Within the serpentine halls and stairways of Olivet Covenant Presbyterian Church, congregants have established several private, off-limits rooms ― each a potential last-stand space where members would try to shield immigrants from ICE, should agents breach the sanctuary.

Church leaders call them Fourth Amendment areas, named for the constitutional protection against unreasonable search and seizure. The plan would be to stop ICE officers at the thresholds and demand proof that they carry legal authority to make an arrest, such as a signed judicial warrant.

“It’s a protective space,” said the Rev. Peter Ahn, pastor of the Spring Garden church. “While you’re here, you’re safe, is what we want to assert.”

Could it come to that? A pastor confronting armed Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in the hallway of a church?

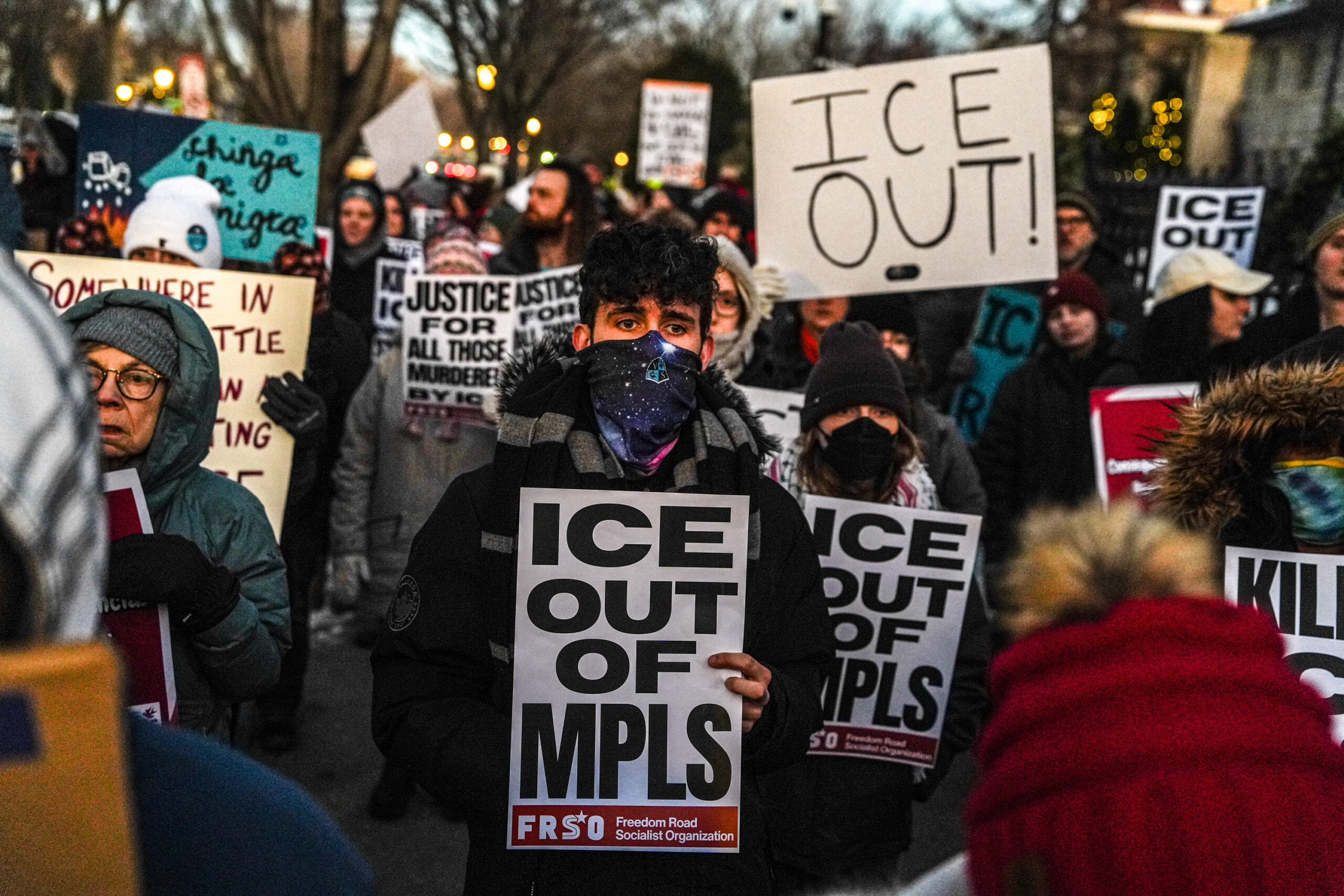

It’s impossible to know. But across Philadelphia, churches, community groups, immigration advocates, and block leaders are actively preparing for the time ― maybe soon, maybe later, maybe never ― that the Trump administration deploys thousands of federal agents. People say they must be ready if the president tries to turn Philadelphia into Minneapolis ― or Los Angeles, Chicago, or Washington, D.C.

Know-your-rights trainings are popping up everywhere, often to standing-room-only attendance, and ICE-watch groups are abuzz on social media.

The First United Methodist Church of Germantown held a seminar last week to learn about nonviolent resistance, “so that we will be ready for whatever comes,” said senior pastor Alisa Lasater Wailoo.

“That may mean putting our bodies in the path to protect other vulnerable bodies,” she said. “We’re seeing that in Minnesota.”

In Center City, Temple Beth Zion-Beth Israel has ordered 300 whistles ― portable and efficient tools to immediately alert neighbors to ICE presence and warn immigrants to seek safety.

“There was a sense of needing to support our neighbors if it comes down to it,” said Rabbi Abi Weber. “God forbid, should there start to be ICE raids in our neighborhood, people will be prepared.”

In other places around the country, immigrant allies have similarly readied themselves for ICE’s arrival, and organized to react in concert when agents show up.

In Washington state, the group WA Whistles has distributed more than 100,000 free whistles to create what it calls “an immediate first line of community defense.” Chicago residents set up volunteer street patrols to warn immigrants of ICE and to contact family members of those detained. In Los Angeles, people raised money to support food-cart vendors, and organized an “adopt a corner” program to protect day laborers who seek work outside Home Depot stores.

Ask Philadelphia groups that advocate for immigrants — 15% of the population, including about 76,000 who are undocumented — and they say ICE isn’t about to land in the city. It’s been here.

The agency’s Philadelphia office serves as headquarters not just for the city but for all of Pennsylvania and for Delaware and West Virginia as well. Arrests take place every day in the Philadelphia region.

“You all seem to be ‘preparing’ for something that’s already happened,” veteran activist Miguel Andrade wrote on Facebook.

What has changed, however, is the dramatic escalation in ICE enforcement, particularly visible in Democratic-run cities like Minneapolis, where agents fatally shot two U.S. citizens in January.

ICE detained 307,713 people across the country in 2025, a 230% increase over the 93,342 in 2024. What federal immigration agencies record as detentions closely mirror arrests.

Today residents in communities like Norristown and Upper Darby see ICE agents on the streets all the time. Cell phone videos have captured violent footage, including the smashed front door of a Lower Providence home after agents made an arrest on Feb. 9, and two people roughly pulled from a car in Phoenixville earlier this month.

For immigrants who have no legal permission to be in the U.S. ― an estimated 14 million people ― the rising ICE presence steals sleep and peace of mind. They know not just that they could be arrested and deported at any moment, which has always been true, but also that the U.S. government is expending vast resources to try to make that happen.

A woman who came to Philadelphia from Jamaica last year, and who asked not to be identified because she is undocumented, said she rarely leaves her home. She said she steps outside only to go to the grocery store, a doctor, or an attorney.

She recently asked her daughter to check something on the computer, and the girl balked ― afraid to even touch the machine, worried that ICE could track her keystrokes and identify their location, the woman said.

“How can I tell her it’s going to be OK when I don’t know it’s going to be OK?” asked the woman, who came to the U.S. to escape potential violence in Jamaica. “You come here expecting freedom, but here it’s like you’re in jail except for the [physical] barriers of the four walls.”

Even as arrests have soared, Philadelphia has been spared the federal intrusions visited on other American cities.

Why?

Some say President Donald Trump doesn’t want to ruin the summer celebration of the nation’s 250th birthday, or spoil the grandeur of the World Cup or Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game. Others suggest that he might be timing an ICE deployment to do exactly that.

That as Philadelphia City Council prepares to consider “ICE Out” legislation that would make it more difficult and complicated for the agency to operate in the city.

Trump told NBC News this month that he is “very strongly” looking at five new cities.

Some people are not waiting to see if Philadelphia is on the list.

The monthly Zoom meeting of the Cresheim Village Neighbors usually draws about 20 people. But a hundred logged on in January to hear a presentation: What to do if/when ICE comes to our neighborhood.

The short advice: If it happens, get out your phone and hit “record.”

“If I see ICE agents, I will film,” said neighbors group coordinator Steve Stroiman, a retired teacher and rabbi. “I have a constitutional right to do that.”

In a sliver of University City, Miriam Oppenheimer has helped lead three block meetings where neighbors gathered to discuss how they would respond.

They set up a Signal channel so people can communicate. And they formulated a loose plan of action: People will come outside their homes and take video recordings ― and try to get the names and birth dates of anyone taken into custody, so they can be located later.

“Courage is contagious,” Oppenheimer said. “Everybody is waiting for somebody else to do something, but we have to be the ones.”

Inside Olivet Covenant Presbyterian Church, doorways to some rooms now bear black-and-white signs that say, “Staff and authorized personnel only.”

Issues around ICE access to churches have become more urgent since Trump rescinded the agency policy on “sensitive locations,” which had generally barred enforcement at schools, hospitals, and houses of worship.

Legal advocates such as the ACLU say ICE agents can lawfully enter the public areas of churches, including the sanctuaries where people gather to worship. But to go into private spaces they must present a warrant signed by a judge.

“There are many front lines right now,” said Ahn, the Olivet pastor. “We’re not trying to be simply anti-ICE, or anti-anybody. We’re just trying to be for the rights of the Fourth Amendment.”

Staff writer Joe Yerardi contributed to this article.