It’s been 10 years since OpenAI was set up as a nonprofit by Sam Altman, Elon Musk, and other software developers and investors, friends, and rivals who didn’t quite trust each other to run a traditional for-profit business with explosive potential.

Chartered in business-friendly Delaware like most big corporations, OpenAI laid out its public purpose in a mission statement: “to ensure that artificial general intelligence — AI systems that are generally smarter than humans — benefit all of humanity.”

A decade later, its best-known product, ChatGPT, claims more than 700 million weekly users.

Delaware officials who monitor the state’s nonprofits took a particular interest as OpenAI became so valuable, and so contentious, that the San Francisco-based startup ballooned into an enterprise requiring multibillion-dollar investments and sought to restructure as a for-profit company.

“We realized building [artificial general intelligence] will require far more resources than we’d initially imagined,” the company wrote in an open letter last year, explaining its plans. In fact, OpenAI had set up for-profit affiliates at least as far back as 2019.

But the company said it needed more corporate flexibility if it was to bring in the billions needed to fund high-speed data centers full of Nvidia chips and other systems that could withstand intense AI searches and commands.

Recent investments have boosted OpenAI’s value to around $500 billion. That’s more than Musk’s SpaceX or Jeff Yass-backed ByteDance (which owns TikTok) or any other private firm — underscoring the bonanza potential and the returns investors hope to realize.

So it wasn’t surprising last year when OpenAI, which Altman runs, announced plans to raise billions of new dollars by ending its previous limits on investor profits — or that Musk, now owner of a competitor, X.AI, and others, promptly sued, challenging terms of their plan.

That’s when Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings, and California Attorney General Rob Bonta, stepped up.

Jennings and Bonta filed court papers challenging the proposed business structure — not to stop it, as Musk wanted, but to ensure that the public interest was somehow protected, so OpenAI wouldn’t stray from what the company has called its “save the world” mission.

Critics, including some in Congress, have worried that ChatGPT is prone to surveillance abuse, crime and encouraging self-harm.

The final plan, as OpenAI posted it last month, preserves the original company as the nonprofit OpenAI Foundation but moves its businesses to a new, largely investor-owned Delaware “public-benefit corporation.”

A public-benefit corporation is a for-profit company but does not have the usual legal obligations to enrich investors before anything else, freeing directors to act in favor of public goals even if it hurts sales or profits.

A public-benefit corporation provides “a clear and durable vehicle” for companies whose goals go beyond shareholder gains, says Lawrence Cunningham, who runs the Weinberg Corporate Governance Center at the University of Delaware. “I like seeing it used in that way here.”

State intervention at the corporate-charter level “does not happen often” and usually involves questions about nonprofit hospitals’ business activities, said Mat Marshall, spokesperson for Delaware AG Jennings.

Jennings hired lawyers from Manhattan-based Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman and financial analysts from Moelis & Co. to buttress the state’s fraud and consumer protection director, Owen Lefkon, in talks with OpenAI.

What changes for OpenAI

At first, OpenAI planned to pay off its nonprofit obligations by leaving those to a large charitable foundation and then move forward as a typical for-profit company, still professing public goals but responsible to private investors.

Lawyers for the two states argued that the company’s public mission had to survive the restructuring.

OpenAI “is the world leader in the artificial intelligence industry,” but it needs guidelines as it funnels massive information about science, medicine, and communities to private, commercial, and government users, and power to “hold OpenAI accountable” for the safety of those whose information is raw material for AI, Jennings said in a statement.

The foundation also needed some way to keep control over the company, alongside its powerful new for-profit investors. The nonprofit has kept the power to name and remove board members for the business.

OpenAI’s Safety and Security Committee will remain in place, with “authority to oversee and review the safety and security processes and practices of OpenAI” and the companies it controls, even halting new AI systems if it finds them dangerous, or taking time to resolve ambiguities.

Zico Kolter, professor of machine learning at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, will continue to head the safety committee, attend the corporation’s board meetings, and receive “all director information regarding safety and security.”

And the states will be given “advance notice of significant changes” in governance.

In a statement praising the new structure, OpenAI chair Bret Taylor, creator of Google Maps and a former Facebook and Twitter officer, acknowledged changing the plan in discussion with Delaware and California.

He said the parent, now called the OpenAI Foundation, will own around one-quarter of the business group. Outside investors include Microsoft, Japanese investor Softbank, company employees, and other investors, with room for more.

Besides keeping the business subordinate to the foundation’s mission, Taylor wrote that the foundation will set aside $25 billion: for “open-sourced and responsibly-built” health data sets to speed up diagnostics, treatments and cures; and to fund AI security to protect power grids, banks, governments, companies and individuals” from AI abuse.

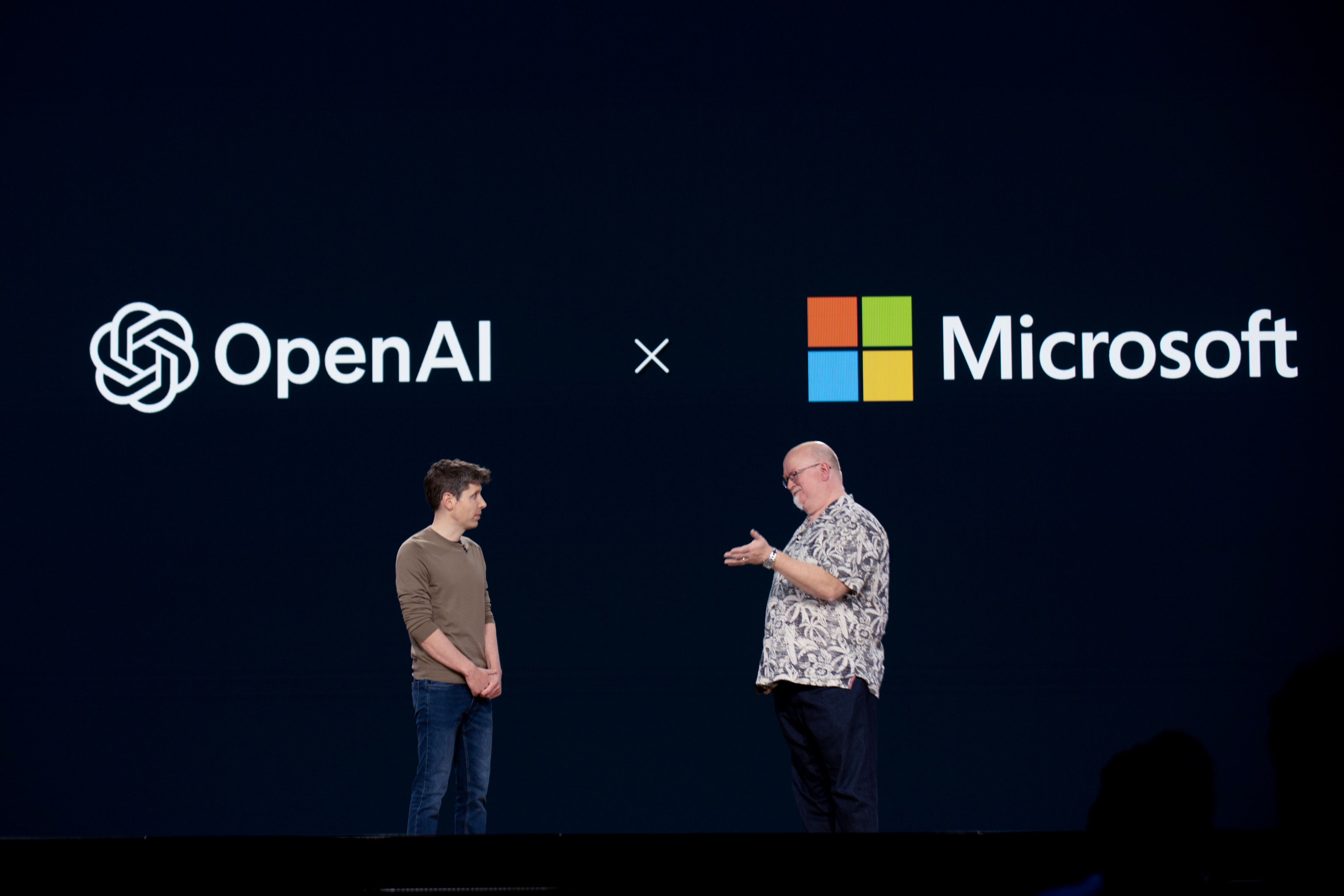

Microsoft shows its power

Since the restructuring, Microsoft has revealed new details of its already-lucrative agreement with OpenAI, the noted Philadelphia-based accounting professor and researcher Francine McKenna and her investigative partner Olga Usvyatsky wrote last week in McKenna’s newsletter, The Dig.

Microsoft has invested $11.6 billion in OpenAI over several years (and promised at least $1.4 billion more).

Thanks to exploding OpenAI sales and additional private investments, Microsoft says its investment is now worth $135 billion. That’s more than 10 times what the company paid. Microsoft is the largest OpenAI shareholder, with around 27%. .

Under a recent agreement following the restructuring, Microsoft said, OpenAI promises to buy another $250 billion in Microsoft Azure cloud networking and other services but also gains the right to form more partnerships with other companies.

The companies also enjoy a revenue-sharing agreement — the first time that’s been disclosed, according to McKenna and Usvyatsky — though details will have to wait for future disclosure.