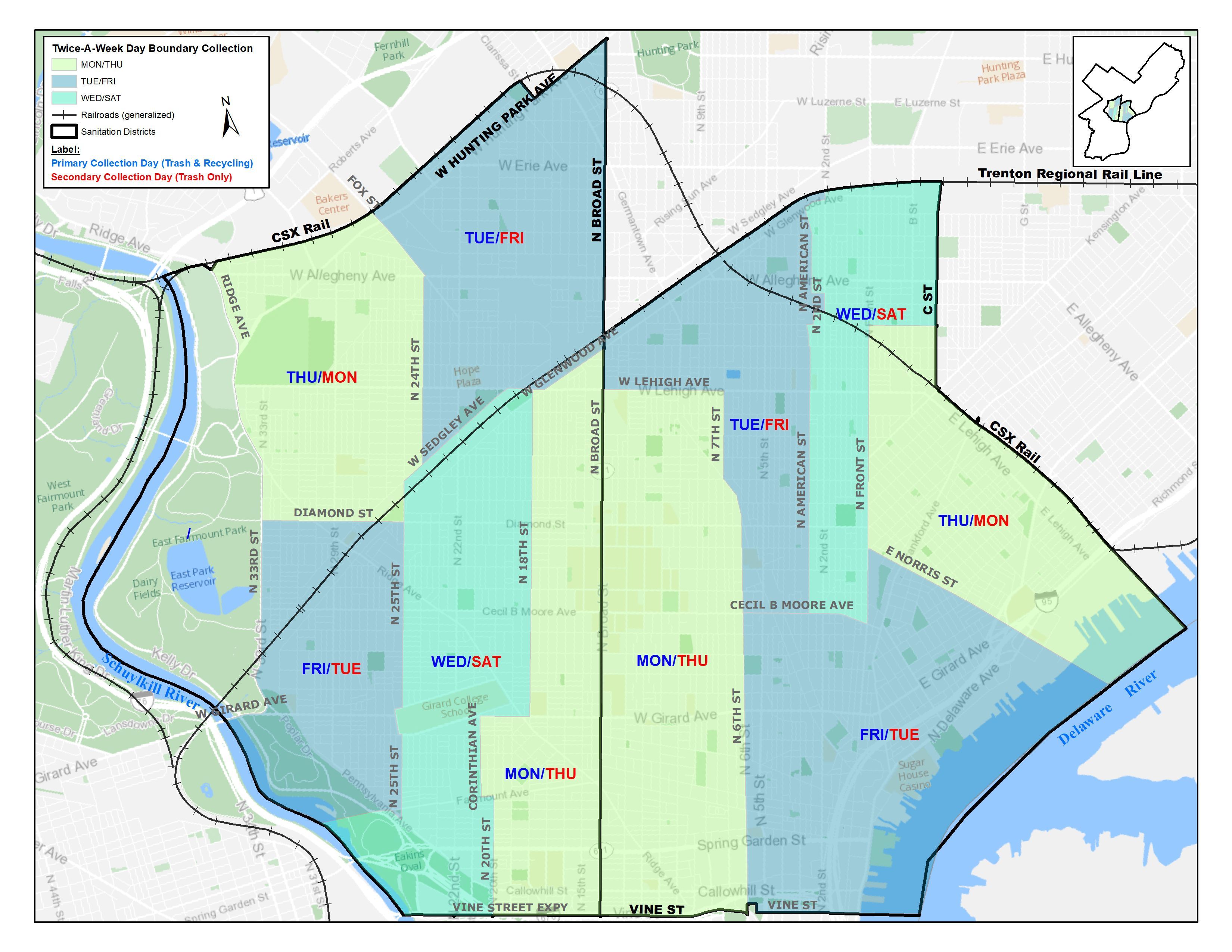

Lil’ Filmmakers, a Roxborough-based nonprofit, was supposed to have $170,000 in the bank.

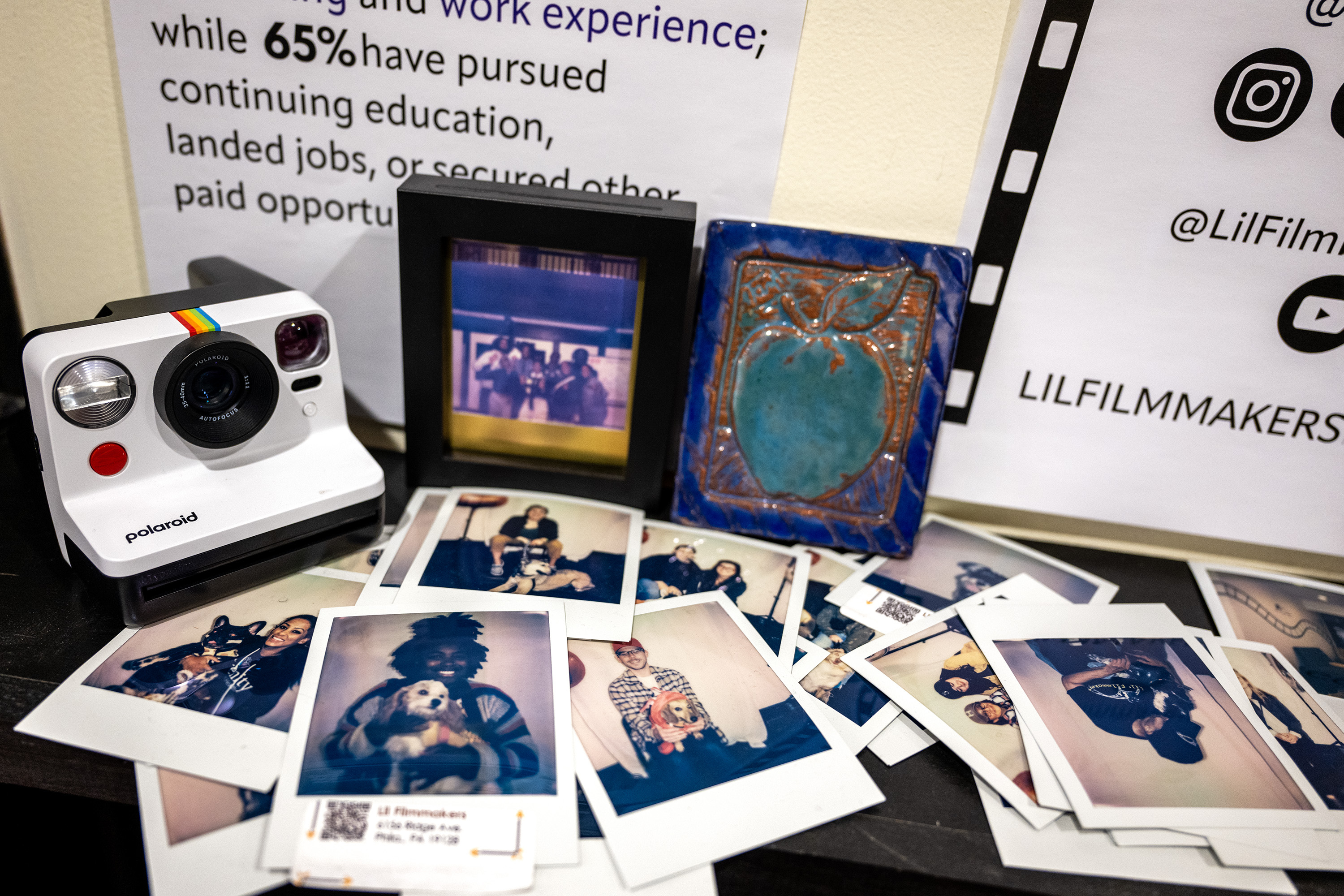

The mission of helping young people become storytellers through film and media had caught the attention of major donors in 2025. The city awarded it a $28,000 anti-violence grant, and one of Michael Jordan’s charitable organizations issued a separate $35,000 grant. Funding should not have been a problem, according to CEO Janine Spruill, who started the program in 1999.

But on Aug. 27, neither she nor her four staffers, nor her summer program participants, had gotten paid by the Federation of Neighborhood Centers, the Philadelphia nonprofit that managed their money.

She remembers FNC staff telling her they had decided not to process payroll because they were trying to “figure some things out.” Without specifics, Spruill walked away suspecting the worst.

“I went into a bit of a panic mode,” Spruill said, upset that she hadn’t even been given a heads-up. “I ended up crying my eyes out because I said, ‘Oh, my God, I raised all this money, and they’re telling me they don’t have it.’”

Other organizations that had contracts with FNC soon realized that they, too, were having issues accessing their funds. They reported overdue invoices, payroll issues, and spotty communication with FNC.

As the weeks turned into months, Spruill said, FNC would not let her access the money she had raised. She had to launch emergency fundraisers.

The announcement many of the groups dreaded arrived in November. FNC’s grant management services — known as a fiscal sponsorship program in the nonprofit world — would shut down Dec. 31.

“This choice does not come lightly,” said FNC’s announcement on its website. “It comes after years of carrying work that we believed in wholeheartedly — often beyond our capacity — because we care deeply about every project, every leader, and every community member who trusted us with their mission.”

FNC’s collapse, by its own admission, is a story of an organization that grew too quickly and let basic accounting principles go by the wayside. Demir Moore, the nonprofit’s new CEO as of Aug. 26 and a former Lil’ Filmmakers intern, insisted FNC’s collapse was due to a “lapse of management” and “absolutely not attributable to malfeasance or embezzlement.”

FNC spent itself into a deficit over the course of years, continuously using money belonging to one group to pay for another, according to Thaddeus Squire of Social Impact Commons, an organization aiding FNC as it winds down.

“That deficit started to become unrecoverable,” he said. “Money that was borrowed was not put back.”

Moore declined to say how much money FNC has or how many groups are affected by the end of the fiscal sponsorship program. FNC has about 50 groups on its rolls, he said, but some have not been active or have no funds with the nonprofit.

Still, it is unclear how the nonprofit was able to operate the way it did for years. Sorting out just how FNC’s fiscal sponsorship program unraveled is going to take time, Moore said, declining to comment on leadership turnover in the last year.

Attempts to reach past FNC leadership for insight on what transpired were unsuccessful.

And while Moore described a round-the-clock effort to sort out how much every group should have in its account, he would not say for certain whether groups would get all their funds back by the time FNC shuts down.

When the ‘safe approach’ loses control

When run right, a fiscal sponsor can be a boon to newer community groups that do not have a tax-exempt status. By contracting with fiscal sponsors, which are registered as 501c3s, these smaller groups can apply for grants.

Donors are left assured that a more established nonprofit is guiding the smaller or newer group, said Brian Mittendorf, the H.P. Wolfe Chair in Accounting at Ohio State University, who specializes in nonprofit accounting.

“Financial difficulties at fiscal sponsors are much less frequent just because their position … is typically an indicator that they have strong financial controls and other infrastructure in place,” he said, adding that signing with a fiscal sponsor is “often viewed as the safe approach.”

Fiscal sponsors can also be of much help to registered nonprofits that would rather focus on providing services than on managing administrative tasks.

In exchange for a fee, the sponsor signs on to manage and distribute grants, offer reports, and take on a range of tasks, such as payroll or legal questions, giving community groups peace of mind.

For Lil’ Filmmakers, the promise of back-office support led it to contract with FNC nearly a decade ago. Spruill said the monthly accounting report FNC sent her would sometimes require adjustments, but she cited no major issues until this year.

The first red flag came in March. Spruill said FNC did not pay the rent for Lil’ Filmmakers’ studio in Roxborough. FNC ultimately took care of the late fees and cut the rent check, so Spruill said she chalked it up as a one-time occurrence.

What Spruill and other community group leaders could not see was an organization Moore said could not keep up with its own expansion. The nonprofit recorded a revenue of $774,000 in 2019 tax filings, which peaked at $4.76 million in 2023.

A years-old message from then-CEO Jerry Tapley remained on the FNC website until this summer, touting more than 50 projects ranging from urban farming and the arts to animal rescue work. The organization’s work affected 250,000 people annually in “Philadelphia and beyond,” he wrote.

Moore said that as the nonprofit grew, FNC was not always collecting key documentation, such as receipts. Community groups were allowed to draw checks for funds they did not have, and balance statements given to groups were out of date or inaccurate.

When Moore stepped down as FNC board president and took over as CEO, the first thing he did, in an attempt to take stock of finances and accounts, was freeze outgoing payments.

While Moore described the move as a necessary first step, community groups struggled to pay for basic overhead, and some sought outside help. Soon, Philanthropy Network Greater Philadelphia and Social Impact Commons, an organization that supports fiscal sponsors, were working with FNC — but it was too late.

There did not appear to be any nefarious intent behind the mismanagement, Social Impact Commons’ Squire said, but FNC’s system allowed some projects to spend into the negative and for debt to snowball.

Social Impact Commons recommended FNC shut down its fiscal sponsorship program and “stop trying to catch up,” according to Squire.

Clarity may not come for at least several more weeks

Sharon Wilson, Lil’ Filmmakers’ attorney, said one of her biggest frustrations is what she finds to be a general lack of transparency as FNC winds down operations, despite her repeated requests for updates in writing.

“All of the information that was learned about FNC’s internal problems, and the fact they were failing other nonprofits other than Lil’ Filmmakers, was all gleaned outside of them,” she said.

The way Moore explains it, the reason FNC has not outright said all community groups would be made whole is that figuring out who is owed what will take at least several more weeks. He said FNC does have funds available, but until the reconciliation process is complete, “no final conclusions can be made about individual project balances or what each project’s final financial position will be.”

For now, multiple third parties, including the city, are working to move the process along.

The Philadelphia Office of Public Safety, for example, said Lil’ Filmmakers and three other anti-violence grant recipients with awards managed by FNC are in different parts of the process. Together, the groups had roughly $380,000 in city-issued funds awarded, which the city said are largely accounted for.

Though the final spending report for Lil’ Filmmakers remains in dispute, it might be resolved by the end of the month, according to the city.

In the meantime, a public safety office spokesperson said staffers were working with organizations to help close their accounts with FNC and offering technical assistance to its grant recipients, including bookkeeping and fiscal sponsor matchmaking.

Still, the office said, there is not much it can do for other grants awarded by other donors.

Complicating money matters further, some organizations used a California-based fundraising platform called Flipcause to collect donations. Last month, California’s attorney general sent a cease-and-desist order to the company, ordering it to halt operations after more than a dozen nonprofits in the state accused Flipcause of withholding funds. The platform also faces a class-action lawsuit in federal court.

In all, Moore said, FNC organizations have about $100,000 being withheld by Flipcause; Lil’ Filmmakers is not one of them.

Moore did not rule out that some groups might have less in their accounts than they were initially told in their FNC financial statements because of accounting discrepancies.

Squire went a step further, adding that philanthropic fundraising would be necessary.

“We’re cautiously optimistic that despite a lot of genuine harm that’s been done, that we can at least get people sorted out and back on their feet in the next few months,” Squire said.

The goal, he said, is that each of the groups needing to be placed with a new fiscal sponsor to access their money will have a new one by the end of the first quarter of 2026.

The results of the internal audits will likely determine any legal recourse or investigations. For example, the Pennsylvania Bureau of Corporations and Charitable Organizations, part of the Department of State, can impose fines against charities and revoke their registrations if they are found to be violating the state laws that govern them.

But Spruill, her staff, and her teaching artists cannot afford to keep waiting.

Lil’ Filmmakers has launched another fundraising campaign, this time for $50,000, so programming can continue uninterrupted.

When speaking about the financial setback, Spruill remains defiant.

“We refuse to let this stop the stories that need to be told,” reads her plea to donors.