Two top trans-Atlantic shippers are moving their cargoes to Philadelphia-area terminals, boosting longshore and trucking jobs, and ending Baltimore port calls as work drags on replacing the Key Bridge, whose collapse 21 months ago crippled ship traffic to that city’s harbor.

A.P. Moller-Maersk, based in Denmark, and German-based Hapag-Lloyd AG, which each rank among the top five global container companies and operate hundreds of ships carrying millions of trailers, have switched a major route for their Gemini joint venture to the PhilaPort’s Packer Avenue Marine Terminal, effective Jan. 4, Philadelphia-based Holt Logistics told customers in a note Wednesday.

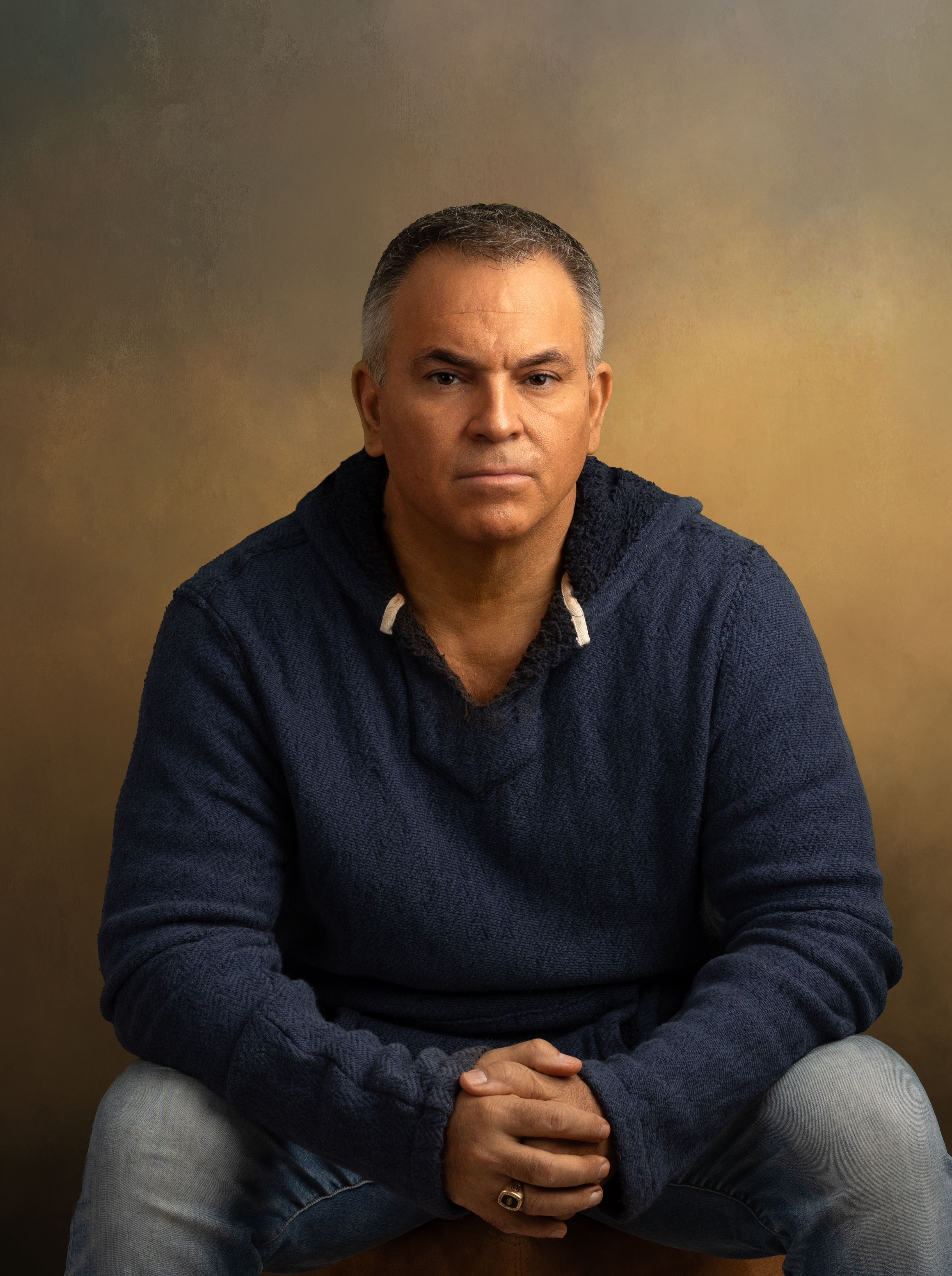

“Rising tide lifts all boats, and that includes the waterfront labor, plus all the other ancillary support folks that run freight, handle it, and store it,” said Leo Holt, whose family operates Holt Logistics. “It’s a big win for Philadelphia, and a harbinger of good things to come.”

Holt, based in Gloucester City, is expanding its container operations in the Port of Philadelphia on land acquired by state port agency PhilaPort in South Philly. That includes a new cold-storage warehouse. Plans are still in the works for 152 acres bought with state funds for more container and automotive storage.

Philadelphia’s port handles wine, meat, furniture, car parts, drugs, and many other container goods. The region also exports drugs, steel, and machine and vehicle parts. Singaporean-owned Penn Terminals in Delaware County and the Port of Wilmington, Del., also handle containers.

Philadelphia recorded the equivalent of 841,000 20-foot trailer equivalents (TEUs) through area ports last year and expects to report more for 2025, even before the new service and additional lines to Australia and New Zealand start next year. The agency’s goal is to boost that to more than 2 million a year with the planned expansion, said spokesperson Sean Mahoney.

Philadelphia-area container shipping has nearly doubled since Jeff Theobold took over as PhilaPort executive director in 2016, while overall U.S. container volume has risen about 30%. Theobold plans to retire in June, two months after PhilaPort’s new cruise ship terminal is scheduled to open in Delaware County near Philadelphia International Airport. The agency is searching for a successor.

Philadelphia “will replace Baltimore” on a major trans-Atlantic route used by Hapag-Lloyd and Maersk, according to a report in Freightwaves, which noted Baltimore container traffic fell from 1.3 million 20-foot-trailer equivalents in 2023 to around 700,000 last year, even before the switch. Each ship on the route carries 5,000 to 6,500 TEUs.

The new route also moves container ships between Newark, N.J., terminals that handle New York cargoes; Norfolk, Va.; St. John in Canada; the British port of Southampton; the Netherlands’ giant Rotterdam port at the mouth of the Rhine; and the German ports of Wilhelmshaven and Hamburg.

That adds Germany to the list of countries with direct service to Philadelphia, Mahoney said. There’s no guarantee that all the Baltimore cargoes will shift to Philadelphia.

Philadelphia also expects more ships from Australia and New Zealand ports as two lines that service those countries via the Panama Canal have recently added Philadelphia as their Northern U.S. port, Mahoney said. Already those countries and other South Pacific ports make up close to one-quarter of the Philadelphia area’s container cargoes, making it the leading East Coast port for shipments from that region. PhilaPort expects the lines will attract cargoes now shipped to Baltimore, New York, or Norfolk.

Newark is the largest port complex in the Northeast. Philadelphia competes with Baltimore and southern ports for container and automotive cargoes.

Philadelphia has the fastest arrival-to-departure time of any North American port, reducing shipping costs, according to a recent report by a World Bank subsidiary. Holt attributes that to cooperation between unions including International Longshoreman’s Association, and Teamsters locals, port agencies, and owners such as PhilaPort, and his own organization.

Next year Holt plans to add two more tall cranes to the small forest of ship unloading equipment it maintains in South Philly and Gloucester City.