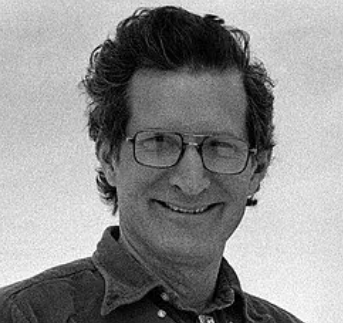

As he stands outside the Narberth Bookshop on a frigid January afternoon, it’s clear Dana Edwards has a vision.

Imagine, he says, as he sweeps his hands toward the borough’s downtown corridor, getting off the train and stopping into a small grocery for a bite to eat before heading home on foot. Maybe you buy a gift, or an ice cream cone, or a bottle of wine.

Like anywhere, Narberth “could use a little bit of revitalization here and there,” Edwards said. But you can “see the potential.”

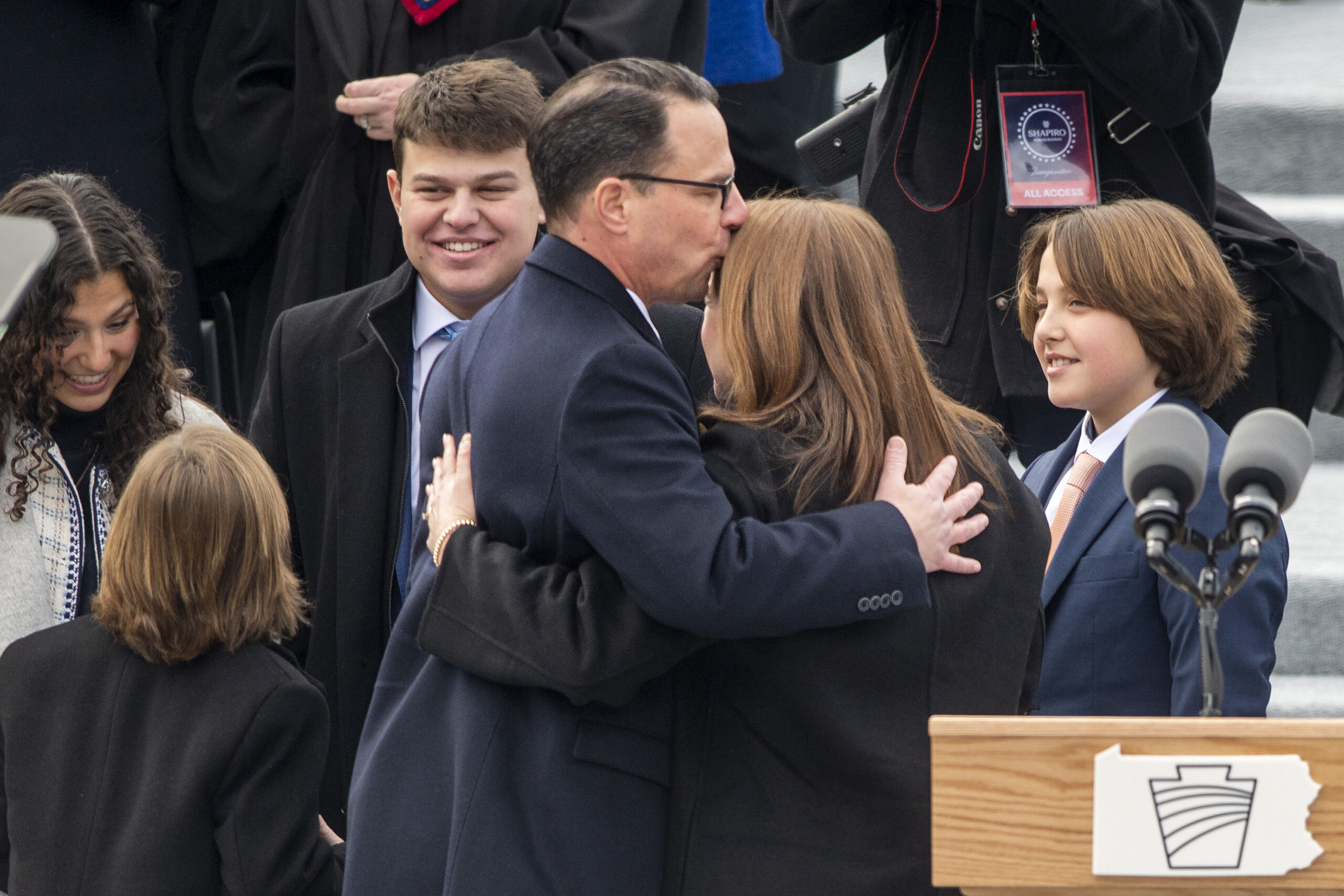

Edwards, 53, was sworn in as Narberth’s mayor earlier this month. The longtime financial technology officer moved there from Pittsburgh five years ago with his wife, Miranda. They have a 2-year-old son, and Edwards has two older children, 19 and 22, from his first marriage. Edwards had never run for office before, but after falling in love with the borough (and being encouraged by neighbors), he stepped into the public eye last year. He won the local Democratic Party’s endorsement, then ran unopposed in the primary and general election. This month, Edwards replaced Andrea Deutsch, who had served as Narberth’s mayor since 2017.

As the 0.5-square-mile, 4,500-person borough faces infrastructure challenges and debates over development, Edwards says he is ready to steer Narberth in the right direction through communication, thoughtful growth, and a social media presence he calls “purposely cringey and fun.”

From San Juan to Narberth, with stops in between

Edwards grew up in San Juan, Puerto Rico. There, Edwards says, he saw power outages, infrastructure issues, and food shortages. It was a formative experience that taught him about the collective — what it means to come together in the face of persistent challenges.

He earned a degree in chemistry in 1994 from the College of Charleston in South Carolina. Though the goal was to become a doctor, Edwards was drawn to technology. He went back to school, and in 1997 earned a degree in computer science, also from the College of Charleston. Edwards has a master’s in business administration from Queens University of Charlotte in North Carolina.

Edwards has spent three decades in the world of information technology, working mostly for major banks. He was the chief technology officer of the Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, then for PNC Bank. He is now the group chief technology officer for Simply Business, a London-based online insurance broker. He has lived in Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Los Angeles, Pittsburgh, and now Narberth. He has over 18,000 followers on LinkedIn.

By his own admission, Edwards’ civic background is “a little bit light.” He has given to various causes over the years, and said he was involved in the ACLU in the early 2000s. He helped organize Narberth’s first Pride in the Park event in 2022 and said he has joined the Main Line NAACP chapter.

Polarization happening ‘in our little town’

Edwards started thinking about running for office “when the national scene changed dramatically.”

He described beginning to sense a deep polarization both between and within America’s political parties.

“I felt like I saw it happening locally. I saw it happening in our little town,” he said.

As the mayoral race approached, neighbors began telling Edwards he had the right “thing” to run. He could build a strategic plan, lead an organization, and understand financials. At a candidate forum last year, Edwards said he originally planned to run for mayor in 2029, but decided to move his campaign up to 2025.

Edwards earned the backing of Narberth’s Democratic committee people last April, beating out attorney Rebecca Starr in a heated endorsement process.

During a March 2025 meeting, local Democrats squabbled over whether or not to endorse a candidate, citing “animosity” in the race (candidates are discouraged from running as Democrats if they do not receive the endorsement of the local committee). The committee ultimately voted to make an endorsement, which went to Edwards.

After the meeting, Starr withdrew from the race, citing “vitriol” in the campaign.

“I think [in] any good race, at some point, you have to have more than one candidate. Because otherwise, people are just getting selected, not elected,” Edwards said, referencing the endorsement process. “I do think that she would be a great candidate also, and I hope she runs again.”

Edwards believes the community has largely moved on from any division that colored the primary. Really, he added, it’s more important to get people talking about the issues the mayor can solve — streets, garbage pickup, infrastructure.

“I’m just really focused on Narberth,” he said.

Building a ‘community-oriented’ future

Edwards says he is committed to sustainable growth in a borough whose residents have diverse, and sometimes competing, visions for its future.

There are two extremes, Edwards says. On one end, the borough could leave everything as it is. The buildings might fall apart, but they would be the same buildings that everyone knows and loves. On the other end, there is rapid growth, like bringing a Walmart Supercenter to Haverford Avenue.

“It’s that thing in the middle that we’re looking for,” he said — a “hometown feel” with “community-oriented” businesses.

Edwards is eager to get the 230 Haverford Ave. development across the finish line. The long-awaited project plans to bring 25 new apartment units and ground-floor retail to Narberth’s commercial core. The project, helmed by local real estate developer Tim Rubin, has been in the works for over five years, but faced pandemic-era setbacks that have left a number of vacant storefronts downtown.

The mayor is also focused on the Narberth Avenue Bridge, a century-old span and main artery that has been closed for several years due to safety concerns and subsequent construction. Road-Con, the contractor updating the bridge, anticipates it will be completed by summer 2029.

Edwards plans to write a regular newsletter, hold town halls, and host coffee chats. He hopes to put together an unofficial advisory group to bring together people, and opinions, from across the small borough.

Edwards believes “the DNA of Narberth is alive and kicking,” from the Dickens Festival to the Narberth Outsiders baseball team. To keep it alive, though, the borough needs to bring business in and remind people why they love to live, shop, and work in Narberth.

“It’s all about relationships and commerce,” he said. “[That] is going to be what brings us together.”

This suburban content is produced with support from the Leslie Miller and Richard Worley Foundation and The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Editorial content is created independently of the project donors. Gifts to support The Inquirer’s high-impact journalism can be made at inquirer.com/donate. A list of Lenfest Institute donors can be found at lenfestinstitute.org/supporters.