DALTON, Ga. — Bob Shaw glared at the executives from the chemical giant 3M across the table from him. He held up a carpet sample and pointed at the logo for Scotchgard on the back.

“That’s not a logo,” fumed Shaw, CEO of the world’s largest carpet company, one attendee later recalled. “That’s a target.”

Weeks earlier, 3M Company announced it would reformulate its signature stain-resistance brand under pressure from the Environmental Protection Agency because of human health and environmental concerns.

Mills like Shaw’s had been using Scotchgard in carpet production, releasing its chemical ingredients into the environment for decades. And on a massive scale: The shrewd CEO built Shaw Industries from a family firm in Dalton, Georgia, into a globally dominant carpet maker worth billions.

“I got 15 million of these out in the marketplace,” Shaw told his 3M visitors. “What am I supposed to do about that?”

A 3M executive replied that he didn’t know. Shaw threw the sample at him and left the room.

The answer to Shaw’s Scotchgard question from that moment in 2000 would be the same as that of the broader industry. Carpet makers kept using closely related chemical alternatives for years, even after scientific studies and regulators warned of their accumulation in human blood and possible health effects. Customers expected stain resistance; nothing worked better than the family of chemicals known as PFAS.

A lack of state and federal regulations allowed carpet companies and their suppliers to legally switch among different versions of these stain-and-soil resistant products. Meanwhile, the local public utility in Dalton responsible for ensuring safe drinking water coordinated with carpet executives in private meetings that would effectively shield their companies from oversight.

Year after year, the chemicals traveled in water discarded during manufacturing from mills across northwest Georgia, eventually reaching a river system that provides drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people in Georgia and eastern Alabama.

The pollution is so bad some researchers have identified the region as one of the nation’s PFAS hot spots. Today, the consequences can be found everywhere. PFAS, often called forever chemicals because they can take decades or more to break down, are in the water and the soil.

They’re in the dust on floors where children crawl, the local fish and wildlife, and as ongoing research has shown, the people.

Doctors have few answers for those like Dolly Baker who live downriver from Dalton’s carpet plants. She recently learned her blood has extraordinarily high PFAS levels.

“I feel like, I don’t know, almost like there’s a blanket over me, smothering me that I can’t get out from under,” she said. “It’s just, you’re trapped.”

An investigation by newsrooms including The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Associated Press and FRONTLINE (PBS) has revealed how the economic engine that sustained northwest Georgia contaminated the area and neighboring states, too. Downriver from Dalton, AL.com found cities in Alabama are struggling to remove PFAS from drinking water. And in South Carolina, The Post and Courier traced a local watchdog’s discovery of forever chemicals to a river by a Shaw factory.

The full story of Georgia’s power structures prioritizing a prized industry over public health is only now emerging through dozens of interviews and thousands of pages of court records from lawsuits against the industry and its chemical suppliers. Those records, including testimony from key executives, emails and other internal documents, detail how carpet companies benefited from chemistry and regulatory inaction to keep using forever chemicals.

All the while, the mills still hummed.

Pointing fingers in a company town

A sign welcomes Dalton’s visitors to the “Carpet Capital of the World.”

Fleets of semitrucks stamped with company logos rumble out of behemoth warehouses. Textiles have employed generations here, propelling the city from 19th-century cotton mills into a manufacturing hub — and the region into a supplier of carpet to the globe.

The durability that makes PFAS so good at protecting carpets from spilled tomato sauce and muddy boots lets them survive in the environment. It also makes them dangerous for humans. Because they bind to a protein in human blood and absorb into some organs, PFAS linger.

The blood of nearly all Americans has some amount of the chemicals, which have been used in a variety of consumer products: nonstick cookware, waterproof sunscreen, dental floss, microwave popcorn bags.

Few industries used them as much as carpet did in northwest Georgia. While huge amounts were needed for stain resistance on an industrial scale, minuscule amounts — the equivalent of less than a drop in an Olympic-sized swimming pool — can make drinking water a health risk. For certain PFAS, U.S. regulators now say no level is safe to drink.

More than a year before the Scotchgard announcement in 2000, 3M informed Shaw Industries and its biggest competitor, Mohawk Industries Inc., that it was finding Scotchgard’s chemical in human blood and that it stayed in the environment, 3M records show.

Carpet executives have long insisted they are not to blame. They point out that 3M and fellow chemical manufacturer DuPont assured them their products were safe, for decades hiding internal studies that were finding harm to the environment, animals and people.

Shaw and Mohawk both said they relied on and complied with regulators and stopped using PFAS in U.S. carpet production in 2019.

In an interview, a Shaw executive said the company acted in good faith as it worked hard to exit PFAS as quickly as suitable substitutes could be found.

“Hindsight is 20/20,” said Kellie Ballew, Shaw’s vice president of environmental affairs. “I don’t think that we can call into question our intentions. I think Shaw had every good intention along the way.”

Shaw in a follow-up statement said it complied with its wastewater permits and took guidance from chemical companies, some of which “instructed Shaw to put spills of product into the public sewer system.”

Mohawk declined an interview request, instead referring to a 2024 filing in its lawsuit against chemical companies: “For decades, DuPont and 3M sold their carpet treatment products to Mohawk without disclosing the actual or potential presence of PFAS in their products.”

Later, in response to detailed questions, Mohawk attorney Jason Rottner wrote that, “Any PFAS contamination issues in northwest Georgia are a problem of the chemical manufacturers’ making.”

Now, uncertainty and feelings of betrayal are boiling across the region. Communities fear their drinking water is unsafe and local governments say the problem is too vast for them to fix alone.

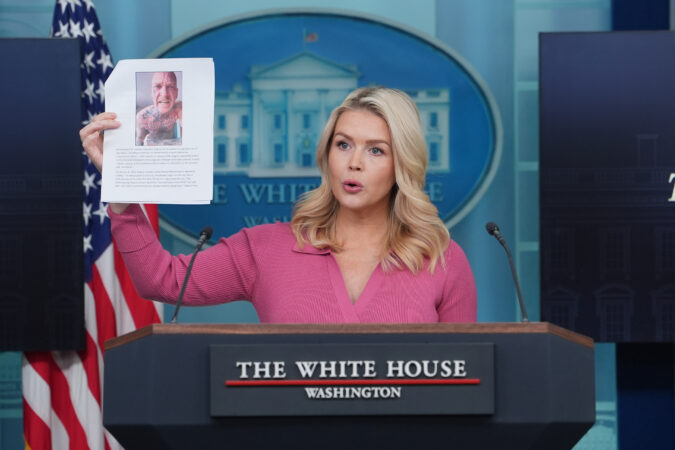

In Washington, Republicans and Democrats alike have been slow to act. Under President Joe Biden, the Environmental Protection Agency in 2024 established the first PFAS drinking water protections. The Trump administration has announced plans to roll back some and delay enforcement of others.

The agency declined interview requests but in a statement said it is committed to combating PFAS contamination to protect human health and the environment, without causing undue burden to industry.

Georgia’s regulatory system has done little to scrutinize PFAS and depends mostly on industry to self-report chemical spills, imposing modest penalties when companies do. The Georgia Environmental Protection Division, which declined an interview request, said it “relies on the expertise of” the EPA.

Meanwhile, carpet makers still can’t seem to shake PFAS. Just last year, EPA concluded “PFAS have been and continue to be used” by the industry, based on wastewater testing. The agency did not name companies and said it’s unclear whether the chemicals were from current or prior use.

The mess in northwest Georgia has led to a series of lawsuits over the past decade with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake.

Buried in this avalanche of litigation, finger-pointing and politics are the people who live here. They have been forced to navigate a public health and economic crisis of a magnitude still not fully understood.

“They ought to have to clean this land up,” Faye Jackson said, referring to carpet companies. A former industry worker, she raised her family in a house next to a polluted river and has elevated PFAS levels in her blood. “They ought to have to pay for it.”

The creek ran blood red

Lisa Martin watched the creek beside the Mohawk Industries mill run red with carpet dye.

It was one of her first days as a planning manager at Mohawk in 2005, and she tried to hide her unease as the dye runoff turned the water into what looked like blood.

The red she saw in Drowning Bear Creek had come from the nearby dyehouse, where carpets got their colors. There, machines whirred as workers sloshed around in rubber boots in ankle-deep dyewater, reminding Martin of fishermen. The acrid odor made her eyes tear up.

A recent California transplant at the time, Martin recalled her initial culture shock.

“At a gut level, you know it’s not right. And unfortunately, when you try to raise the flag and everybody’s like, ‘Well, that’s just the way it is,’” Martin said in an interview.

“I became complacent.”

Like Shaw, Mohawk is based in northwest Georgia and is among the largest carpet companies in the world. The industry supported the entire community, employing someone in what seems like every family. Martin realized carpet was in the region’s DNA.

Martin said the chemical runoff was routine during her 20 years at Mohawk, which ended with her 2024 retirement. Sometimes, when the company dyed carpets blue, the water in the creek would be blue, too. One spill that turned the creek purple for a mile downstream killed thousands of fish, records show.

Mohawk’s attorney called such spills “rare instances” that were promptly reported and said there is no evidence any spills directly discharged PFAS.

In the dyehouse, what neither Martin nor the workers could detect were the colorless, odorless compounds also included in the wastewater: forever chemicals. Machines bathed the carpets in these soil-and-stain blockers, and what didn’t stick washed away.

For decades, Mohawk’s and Shaw’s mills sent PFAS-polluted wastewater through sewer pipes to the local Dalton Utilities plants for treatment that did not remove the chemicals. Much of the tainted water ended up in the Conasauga River.

Both Shaw and Mohawk said they operated in accordance with permits issued by Dalton Utilities. The utility said it takes direction from federal and state regulators, who have not prohibited PFAS in industrial wastewater.

The Conasauga watershed is filled with lush green pastures, creeks and tributaries that help fuel the water-hungry industry. The river’s waters emerge out of Georgia’s Blue Ridge Mountains and eventually flow southwest, past Dalton, Calhoun and Rome, and then into Alabama.

Residents downriver from the mills didn’t know about the chemicals running through their towns. But the industry’s top leaders did.

PFAS is a catchall term for a group of thousands of related synthetic compounds also known as fluorochemicals. They have been fundamental to the carpet business since the 1970s, as market demand for stain resistance transformed the industry, and carpet makers began buying millions of pounds. In the mid-1980s, the introduction of DuPont’s Stainmaster, accompanied by a successful marketing blitz, further established these products as essential.

Neither DuPont nor its related chemical companies that supplied PFAS provided comment for this story.

The carpet industry used so much PFAS that Dalton’s mills became the largest combined emitters of the chemicals among 3M’s U.S. customers, according to a 1999 internal 3M study that looked at 38 industrial locations.

Before 3M had pulled Scotchgard, leading to Bob Shaw’s showdown in the spring of 2000, both Shaw Industries and Mohawk had been privy to inside information that PFAS were accumulating in human blood. Bob Shaw did not respond to requests for comment.

In late 1998 and early 1999, 3M held a series of meetings with carpet executives to disclose its blood-study research, according to 3M’s internal meeting notes from court records.

“When we started finding the chemical in everybody’s blood, one of the biggest worries was Dalton, because we knew how sloppy they were,” Rich Purdy, a 3M toxicologist who alerted the EPA to his company’s hiding of PFAS’ dangers, said in an interview.

Notes by a 3M employee from a January 1999 meeting said Mohawk executives did not express grave concerns about the revelations. “No real sense of Mohawk problem/responsibility,” 3M noted. “If it’s good enough for 3M, it’s good enough for Mohawk.” Mohawk’s attorney said of the meetings over two decades ago that 3M assured the company its chemicals were safe.

At another meeting that January, Shaw executives were “concerned but quiet,” with one executive expressing he “felt plaintiffs’ attorneys would be involved immediately,” according to 3M’s notes. Shaw Industries maintains it learned of the concerns about Scotchgard at the same time everyone else did.

In follow-up letters to top executives with Shaw and Mohawk later that month, 3M noted the company’s efforts were guided by the idea that reducing exposure “to a persistent chemical is the prudent and responsible thing to do” while emphasizing current evidence did not show human health effects.

“We trust that you appreciate the delicate nature of this information and its potential for misuse,” the letters said. “We ask that you treat it accordingly.”

3M then asked for access to Shaw and Mohawk mills to see if they were handling the chemicals safely, records show. Those internal reports, produced in 1999, would fault how carpet companies handled PFAS products, exposing workers and the environment, according to court records.

The next year, 3M and EPA announced concerns about Scotchgard.

The day of the announcement, the director of EPA’s Chemical Control Division sent an email to his colleagues and counterparts in other countries calling the key ingredient in Scotchgard an “unacceptable technology” and a “toxic chemical.” The email said the compound should be eliminated “to protect human health and the environment from potentially severe long-term consequences.”

3M declined an interview request. In a statement, the company said it has stopped all PFAS manufacturing and has invested $1 billion in water treatment at its facilities. “3M has taken, and will continue to take, actions to address PFAS manufactured prior to the phase out,” the company said.

In 2000, the year 3M announced it was pulling Scotchgard, Mohawk logged more than $3.4 billion in net sales. Shaw Industries reported $4.2 billion.

EPA would not issue its first provisional health advisories for nearly another decade. Absent federal guidance, the carpet industry could legally continue to use these products.

Despite accumulating health and environmental concerns, federal law at the time did not let EPA ban any chemical without “enormous evidence” of harm, said Betsy Southerland, a former director of the agency’s water protection division who spent over three decades there.

“So we were really hamstrung at the time,” said Southerland, who has become a critic of EPA.

At Mohawk, Lisa Martin was not an executive making decisions about PFAS, she said, but her time at the company weighs on her still.

“Unfortunately, I later learned that there are more people that I worked with that were aware of it,” she said. “They were aware of it and didn’t do the things they should have done.”

Years into her tenure, the athletic and inquisitive Martin began getting sick and feeling lethargic. Her doctor said she’d grown nodules on her thyroid, a gland that is a key part of the immune system and which studies have shown forever chemicals can harm.

She had no family history of thyroid issues. It was a mystery to her.

Cozy relationship

Inside the Dalton headquarters of the Carpet and Rug Institute, industry executives and the local water utility conferred in 2004 about EPA’s growing scrutiny.

For several months, EPA representatives had negotiated with Dalton Utilities and the carpet industry through the institute, its influential trade group, over gaining access to their facilities to test the water. Mohawk and Shaw were using DuPont’s Stainmaster and other products, which also contained forever chemicals akin to Scotchgard’s older formulation.

Still, federal regulators worried these compounds were exhibiting similar harmful properties. Dalton Utilities and the carpet industry were uneasy about welcoming in government officials. Companies could not be guaranteed confidentiality and feared test results could lead to “inaccurate public perceptions and inappropriate media coverage,” records show.

The public utility and the carpet industry chose to resist.

Their close ties went back years. Carpet executives have long sat on Dalton Utilities’ board, appointed by the city’s mayor and city council. Fueled by the growth of the carpet industry, Dalton Utilities’ fortunes rose with the industry’s success.

At the carpet institute’s 2004 annual meeting, officials with carpet and chemical companies convened to discuss the EPA’s increasingly aggressive posture. Shaw’s director of technical services, Carey Mitchell, addressed his colleagues. He was blunt. No company would allow testing.

“Dalton Utilities has said not no, but hell no,” Mitchell said, according to notes made by a 3M attendee. Mitchell did not respond to requests for comment.

In response to questions for this story, Dalton Utilities declined an interview request but said it and the carpet industry “have always operated independently of one another” and that the EPA testing request was informal.

The carpet institute declined an interview request, sending a written statement instead.

“The CRI’s conduct was and continues to be appropriate, lawful, and focused on our customers, communities, and the millions of people who rely on our products every day,” institute President Russ DeLozier said, adding: “Today’s carpet products reflect decades of progress, and The CRI members remain committed to moving forward responsibly.”

The EPA stiff-arm was the latest run-in between Dalton Utilities and federal regulators.

A public water utility’s obligation, above all else, is to ensure clean drinking water. Dalton’s utility had previously gone to criminal lengths to deceive regulators.

In the early 1990s, Dalton Utilities’ staff traced a drop in oxygen levels in its wastewater treatment to stain-resistant chemicals from carpet mills, the utility’s top engineer at the time, Richard Belanger, said in an interview. While the utility didn’t know about PFAS then, something in these chemicals was impacting its ability to process the wastewater, he said. Rather than clamping down on industry, according to Belanger, his bosses ordered him to manipulate pollution figures the utility reported to government regulators.

“I was told, OK, make this work,” Belanger, now retired, said.

In June 1995, EPA investigators interviewed Belanger. He told them Dalton Utilities’ program to clean industrial pollutants was “a sham.” The treatment was so poor, the smell of carpet chemicals carried throughout the utility’s plant, and local creeks were often “purple and foamy,” according to investigators’ notes from the interview.

Two months later, agents with the FBI and EPA raided Dalton Utilities’ offices.

Federal prosecutors charged the utility with violating the Clean Water Act by falsifying wastewater reports, which concealed the full extent of the carpet industry’s pollution. The case did not address PFAS specifically, which was not yet a pollutant of concern for EPA. Dalton Utilities pleaded guilty in 1999 and was fined $1 million. Its CEO was removed.

The utility was also put under federal monitoring in 2001 to ensure it was making key changes to protect the water supply and agreed to pay a $6 million penalty.

The era of legal troubles with the federal government was pivotal, the utility said, adding it “has remained committed to avoiding the issues that led to those proceedings” and is transparent with regulators.

Around the same time, emerging data showed the fluorochemicals used in carpets caused cancer in rats.

The carpet institute’s then-president, Werner Braun, forwarded the rat study to several carpet and chemical executives in a 2002 email, calling the findings a “troubling issue,” records show. Braun, now in his 90s, was unable to comment for this story due to his health, his wife said.

In preparing to respond to Braun, a 2002 email shows DuPont officials planned to explain that Stainmaster didn’t contain the type of PFAS that was then EPA’s focus. The next year, DuPont would tell carpet companies the opposite, acknowledging the chemical was indeed in Stainmaster. DuPont maintained in later legal proceedings it wasn’t aware until 2003 that Stainmaster contained the chemical.

Despite its success in fending off EPA testing, the industry faced a mounting challenge, and the carpet institute focused on shoring up its influence and image.

At a meeting in the spring of 2004 attended by top executives, the carpet institute decided to solicit donations from company employees for its political action committee “in an effort to submit friendships, gain access, and say thank you to legislators,” according to meeting notes.

Later that year, PFAS made news in a high-profile legal case involving DuPont. The class-action lawsuit brought by residents in West Virginia claimed their water had been contaminated by a nearby chemical plant that used PFAS. Although DuPont said the settlement did not imply legal liability, it agreed to pay $70 million and to establish a health monitoring panel. Some two decades later, Braun was shown the rat study email during a legal deposition.

“I wouldn’t necessarily call it a red flag but a flag, you know, that you might want to be aware of,” he said.

Only years later did people downstream begin to learn the toll.

The river brought the poison

When Marie Jackson’s goats started dying about a year ago, nobody could explain why. Jackson saw it as just another sign something was wrong with her land.

Marie and her mother, Faye Jackson, have lived on their 12 acres near Calhoun for decades. Today they keep mostly to themselves, inseparable, equal parts bickering and loving.

Most days, Marie makes the short drive down a gravel road, Jackson Drive, to her mother’s house to check on her. She tends to Faye’s chickens, mows her grass and drives her to doctor’s appointments. Behind their homes is a rolling stretch of grassy pasture where their cattle graze — and the goats did as well, she said, until they all died.

Past a curtain of trees on the far end of the pasture lies the Conasauga.

Marie, 50, spent her childhood playing and swimming in the muddy river with rocks on the banks that made a good fishing spot. The Jacksons now know the water that sustains their homestead, about 15 miles downstream from Dalton, is contaminated.

Tests of the river by the AJC found levels of what was once a key ingredient in Scotchgard at more than 30 times the proposed EPA limits for drinking water. Tests of Faye’s drinking water well by the AJC and the city of Calhoun found PFAS just under these federal health limits.

Calhoun city officials used that health standard to guide a program designed to address contaminated wells. A 2024 legal settlement between the city and the Southern Environmental Law Center included a condition to test local water. As of August, 30% of private wells tested had levels above the health limit.

Because Faye’s test was just below the cutoff, she does not qualify to receive a filtration system.

Uncertainty about the chemicals continues to permeate every aspect of the Jacksons’ lives. They fear PFAS are behind their declining health. They fear their drinking water. They fear for the health of the cattle and chickens they raise; and for the health of those who may eat them.

“I know they’ve got it in their systems,” Faye said.

Even Marie’s memories are filled with second-guessing. Idyllic scenes of her childhood are now overshadowed by recollections of foam on the river and dead fish. She blames the mills.

The Jacksons, like generations of northwest Georgians, relied on the carpet industry. Both of Marie’s parents worked in the mills: Faye with yarn machines and her dad in the dyehouse. Marie would end up working in carpet, too.

Everyone suspected the work was dangerous. Faye said she’d get headaches from the strong chemical smells. The hours were long. But with the risk came a steady wage.

“Around here, you have to understand the people, that’s all we know, right? That’s all we’ve ever been around,” Marie said, fidgeting with her plastic water bottle. “It’s like you don’t think. It’s routine. You go in, you know your job, you do your job, you go home.”

Faye’s failing health eventually forced her to stop working. Today she drinks water she buys from the store.

In 2022, Faye’s husband, Robert, died after struggling with several illnesses. She now wonders whether decades of PFAS exposure was to blame. And Marie has nodules growing on her thyroid.

The Jacksons long suspected they had forever chemicals in their blood. With their consent, the AJC commissioned testing last fall and the mother and daughter finally learned the truth. Their PFAS levels were above the safety threshold outlined by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

“They’ve poisoned us,” Faye said.

Among the highest ever recorded

In 2006, the carpet industry and Dalton Utilities faced a new dilemma.

University of Georgia researchers were testing the Conasauga for PFAS, and early results seen by carpet companies showed high levels. Shaw Industries began conducting its own tests, which confirmed UGA’s results: PFAS coursed through the river.

As Georgia’s scientists worked on their PFAS study, the majority of outside experts on an EPA advisory panel determined the PFAS associated with DuPont’s Stainmaster was ” likely to be carcinogenic.” In 2005, the year prior, EPA and DuPont settled a claim that the chemical company failed to report for decades what it knew about the risks. At $10.25 million, it was then the largest penalty ever obtained under a federal environmental law. DuPont did not admit liability.

The university’s study, eventually published in 2008, made headlines. The UGA researchers reported PFAS levels in the Conasauga were “among the highest ever recorded in surface water” like a river or a lake. Not just in the United States, but worldwide.

Journalists from a local newspaper also began asking questions about the study and the earlier decision by the utility and the industry to deny regulators access for testing.

A Chattanooga Times Free Press reporter was “hot on the trail” of a story, wrote Denise Wood, at the time a Mohawk environmental executive and Dalton City Council member, in a February 2008 email to Dalton Utilities CEO Don Cope.

One of the university researchers told the paper that UGA’s test results were “staggeringly high.” Cope did not respond to requests by the AJC and AP for an interview, and Wood declined to comment.

At the carpet institute, officials rushed to create a crisis management team, internal records and emails show. The industry downplayed the UGA study and broader concerns about PFAS.

“In our society today, it is absolutely known that you report the presence of some chemical and everybody gets all up and arms,” the institute’s head, Braun, told reporters.

UGA’s study had an impact. The EPA returned in 2009. Unlike before, the agency now had provisional health advisory limits for certain PFAS compounds, offering regulators some enforcement authority.

This new scrutiny would uncover a major source of pollution along the Conasauga.

On the edge of Dalton, the Loopers Bend “land application system” occupies more than 9,600 acres on the river’s banks. The public utility had long hosted hunts for wildlife at the forested site, which is crisscrossed by a network of 19,000 sprinklers that sprayed PFAS-laden wastewater for decades.

For years, the site’s design allowed runoff to leak into the river, according to EPA’s former water programs enforcement chief. The wastewater was so poorly filtered the ground felt like walking on “shag carpet” due to all the fibers, the EPA official, Scott Gordon, said in an interview. He noted gullies cut by wastewater led directly to creeks and the river.

Because Dalton Utilities distributed the treated wastewater over land instead of discharging it into the river directly, it didn’t need a federal Clean Water Act permit. After EPA inspected and saw the conditions, the agency ordered the local utility to apply for one. The state, however, had approval power in Georgia and rejected the application, saying the permit wasn’t necessary.

Today, Loopers Bend remains a significant source of PFAS in the Conasauga.

The EPA worked with Dalton Utilities to upgrade the site starting in 1999, but it would be years before the agency would require testing of the Conasauga’s water.

In 2009, testing reports submitted by Dalton Utilities to EPA confirmed what the UGA research had already shown: Forever chemicals had infiltrated the region. In addition to river and well water, deer and turkey taken from Loopers Bend had PFAS in their muscles and organs.

Dalton Utilities said that levels of PFAS in its wastewater and the compost it provided to enrich soil for farmers and homeowners were not a health risk. PFAS were everywhere and a “societal problem,” and not one Dalton Utilities could solve, the utility’s lawyer wrote the EPA in 2010.

Nonetheless, the utility agreed to restrict its compost distribution and test wastewater from a quarter of its industrial customers annually.

As later testing showed, the chemicals would persist for years.

A health reckoning

Why is the doctor calling? Dolly Baker wondered as she rinsed the hair of a client at her salon “Dolled Up” in Calhoun. Dr. Dana Barr’s number had popped up on her cellphone.

Baker had taken part in a 2025 Emory University study of northwest Georgia, where she was one of 177 people who had their blood tested. Now one of the study’s lead scientists was on the phone.

Barr, an analytical chemist with epidemiological experience, had been mailing study participants about the results. When she saw Baker’s test data, she dialed her phone.

Baker, a lifelong Calhoun resident now in her 40s, had PFAS levels hundreds of times above the U.S. average.

“I don’t want to alarm you, but we’re just trying to figure out what can be causing this,” Barr told her, Baker later recalled. “I suggest you talk to your doctor and let them know that there are certain cancers that can come into play later.”

Baker was speechless.

She walked back to her wash station and slowly started rinsing her client’s hair again, quietly processing what this all meant. How did she have such high levels? Her mind raced.

What was she supposed to do about the forever chemicals in her body?

“Unfortunately, there is no easy answer,” Baker said Barr told her.

Emory tested Baker’s water and hair products, but the tests came back low. Almost a year after learning her blood test results, Baker is no closer to knowing why her levels are so high.

She said she’s frustrated by the lack of action and leadership, especially after years of testing and community meetings to discuss the problem.

“You know, people go in other countries to help them get clean water,” Baker said, “and do we have clean water?”

Barr, who spent years at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studying environmental toxicants, realized there was too little data to grasp the problem in northwest Georgia. She helped launch Emory’s study to understand the extent of contamination in human blood.

Three out of four residents tested by Emory had PFAS levels that warrant medical screening, according to clinical guidelines from the National Academy of Sciences.

“People in Rome and in Calhoun tended to have higher levels of PFAS than most of the people in the U.S. population,” Barr said.

Mohawk and Shaw say they stopped using older fluorochemicals around 2008. These were known by chemists as “long-chain” or C8 because each had eight or more carbon atoms on their molecular chains. Scotchgard, Stainmaster and Daikin’s Unidyne have since been reformulated without these C8 compounds.

Chemical manufacturers made new “short-chain” or C6 versions with six carbon atoms. Daikin U.S. Corp. said in a statement it “is committed, as it always has been, to regulatory compliance, evolving PFAS science, and global standards.”

Despite the chemical variations, short-chain PFAS had the stain-busting and water-repellant traits of the older chemicals. Scientists in the 2010s also expressed concerns that the newer formulations might carry similar environmental and health risks. Some began calling them “regrettable substitutes.”

After saying it got out of PFAS completely in 2019, Shaw has struggled to remove the chemicals from its facilities. The company said the compounds have so many applications they appear elsewhere in the machines and processes it takes to produce carpet.

“You can’t just say you stopped using them and you’re done,” said Ballew, Shaw’s vice president for environmental affairs.

She said the company installed filters at some mills and sleuthed out PFAS sources from its supply chain to remove them. Shaw developed a testing technology and shared it with suppliers so they could do the same, offering it as an example of strong corporate citizenry from a company with roots in the region.

“Shaw didn’t quit looking, and that’s what I’m really proud of,” Ballew said. “That’s the story. It’s not how long it took us to get here.”

Worries, but few answers

Down the road from Baker’s hair salon, Dr. Katherine Naymick operates a private medical practice. She’s practiced in Calhoun since moving there in 1996.

Naymick’s office sits in a small strip mall off Calhoun’s main road — a tidy, white-walled office decorated with retro medical equipment. She’s been mystified that many of her young patients’ thyroid glands had just “quit on them.” Similarly, she said her patients also had higher rates of endocrine cancers than the national average.

Doctors have few tools to address patient concerns, as the understanding of these chemicals’ links to health effects is still evolving. One resource is guidance the National Academy published in 2022 for physicians, which cites the “alarming” pervasiveness of PFAS contamination.

That guidance recommended doctors offer blood testing to patients who live in high exposure areas. The panel also cautioned the results could raise questions about links to possible health effects that cannot be easily answered.

People like Dolly Baker are at higher risk of kidney or other cancers, and thyroid problems, research shows.

When Naymick started in Calhoun, chemical manufacturers knew about the potential dangers of forever chemicals, but the public did not. The doctor said she did her best to treat her patients while feeling powerless to understand why they were so sick.

Then studies began to emerge in the 2000s showing high levels of forever chemicals in the Conasauga. In the 2010s, the first large health studies tied PFAS to issues with childhood development and the immune system.

Naymick enrolled in environmental medicine training, which focuses on patients’ exposure to contaminants, among other factors. Through study, Naymick gained tools to investigate the area’s heavy industrial footprint she long suspected. She started looking for clues, including blood tests, that might help explain her patients’ problems. Soon she zeroed in on forever chemicals.

In 2025, Dr. Barr’s group at Emory used Dr. Naymick’s clinic to draw blood. Naymick now thinks all her patients should get tested because of their high chance of exposure. But insurers rarely cover PFAS tests, and many of her clients can’t afford the hundreds of dollars they cost.

As they wait, the full extent of the human toll in northwest Georgia remains unknown.

The pollution continues

This past June, more than a hundred people crammed into a barn in Chatsworth, about 10 miles east of Dalton.

Law firms operating under the name PFAS Georgia had been testing properties across northwest Georgia.

Nick Jackson, one of the attorneys, stood up to address the crowd, which was eager to hear about the contamination in their midst.

“If you feel compelled to lift up your test results so that your neighbors could see, please feel free to do so at this time,” he said. At once, people raised signs displaying the levels found on their properties, many substantially above EPA health guidelines.

PFAS Georgia has filed numerous lawsuits against chemical manufacturers and carpet makers since last June. Today the group represents dozens of residents and farmers in northwest Georgia who allege their properties are contaminated with PFAS from the carpet industry. The wave of litigation is the latest development in a legal saga that began a decade ago.

In 2016, the eastern Alabama town of Gadsden filed the first of a series of municipal drinking water lawsuits against the carpet industry, accusing the mills upriver of contaminating its drinking water more than 100 miles away.

Three years later, Rome filed its own lawsuit against the carpet industry, chemical companies and Dalton Utilities. The city’s water, drawn downriver from Dalton, had tested at over one-and-a-half times the EPA’s health advisories at the time. Rome estimated a new water treatment plant would cost $100 million, to be paid for by a series of steep rate increases.

After several years of bitter litigation, Rome reached a series of settlements with carpet and chemical companies and the utility for roughly $280 million. None admitted liability.

For many, the lack of state and federal PFAS regulations means the courts are their only chance for accountability.

Georgia environmental officials have done little to regulate forever chemicals beyond drafting drinking water limits on two types of PFAS, deferring to their federal counterparts. The Trump administration’s EPA has said it intends to remove drinking water limits finalized by the Biden administration for some forever chemicals and is delaying limits on others until 2031.

EPA said it is working on better PFAS detection methods. “EPA is actively working to support water systems who are working to reduce PFAS in drinking water,” an agency spokesperson said in a statement.

In a statement, Georgia EPD pointed to testing it has done throughout the state. If PFAS is found above health advisory levels, the agency said it works to ensure safe drinking water is available.

Last year, several northwest Georgia legislators proposed a state bill that would have shielded carpet companies from PFAS lawsuits. The lead sponsor, state Rep. Kasey Carpenter, R-Dalton, said legal action should target chemical makers, not carpet companies. The bill failed.

Carpenter said he was not aware of the evidence showing the carpet industry knew of PFAS’ potential health risks and will consider it when he reintroduces the bill this year. He said, ultimately, he wants EPA to fix the contamination.

“There needs to be some kind of federal deal where money’s dumped in for cleanup. That, to me, is a solution,” Carpenter said.

The pollution continues. Dalton Utilities, in its own recent lawsuit against carpet and chemical companies, said PFAS applied long ago at the sprawling Loopers Bend land application system will continue to spread for the “foreseeable future.” The suit estimated PFAS contamination cleanup would likely exceed hundreds of millions of dollars.

“The contamination that exists today is the result of the carpet industry’s use and application of PFAS and PFAS-containing products, purchased from chemical suppliers,” the utility said.

Sludge spread by local municipalities to fertilize farms and yards over decades has pushed the crisis past the banks of the river and has heightened fears among some people over contamination in the local food supply.

PFAS Georgia said it has collected more than 2,600 samples of dust, soil and water from hundreds of properties. The group said it has detected PFAS at levels exceeding EPA limits in over half of its water samples. No such limits exist for dust or soil, but the sampling has found the compounds at high levels in both, particularly in the dust inside people’s homes.

“There’s nothing like northwest Georgia,” the group’s testing expert, Bob Bowcock, said. “I don’t know how we’re going to begin to tackle it.”

Last year, Lisa Martin, the retired Mohawk manager, received her results from the Emory study. Her blood tested higher than most Americans for a type of PFAS used by the carpet industry.

After she moved to Calhoun decades ago to work in carpet, Martin’s health declined. She has struggled with a suppressed immune system and long COVID. There were the nodules on her thyroid. She began to suspect PFAS.

“What are the odds with my health that I’m going to live to old age?” said Martin, 64.

Martin said she struggles with guilt from years of silence when she worked at Mohawk. Like many of her neighbors, she also wrestles with a sense of betrayal.

“How many people have lost their health,” she asked, “because somebody made a decision not to do anything?”