The school closures and consolidations proposal for Philadelphia schools that was announced in January was not surprising. The district, like many districts across the country, has signaled that it is grappling with declining enrollment, underutilized buildings, and tight budgets. The issue is so pervasive that the consulting firm Bellwether published a full report about it last fall called “Systems Under Strain: Warning Signs Pointing Toward a Rise in School Closures,” warning that many districts would soon face similar decisions.

The process isn’t surprising, either. Seattle similarly wrestled with a school closures plan before it got so complicated that the city simply dropped the issue after intense community backlash, concerns over student well-being, and the realization that there wasn’t a clear plan for how much the closures would chip away at the roughly $100 million budget deficit.

The situation in both Philadelphia and Seattle has many similarities to Chicago’s school closures in 2013. Chicago Public Schools closed 47 elementary schools — the largest national mass closures up to that point.

My colleagues and I at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research studied that process, releasing reports on families’ priorities and choices in finding new schools, and on staff and students’ experiences, including academic outcomes. The findings from our research offer important lessons and considerations for district leaders and community members in Philadelphia today.

First, school is a very personal space and choice for students and families. Families assess the quality of a school in many different ways, from class size to specific course offerings to the availability of specific extracurriculars.

A school’s reputation, sometimes going back multiple generations, is often a factor. And both safety and accessibility — proximity and available transportation — are always paramount. Closing a school isn’t just an administrative change; it is a profound disruption of community and family life.

Second, logistics matter enormously and proved more difficult than expected in Chicago. The management of closing some schools and merging into others was a massive pain point in Chicago’s school closures.

Some teachers could not find their personally purchased furniture, technology, and classroom supplies. Critical details were overlooked, which caused significant challenges for staff and students. Closures require thorough and transparent operational planning.

But last and most importantly, it is critical to consider the effect of school closures on the people who experience them. In our interviews with both students and staff, we repeatedly heard that they wished their grief and loss had been acknowledged, validated, and addressed.

When we looked at the data, we found that test scores dropped for students whose schools closed — and the drops started the year potential closures were announced, reflecting the effects of uncertainty and upheaval. Test scores also dropped for students whose schools were “receiving schools,” enrolling many of the affected students.

Our University of Chicago colleague, professor Eve L. Ewing, wrote in her commentary in our report that “we must ask how and why we continue to close schools in a manner that causes ‘large disruptions without clear benefits for students.’”

The way this plays out in Philadelphia matters, as young people, families, and educators are already emphasizing. In Chicago, school staff wished for more communication, more transparency, more training on merging school communities, longer-term transitional funding, and more emotional support for adults, whose feelings were still raw three years later when we interviewed them.

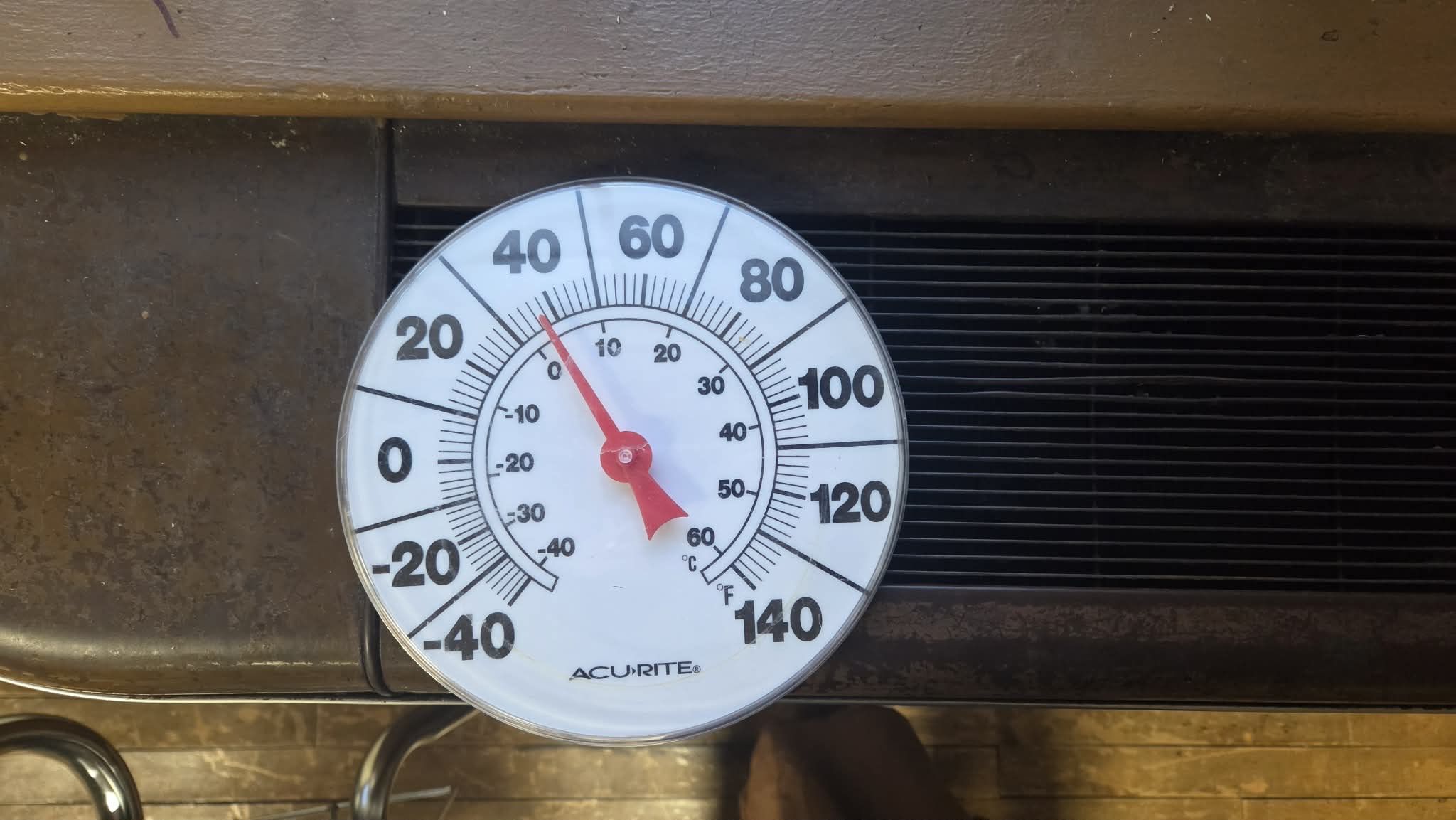

Students wished school actions provided better facilities, from building and green space to sufficient toilet paper and warm water. And they wished they had more counselors and social workers, and general emotional support from all school staff, who were, themselves, grieving. Simple yet powerful reminders of what makes schools feel like places of care, connection, and community.

In 2023, our fantastic Chicago education reporters covered the 10-year anniversary of Chicago’s massive school closures in Chalkbeat Chicago and in a WBEZ/Chicago Sun-Times collaboration. The students, families, neighbors, and staff shared similar messages in those stories as they had in our research: being told one thing and experiencing another; seeing the process as “hurtful” and without any benefit to young people or the community; wishing they could see the district and the city investing in schools, housing, and community resources where they live.

Regardless of what final decisions are made, a difficult path lies ahead for school communities across Philadelphia. Chicago’s experience tells us that any district considering school closures needs to plan meticulously, communicate frequently and transparently, and keep the experiences of students, families, and school staff at the center of the process.

Marisa de la Torre is managing director and senior research associate at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research, part of the Kersten Institute for Urban Education within the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice.