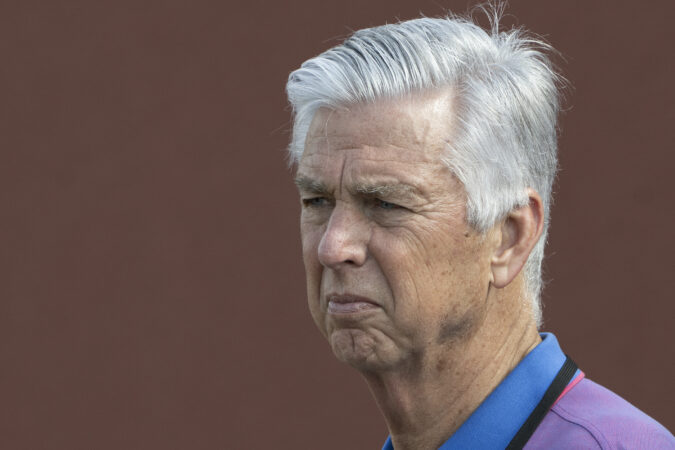

In October, in his season-ending news conference following a third consecutive playoff collapse, Phillies president Dave Dombrowski observed, correctly if not wisely, that Bryce Harper did not “have an elite season like he did in the past.”

Harper took offense. Phillies fans generally sided with Harper, who, on the day after Christmas, posted a video of himself on TikTok taking swings in a batting cage wearing a sweatshirt that said, “NOT ELITE.”

On Tuesday, in a hot-stove news conference after whiffing on top-level free agent Bo Bichette and instead re-signing J.T. Realmuto, Dombrowski observed, correctly if not wisely, “I think we’re content where we are at this point.”

This time, every Phillies fan took offense.

For days, the Phillies had the baseball world on their side. From Thursday at about 4 p.m. until midday Friday, they believed they’d come to a verbal agreement to land Bichette for seven years and $200 million. After Bichette backed out and signed with the New York Mets, the sports world sympathized with Dombrowski, who, in the middle of that same Zoom news conference Tuesday, said:

“It’s a gut punch. You feel it. You are very upset.” Another top Phillies official said he was “furious.” They were justified, and baseball commiserated.

But then, with free agents like Cody Bellinger and Framber Valdez still available, Dombrowski dropped “content” … and, well, Phillies nation, still stinging from playoff disasters, was not pleased.

With one simple sentence, Dombrowski and the Phillies went from being the victims of Bichette’s treachery to being the club that sat on its hands while its chief rivals, the Los Angeles Dodgers and Mets, spent ever more lavishly to pursue winning.

That’s mostly true. Still, context is important.

First, as it regards trade targets, Dombrowski can’t say he’s pursuing another team’s player. That’s tampering. Second, tipping his hand regarding any remaining free agents would be poor strategy. Third, he said, “I think.” The phone could ring at any time, be it a general manager proposing a trade or an agent proposing a deal.

Still, what Dombrowski said imparts a certain finality.

Or, if you’re a hopeful fan, a certain fatalism.

Which is fair.

Dombrowski noted that the Phillies spent money and made moves to remain competitive. Kyle Schwarber re-signed for five years and $150 million, Realmuto re-signed for three years and $45 million, and reliever Brad Keller (Brad Keller?) signed for two years and $22 million. They also traded reliever Matt Strahm for reliever Jonathan Bowlan (Jonathan Bowlan?).

But are they, as a whole, better?

No.

By no stretch of the imagination are they better than they were this time last year, when Zack Wheeler was healthy and Ranger Suárez was on the team.

And no, they’re not better than they were after they lost Game 4 of the NLDS, when they had Suárez and center fielder Harrison Bader.

They’re not better. They’re different, but not better.

They will gamble on outfielder Adolis García, whom they gave a one-year, $10 million deal in the hopes that, at 33, he will improve his .675 OPS and 44 home runs over the last two seasons. Those numbers are chillingly similar to those of the player he will replace, Nick Castellanos, who is one year older (he will be 34 in March), and managed an OPS of .719 and 40 homers in the same time span.

They will gamble that speedy rookie Justin Crawford can handle center field after acknowledging last year that Crawford might be better served playing in left. They will gamble that hard-throwing rookie Andrew Painter will relocate the command he lost in the minors in 2025 after elbow surgery in 2023 cost him two full seasons.

Prospects don’t necessarily make teams better; several studies reveal that more than half of the top 100 bust, and of the other half, only a handful make a significant impact. That’s fine. Unless you’re the Dodgers, with their unlimited budget, homegrown talent is the most efficient method to fill the roster.

The Phillies’ bullpen might be the one unit that is better than it was at the beginning and end of 2025. José Alvarado, who lost time to a PED suspension and an injury, will be back, paired with 100-mph closer Jhoan Duran, Dombrowski’s best deadline addition in years.

But the Phillies’ starters? Hardly.

Wheeler is the best Phillies pitcher since Steve Carlton. Since 2021, Suárez ranks seventh in Wins Above Replacement, at 17.7, ahead of Gerrit Cole and Valdez, but still almost 10 behind Wheeler, the leader. Wheeler and Suárez will be replaced by Painter and Taijuan Walker.

The lineup won’t be better, just older. The principals — Realmuto, Trea Turner, Schwarber, and Harper — will all be at least 33 by the end of the season. Thirtysomethings seldom improve with age. They just age.

Would Bichette have made the Phillies elite? No. Not elite like the Dodgers, who signed Kyle Tucker to a four-year, $240 million deal. That deal is what spurred Bichette to back out of his agreement with the Phillies, who, in turn, refused to even consider the opt-out years the Mets gave Bichette — a structure that puts all the risk on the team and none on the player. Dombrowski did the right thing, even if he said the wrong thing.

Bichette wouldn’t have made the Phillies elite. But he would have made the Phillies better, and he’d have made Dombrowski’s offseason “elite.”

Instead, Dombrowski is “content.”