Philadelphia is on track to record the lowest number of fatal overdoses in nearly a decade in 2025, according to preliminary state data.

State officials reported 747 overdose deaths in the city as of Dec. 23. The city last recorded fewer than 1,000 deaths in 2016, when 907 people died of overdoses.

The dramatic decline mirrors national trends in overdose deaths, which peaked during the COVID-19 pandemic and have since been steadily falling.

window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r,i=0;r=e[i];i++)if(r.contentWindow===a.source){var d=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][t]+”px”;r.style.height=d}}});

Likewise, overdose deaths are dropping in Pennsylvania, with a 29% decline in deaths reported statewide between 2023 and 2024, according to preliminary data from the state.

Preliminary data for 2025 indicate that deaths are also on track to decline again across the state, with 2,178 overdoses reported as of Dec. 23, according to state data. In all of 2024, the state recorded 3,340 overdose deaths.

window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var e=document.querySelectorAll(“iframe”);for(var t in a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var r,i=0;r=e[i];i++)if(r.contentWindow===a.source){var d=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][t]+”px”;r.style.height=d}}});

City officials in Philadelphia said there are slight differences in how the state and the city report overdose data and could not comment extensively on the state figures. But the city’s own data also show dramatic drops in deaths in the last several years.

As recently as 2022, deaths in the city had soared to their highest-ever rate. But they decreased slightly in 2023.

Citing preliminary data from 2024, Philly Stat 360, a city-run database that tracks quality-of-life metrics, reported 1,064 overdose deaths — a 19% decrease in fatal overdoses from the year before. The city has not yet released its own statistics for 2025.

“My first reaction to hearing these numbers is absolute joy,” said Keli McLoyd, the director of the Philadelphia Overdose Response Unit (ORU). “With that said, the number should be zero. Every overdose is preventable. Every single one of those lives lost is a person.”

State officials said their work to expand overdose prevention efforts and ease entry to treatment has contributed to the dramatic drops in deaths. Still, they said, there is more work to be done.

“Even with the overall decreases, we are still losing too many people — mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, grandparents, grandchildren — to overdose,” said Stephany Dugan, a spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs.

She added that all Pennsylvanians “deserve equal and equitable access” to addiction treatment.

Decreases in overdoses in Philadelphia

Discerning the cause of the dramatic drops in overdose deaths can be difficult, city officials say.

“We have to acknowledge that it’s a huge, huge change, and so we really are hopefully doing something right. But I think it’s going to be very hard, if not impossible, to say that one thing resulted in this massive reduction in fatal overdose deaths,” McLoyd said.

Still, efforts at the state and local levels to increase access to naloxone, the overdose-reversing drug, likely made a difference, she said.

A number of local advocates in the addiction medicine field have speculated that there is still much to learn about how the COVID-19 pandemic affected overdose rates, said Daniel Teixeira da Silva, the director of the Division of Substance Use Prevention and Harm Reduction at the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

“When we look at the [overdose] increases after 2016, leading up to COVID, we can tie that to the introduction of fentanyl to the [drug] supply,” he said Monday, referring to the synthetic opioid behind most of the city’s fatal overdoses.

“When you look at the increases from 2020 to 2022 — this is where I just don’t think we know enough yet. It’s hard to say COVID didn’t impact [deaths]. We look at what was going on at the time, contributors to more risky substance use such as people losing employment, the isolation,” Teixeira da Silva said.

Likewise, he said, policy changes that came about during the pandemic, such as easing some restrictions around opioid addiction medications, could be contributing to a drop in deaths now.

“Maybe we’re seeing benefits of the policies enacted during COVID,” he said.

A changing drug landscape

On Philly Stat 360, city officials said fentanyl still drives nearly all of the opioid overdose deaths in the city.

But about 70% of deaths involved a stimulant like cocaine or methamphetamine in 2024. And about half of the city’s fatal overdoses that year involved both stimulants and opioids.

Taking stock of the drop in overdose deaths, city officials noted the success of a 2024 program at the ORU to deliver naloxone, the opioid overdose-reversing drug sold under the brand name Narcan, to households in neighborhoods seeing a high number of overdoses.

They included neighborhoods in North Philadelphia, where overdose deaths had risen over the last several years. Across the city, Black and Hispanic communities had seen high rises in overdoses — but neighbors often reported receiving fewer resources to address them.

Workers assigned to the naloxone initiative knocked on 100,000 doors offering the medication and access to addiction treatment. In some neighborhoods, up to 88% of neighbors who answered their doors accepted some kind of resource from staffers, according to a city report on the program. McLoyd also helmed an effort to ensure all city fire stations had naloxone on hand.

“We’re sharing those messages that this is a tool for everyone, not just people who use drugs or people who love those who use drugs,” since some people may hide their addiction from others, she said.

This year, the city launched another campaign to educate residents about the risk of heart disease from stimulant use. Eighty percent of overdose deaths among Black Philadelphians in 2023 involved a stimulant, and about half of the Black Philadelphians who died of an overdose between 2019 and 2022 had a history of cardiovascular disease.

“We see opioid-stimulant [overdose deaths] decreasing, but stimulant-only [overdoses] being really persistent,” Teixeira da Silva said. “Stimulant overdoses are not reversed by Narcan,” so it is important to help vulnerable residents understand the specific harms caused by stimulants.

As overdoses decrease in the general population, McLoyd said, it is crucial to maintain outreach efforts toward groups that have seen rising overdoses in recent years, like pregnant people and teens in the juvenile justice system.

“Within certain populations, overdoses are still disproportionately high. We want to develop programs that speak specifically to those populations,” she said.

City officials have also hailed the Riverview Wellness Center, a 234-bed recovery home that offers supportive services to people who have completed a 30-day stay in inpatient treatment.

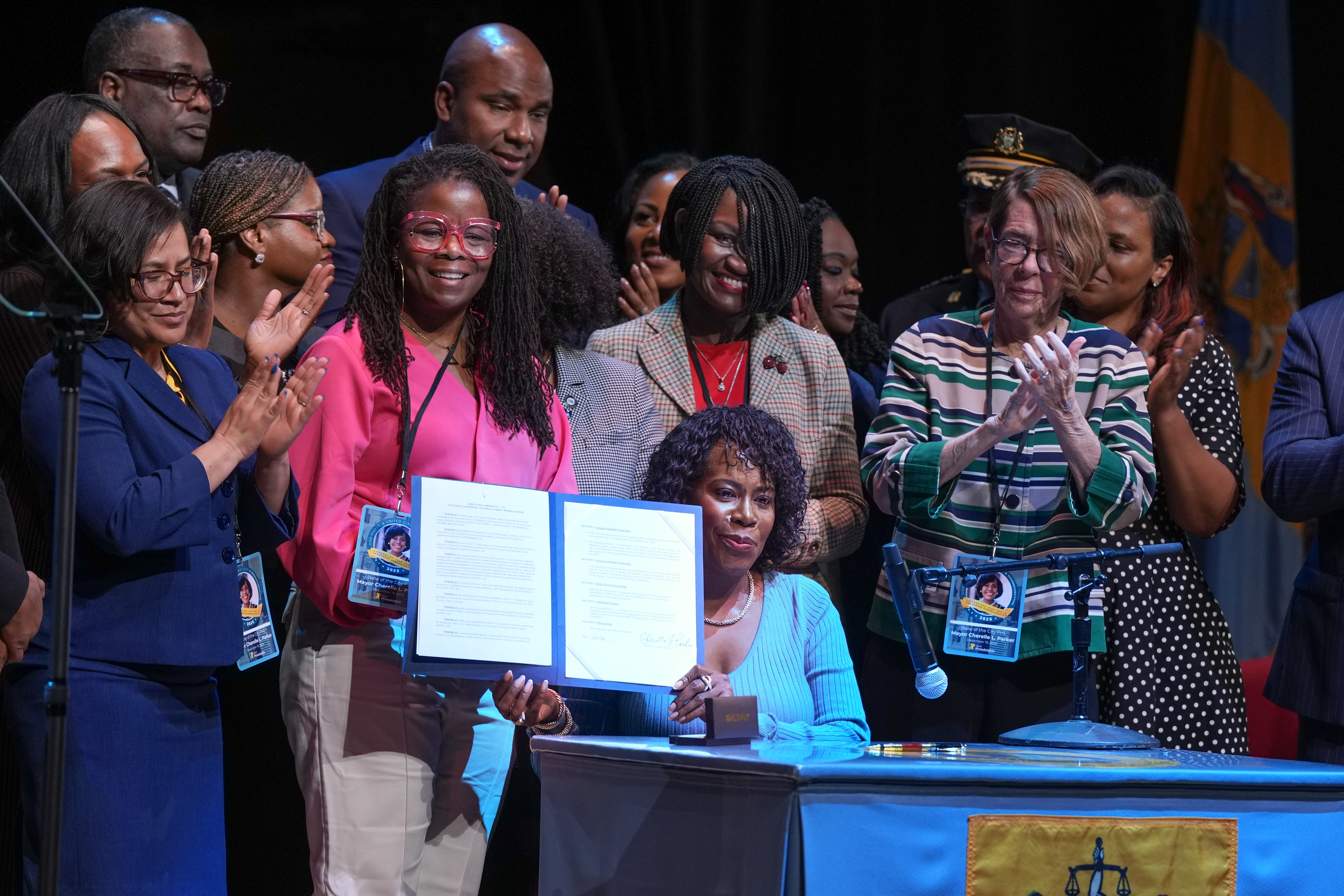

But Mayor Cherelle L. Parker’s administration has faced criticism from advocates for people in addiction over her decision last year to slash funding for syringe exchanges. Critics have also decried City Council legislation that regulates mobile medical services for people with addiction, requiring permits to offer care and limiting operating hours and locations in some neighborhoods.

Teixeira da Silva said that the city is using the legislation to more effectively coordinate care for people with addiction. He said his division has been involved in the new permitting process for mobile services to “get them approved as fast as possible to ensure there isn’t a gap in access.”

Statewide initiatives

Across Pennsylvania, the state’s Overdose Prevention Program handed out more than 415,000 doses of naloxone in the first six months of 2025, said Dugan, the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs spokesperson.

Those doses helped reverse more than 6,100 overdoses, Dugan said earlier this month.

The state also distributed 437,000 test strips to help drug users detect fentanyl and xylazine. The animal tranquilizer contaminated much of Philadelphia’s illicit opioid supply starting at the beginning of the decade and can cause severe skin wounds that sometimes lead to amputation.

Authorities credited efforts to increase access to treatment in rural counties and to decrease wait times for addiction treatment, implementing a “warm handoff” program that allows patients to transfer directly from hospitals to addiction treatment.

More than 22,000 Pennsylvanians were offered addiction treatment from hospitals in the first 10 months of 2025. Nearly 60% of people who received referrals accepted them, state officials said.

Advocates say that the state’s focus on programs to prevent overdoses has paid off.

“I’m really impressed and grateful for the state and their investment in harm-reduction programs,” said Sarah Laurel, who heads the Philadelphia-based addiction outreach organization Savage Sisters.

But as the drug supply changes, she said, it is vital for health officials to collect more data on other harms of drug use besides overdoses.

For example, medetomidine, another powerful animal tranquilizer not approved for human use, has supplanted xylazine in Philadelphia’s illicit opioid supply.

It causes intense withdrawal that has flooded emergency rooms with patients suffering from dangerous spikes in blood pressure and other heart complications. Some doctors have raised concerns that patients undergoing medetomidine withdrawal risk brain damage from high blood pressure.

Medetomidine was detected in about 15% of all fatal overdoses in Philadelphia between May 2024 and May 2025, according to preliminary city data obtained by The Inquirer this fall.

“It’s great they’re distributing naloxone at the rate they are. However, we have not really seen a ton of data on the complications that this polychemical substance wave is causing for people,” Laurel said.

“It’s a big area where we can look into the people we’re serving and the way their lives are being impacted by drugs.”

Teixeira da Silva said that city officials successfully pushed federal officials this fall to institute new medical billing codes for xylazine use and related amputations, a crucial step to allow hospitals to better track harms from the drug. They are hoping to do the same for medetomidine and its withdrawal symptoms.

“I definitely agree that we need a broader perspective in terms of the harms caused by drug use beyond death,” he said. “Of course, death is the worst harm. That has to be a metric that we continue to monitor and work toward zero.”