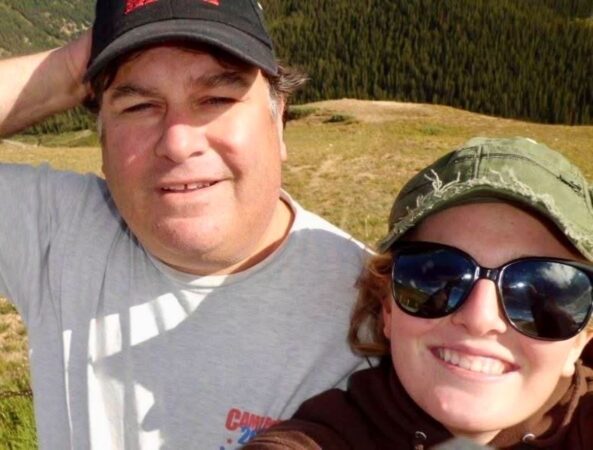

Scott Adams, who became a hero to millions of cubicle-dwelling office workers as the creator of the satirical comic strip Dilbert, only to rebrand himself as a digital provocateur — at home in the Trump era’s right-wing mediasphere — with inflammatory comments about race, politics, and identity, died Jan. 13. He was 68.

His former wife Shelly Miles Adams announced his death in a live stream Tuesday morning, reading a statement she said Mr. Adams had prepared before his death. “I had an amazing life,” the statement said in part. “I gave it everything I had.”

Mr. Adams announced in May 2025 that he had metastatic prostate cancer, with only months to live. In a YouTube live stream, he said he had tried to avoid discussing his diagnosis (“once you go public, you’re just the dying cancer guy”) but decided to speak up after President Joe Biden revealed he had the same illness.

“I’d like to extend my respect and compassion for the ex-president and his family because they’re going through an especially tough time,” he said. “It’s a terrible disease.”

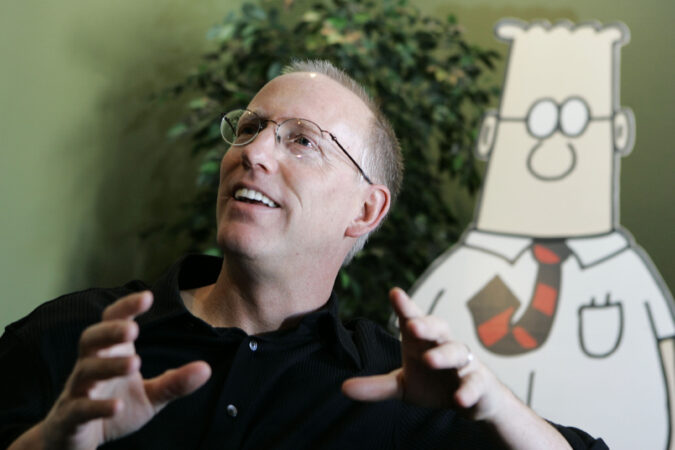

Mr. Adams was working as an engineer for the Pacific Bell telephone company when he began doodling on his cubicle whiteboard in the 1980s, dreaming of a new, more creatively fulfilling career as a cartoonist. Before long, he was amusing colleagues with his drawings of a mouthless, potato-shaped office worker: an anonymous-looking man with a bulbous nose, furrowed pate, and upturned red-and-white striped tie.

His doodles evolved into Dilbert, a syndicated comic strip that debuted in 1989 and eventually appeared in more than 2,000 newspapers around the world, rivaling Peanuts and Garfield in popularity.

Years before the film comedy Office Space and TV series The Office satirized the workplace on-screen, Dilbert poked fun at corporate jargon, managerial ineptitude, and the indignities of life in the cubicle farm.

In one strip, the title character is awarded a promotion “with no extra pay, just more responsibility,” because “it’s how we recognize our best people.” In another, he’s presented with an “employee location device” — a dog collar.

Other Dilbert cartoons could be crassly funny. Seeking to improve the company’s image, Dilbert’s pointy-haired boss hires an ad agency that uses a computer program to come up with a new “high-tech name” for the firm, using random words from astronomy and electronics. Their suggestion: “Uranus-Hertz.”

Mr. Adams proved adept at growing his audience during the tech boom of the 1990s, creating a Dilbert website long before most other cartoonists took to the internet. He also became the first major syndicated cartoonist to include his email address in his comic strip, an innovation that allowed readers to contact him directly with ideas. Their feedback convinced him to focus the cartoon entirely on the workplace, after some of the strip’s early installments explored Dilbert’s home life.

Interviewed by the Wall Street Journal in 1994, Mr. Adams observed that “the universal thread” uniting the strip’s readers “is powerlessness. Dilbert has no power over anything.”

By the end of the decade, Dilbert seemed to be everywhere, appearing on the cover of business magazines and in book-length compendiums. Mr. Adams signed off on the creation of a Dilbert Visa card and a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream flavor, branded as Totally Nuts; licensed his cartoon characters for commercials; and partnered with Seinfeld writer Larry Charles to develop an animated Dilbert television series, which aired for two seasons on the now-defunct UPN network.

Capitalizing on the cartoon’s success, he also put out a shelfful of satirical business books, beginning with the 1996 bestseller The Dilbert Principle. Inspired by the Peter Principle, a management concept in which employees are said to be promoted to their level of incompetence, Mr. Adams argued that “the most ineffective workers are systematically moved to the place where they can do the least damage: management.”

He wasn’t entirely joking. As he saw it, the people who spouted inane ideas, sucked up to management and pretended they knew more than they did were the ones who got promoted. The workplace was a mess, he suggested, but by calling out bosses’ bad behavior, Dilbert could be a force for good.

“I heard from lots of people who told me, ‘My boss started to say something that was ridiculous — management fad talk, buzzwords — but he stopped himself and said, “OK, this sounds like it came out of a Dilbert comic,’ and then started speaking in English again.’

“There is a fear of being the target of humor,” Mr. Adams told the Harvard Business Review.

Companies such as Xerox incorporated the character into communications and training programs. But some critics found the cartoon’s sarcasm more corrosive than entertaining. Author and progressive activist Norman Solomon, who wrote a book-length critique of the comic, argued that Dilbert was hardly subversive, saying that it offered more for bosses than workers.

“Dilbert does not suggest that we do much other than roll our eyes, find a suitably acid quip, and continue to smolder while avoiding deeper questions about corporate power in our society,” Solomon wrote.

Mr. Adams scoffed at the criticism, lampooning Solomon by name in his books and comic strips. “My goal is not to change the world,” he told the Associated Press in 1997. “My goal is to make a few bucks and hope you laugh in the process.”

In interviews, he was often self-deprecating, declaring that his comic strip was “poorly drawn” and noting that long before he made Dilbert he “failed at many things,” including computer games he attempted to program and sell. His other failures included the Dilberito, a line of vitamin-filled veggie wraps that ended up making people “very gassy,” and his short-lived attempt at managing an unprofitable restaurant, Stacey’s at Waterford, that he owned in the Bay Area.

“Certainly I’m an example of the Dilbert Principle,” he told the New York Times in 2007, a few months into his stint as a restaurant boss. “I can’t cook. I can’t remember customers’ orders. I can’t do most of the jobs I pay people to do.” (Employees told the newspaper that Mr. Adams was loyal and kind, yet totally clueless. “I’ve been in this business 23 years, and I’ve seen a lot of things,” the head chef said. “He truly has no idea what he’s doing.”)

On the side, Mr. Adams blogged about fitness, politics, and the art of seduction — drawing, he said, on his training as a certified hypnotist, which he learned before becoming a cartoonist. He also wrote about his struggles with focal dystonia, a neurological disorder, which caused spasms in his pinkie finger that made it difficult to draw. Mr. Adams said he developed tricks to get around the issue, holding his pen or pencil to the paper for just a few seconds at a time, and underwent experimental surgery to treat a related condition, spasmodic dysphonia, that hindered his ability to speak.

Politically, he cast himself as an independent, saying he didn’t vote and was not a member of any party. But he also veered into far-right political terrain on his blog, including in a 2006 post in which he questioned “how the Holocaust death total of 6 million was determined.” A few years later, writing about “men’s rights,” he compared society’s treatment of women to its treatment of children and people with mental disabilities.

“You don’t argue with a 4-year old about why he shouldn’t eat candy for dinner. You don’t punch a mentally handicapped guy even if he punches you first. And you don’t argue when a woman tells you she’s only making 80 cents to your dollar. It’s the path of least resistance,” he wrote.

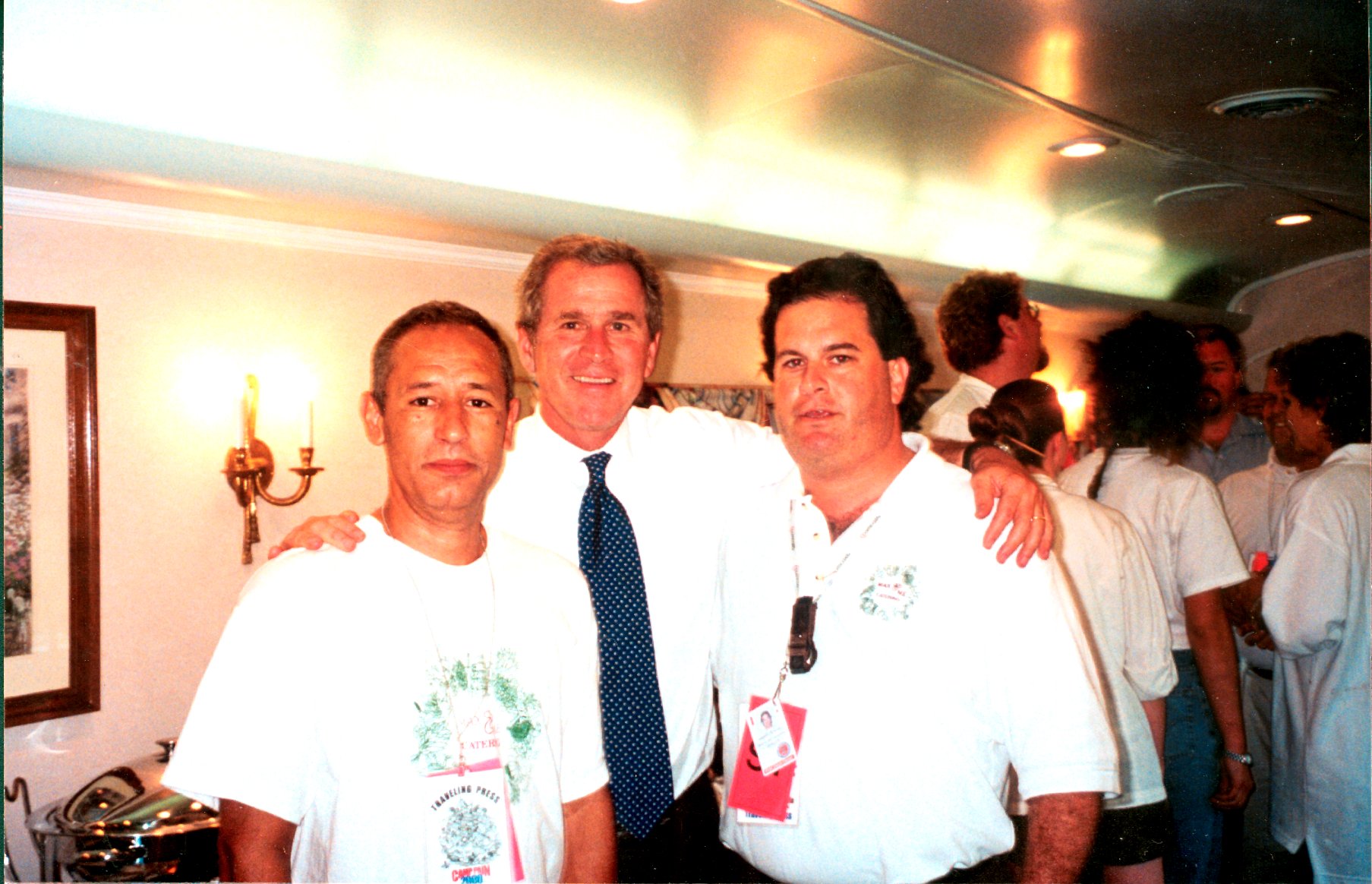

Mr. Adams made headlines with his prediction that Donald Trump, whom he considered a master of persuasion, would win the 2016 presidential election. He was later invited to the White House after publishing the 2017 nonfiction book Win Bigly: Persuasion in a World Where Facts Don’t Matter. (The book’s cover art featured an orange-hued drawing of Dogbert, Dilbert’s megalomaniacal pet dog, with a Trumplike swoosh of hair.)

“He was a fantastic guy, who liked and respected me when it wasn’t fashionable to do so,” Trump said Tuesday in a Truth Social post, referring to Mr. Adams as “the Great Influencer.” “My condolences go out to his family, and all of his many friends and listeners.”

Amid a national reckoning on race in the 2020s, Mr. Adams sparked a backlash for his criticisms of diversity, equity, and inclusion programs, and for social media posts in which he joked that he was “going to self-identify as a Black woman” after President Joe Biden vowed to nominate an African American woman to the Supreme Court. In 2022, he introduced Dilbert’s first Black character, an engineer named Dave who announces to colleagues that he identifies “as white,” ruining management’s plan to “add some diversity to the engineering team.”

The following year, Dilbert was dropped by hundreds of newspapers, including The Philadelphia Inquirer and Daily News, after Mr. Adams delivered a rant that was widely decried as hateful and racist. Appearing on his YouTube live-stream show, Real Coffee With Scott Adams, he discussed a controversial Rasmussen poll asking people if they agreed with the statement “It’s OK to be white,” a slogan associated with the white supremacist movement. About a quarter of Black respondents said “no.”

Mr. Adams was appalled by the results. He declared that African Americans were “a hate group,” adding: “I don’t want to have anything to do with them. And I would say, based on the current way things are going, the best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from Black people.”

Within a week his syndicate and publisher, Andrews McMeel Universal, cut ties with the cartoonist. Mr. Adams defended his comments, saying he had meant the remarks as hyperbole, and found support from conservative political activists as well as billionaire Tesla executive Elon Musk.

In a follow-up show on YouTube, he disavowed racism against “individuals” while also telling viewers that “you should absolutely be racist whenever it’s to your advantage.” Weeks later, he relaunched Dilbert on the subscription website Locals, vowing that the comic would be “spicier” — less “PC” — “than the original.”

“Only the dying leftist Fake News industry canceled me (for out-of-context news of course),” he tweeted in March 2023. “Social media and banking unaffected. Personal life improved. Never been more popular in my life.”

From bank teller to cartoonist

Scott Raymond Adams was born in Windham, N.Y., a ski town in the Catskills, on June 8, 1957. His father was a postal clerk, and his mother was a real estate agent who later worked on a speaker-factory assembly line.

Growing up, Mr. Adams copied characters out of his favorite comic strips, Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts and Russell Myers’ Broom-Hilda. He applied for a correspondence course at the Famous Artists School but was rejected, he said, because he was only 11. The minimum age was 12.

Mr. Adams eventually took a drawing course at Hartwick College in Oneonta, an hour’s drive from his hometown. He received the lowest grade in the class and decided to focus instead on economics, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1979. He moved to San Francisco, got a job as a bank teller at Crocker National Bank and, in his telling, was twice robbed at gunpoint while working behind the counter.

At night, he took business classes at the University of California at Berkeley. He earned an MBA in 1986 and joined PacBell as an applications engineer, though he found himself deeply unhappy. “About 60 percent of my job at Pacific Bell involved trying to look busy,” he wrote in a 2013 book, How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big: Kind of the Story of My Life.

After watching a public television series, Funny Business: The Art in Cartooning, he decided he had found his calling. Mr. Adams struck up a correspondence with the show’s host, cartoonist John “Jack” Cassady, who encouraged him to submit to major magazines like Playboy and the New Yorker.

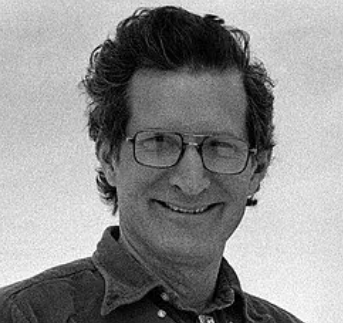

All his cartoons were rejected. But with Cassady’s encouragement, Mr. Adams continued to draw, waking up at 4 a.m. and sitting down with a cup of coffee to work on doodles of Dilbert and other characters. He stayed motivated in part by writing an affirmation: “I, Scott Adams, will become a famous cartoonist.”

Even after he signed a contract to publish Dilbert through United Feature Syndicate, Mr. Adams continued to work at his day job, making $70,000 a year and gathering ideas for his strip while sitting at cubicle No. 4S700R. He left the company in 1995, and two years later he won the National Cartoonists Society’s highest honor, the Reuben Award for cartoonist of the year.

Mr. Adams was twice married and divorced, to Shelly Miles and Kristina Basham. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Looking back on his career, Mr. Adams said he was especially proud of two novellas he had written, God’s Debris (2001) and the sequel The Religion War (2004). The latter was set in 2040 and revolved around a civilizational clash between the West and a fundamentalist Muslim society in the Middle East.

Discussing the plot in a 2017 interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, Mr. Adams said that the Muslim extremists are defeated after the hero builds a wall around them and “essentially kills everybody there.”

“I have to be careful, because I’m talking about something pretty close to genocide, so I’m not saying I prefer it, I’m saying I predict it,” he added.

The magazine reported that Mr. Adams believed the novellas, not Dilbert, would be his ultimate legacy.