Pennsylvania’s race for governor has officially begun. And 10 months before the election, the November matchup already appears to be set.

Democratic Gov. Josh Shapiro formally announced his reelection campaign Thursday — not that anyone thought he wouldn’t run. And Republicans have rapidly coalesced behind the state party’s endorsed candidate, Pennsylvania Treasurer Stacy Garrity.

The race will dominate Pennsylvania politics through November, but it could also have a national impact as Democrats hope Shapiro at the top of the state ticket can elevate the party’s chances in several key congressional races.

Here’s what you need to know about the high-stakes contest.

The candidates

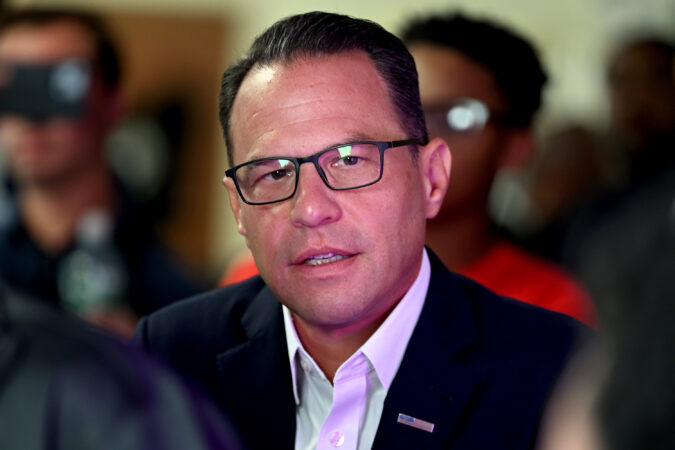

Josh Shapiro

Shapiro is seeking a second term as Pennsylvania’s top executive as he’s rumored to be setting his sights on the presidency in 2028. Just weeks after his campaign launch, Shapiro will head to New York and Washington, D.C., as part of a multicity book tour promoting his memoir.

Shapiro was first elected to public office in 2004 when he flipped a state House seat to represent parts of Montgomery County. As a freshman lawmaker, he quickly built a reputation of brokering deals across party lines. He went on to win a seat on the Montgomery County Board of Commissioners in 2011, flipping the board blue for the first time in decades.

Shapiro was elected state attorney general in 2016, a year when Pennsylvania went for Republican Donald Trump in the presidential contest. The position put Shapiro in the national spotlight in 2020 when Trump sought to overturn his loss in the state that year through a series of legal challenges, which Shapiro’s office successfully battled in court.

He went on to decisively beat Trump-backed Republican State. Sen. Doug Mastriano for the governorship in 2022. Despite an endorsement from Trump, Mastriano lacked the support of much of Pennsylvania’s Republican establishment and spent the election cycle discouraging his supporters from voting by mail.

Throughout Shapiro’s first term as governor, he has highlighted his bipartisan bona fides and ability to “get stuff done” — his campaign motto — despite contending with a divided legislature. His launch video highlights the quick reconstruction of I-95 following a tanker explosion in 2023.

In 2024, Shapiro was vetted as a possible running mate for then-Vice President Kamala Harris, who ultimately snubbed the Pennsylvanian in favor of Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz. Harris went on to lose the state to Trump.

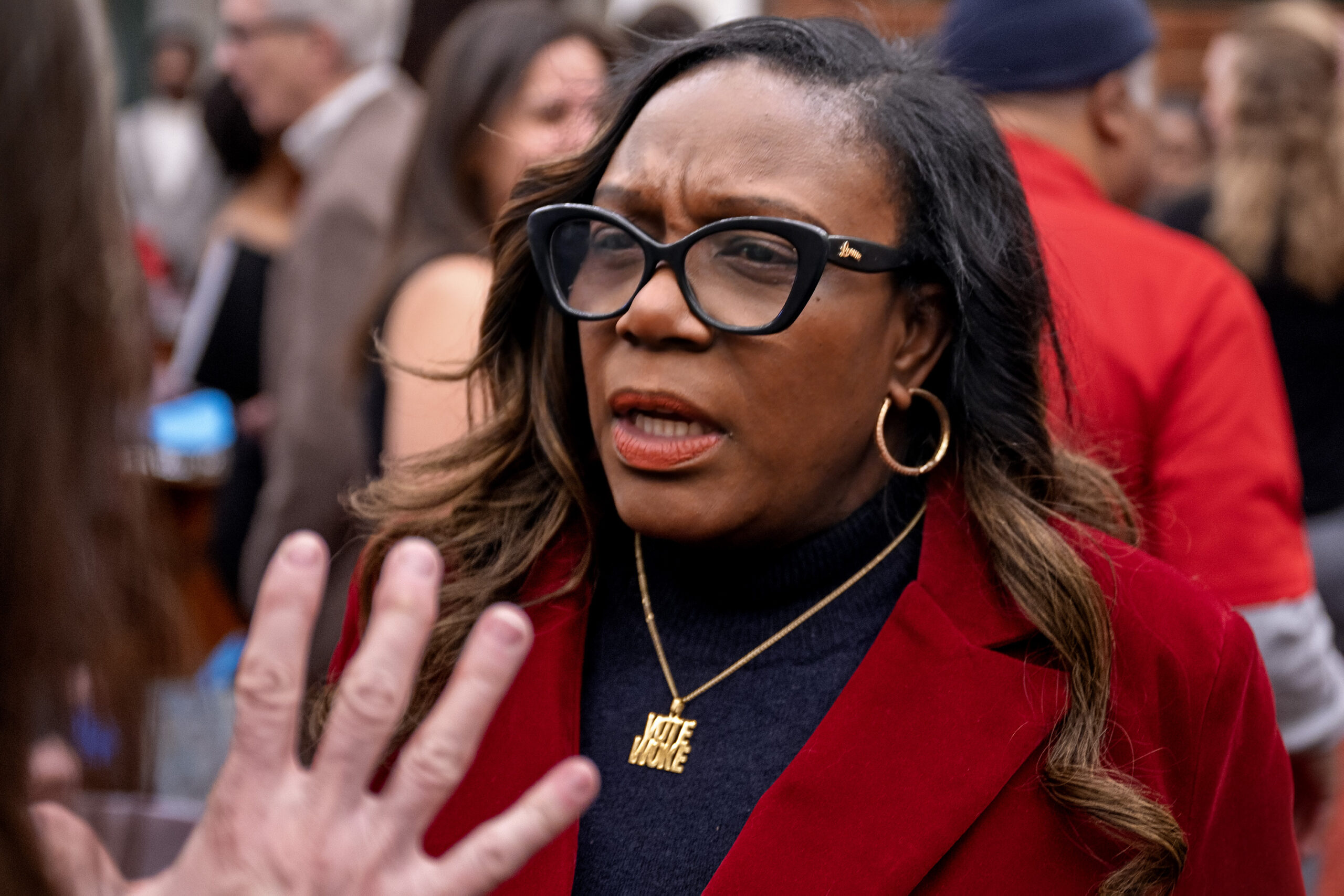

Stacy Garrity

Garrity is Shapiro’s likely opponent in the general election. She earned an early endorsement from the Pennsylvania Republican Party in September after winning a second term to her current position in 2024 with the highest total of votes in history for a state office, breaking a record previously held by Shapiro.

She has been quick to go on the attack against the Democratic governor in recent months. Throughout Pennsylvania’s monthslong budget impasse Garrity criticized Shapiro’s leadership style and panned the final agreement he reached with lawmakers as fiscally irresponsible.

Garrity’s campaign has focused on contrasting her priorities with Shapiro’s, arguing the governor is more interested in higher office than he is in Pennsylvania.

A strong supporter of Trump, Garrity is one of the only women that has been elected to statewide office in Pennsylvania history. If elected, she would be the first female governor in state history.

Garrity is a retired U.S. Army colonel who was executive at Global Tungsten & Powders Corp. before she was elected treasurer in 2020. Running a relatively low-key state office, Garrity successfully lobbied Pennsylvania’s General Assembly to allow her to issue checks to residents whose unclaimed property was held by her office, even if they hadn’t filed claims requesting it.

Anyone else?

While Shapiro and Garrity are the likely nominees for their parties, candidates have until March to file petitions for the race. That theoretically leaves the possibility of a primary contest open for both candidates, but it appears unlikely at this point.

Mastriano, who ran against Shapiro in 2022, spent months floating a potential run for governor against Garrity. He announced Wednesday that he would not be seeking the Republican nomination.

The stakes

Why this matters for Pennsylvanians

The outcome of Pennsylvania’s gubernatorial race could hold wide-ranging impacts on transportation funding, election law, and education policy, among other issues.

The state’s governor has a powerful role in issuing executing actions, setting agendas for the General Assembly, and signing or vetoing new laws. The governor also appoints the secretary of state, the top Pennsylvania election official who will oversee the administration of the next presidential election in the key swing state.

Throughout the entirety of Shapiro’s first term, he has been forced to work across the aisle because of the split legislature. Throughout that time the balance of power in Harrisburg has tilted toward Democrats who hold the governor’s mansion and the Pennsylvania House. But many of the party’s goals — including expanded funding for SEPTA and other public transit — have been blocked by the Republican-held Senate.

If Garrity were to win that dynamic would shift, offering Republicans more leverage as they seek to cut state spending and expand school voucher options (while Shapiro has said he supports vouchers, the policy has not made it into any budget deals under him).

Shapiro’s ambition

Widely rumored to have his sights set on higher office, Shapiro’s presidential ambitions may rise and fall with his performance in his reelection campaign.

Shapiro coasted to victory against Mastriano in 2022, winning by 15 points. The 2026 election is expected to be good for Democrats with Trump becoming an increasingly unpopular president.

But Garrity is viewed as a potentially stronger opponent to take on Shapiro than Mastriano, even though her political views have often aligned with the far-right senator.

When the midterms conclude, the 2028 presidential cycle will begin. If Shapiro can pull off another decisive win in a state that voted for Trump in 2024, it could go a long way toward aiding his national profile. But if Garrity wins, it could end the governor’s chances of putting up a serious campaign for the presidency in 2028.

Every other race in Pennsylvania

The governor’s contest is the marquee race in Pennsylvania in 2026. Garrity and Shapiro have the ability to help or hurt candidates running for Pennsylvania’s statehouse and Congress.

The momentum of these candidates, and their ability to draw voters to the polls could play a key role in determining whether Democrats can successfully flip four competitive U.S. House districts as they attempt to take back the chamber.

Democrats also narrowly hold control of the Pennsylvania House and are hoping to flip three seats to regain control of the Pennsylvania Senate for the first time in decades. If Democrats successfully flip the state Senate blue, it would offer Shapiro a Democratic trifecta to push for long-held Democratic goals if he were to win reelection.

Strong Democratic turnout at the statewide level could drive enthusiasm down-ballot, and vice versa. Similarly, weak turnout could aid Republican incumbents in retaining their seats.

The dates

The election is still months away but here are days Pennsylvanians should put on their calendars.

- May 4: Voter registration deadline for the primary election.

- May 19: Primary election.

- Oct. 19: Voter registration deadline for the general election.

- Nov. 3: General election.