On a below-freezing day in January, Pennsylvania House Speaker Joanna McClinton delivered food to a West Philly home just minutes from her district office and listened as Sheila Alexander discussed the patchwork of care she has created for herself.

Alexander, 67, who struggles to get around on her own, explained that she depends on family often but uses a Medicaid-funded home health aide who helps her in the evening — especially when she needs to get up the steep stairs in her home.

McClinton is advocating for the aides who care for Alexander — and the rest of the roughly 270,000 Pennsylvania workers who make up the home care industry — to earn a higher wage.

Pennsylvania’s home healthcare workers are among the lowest-paid in the region at an average $16.50 per hour, resulting in what the Pennsylvania Homecare Association has called a crisis point for home care, as more and more workers leave the field and seniors struggle to find help. And it’s a crisis that may only deepen in future years, as one in three Pennsylvanians are projected to be 60 or older by 2030.

It’s an issue that McClinton, a Philadelphia Democrat who became House speaker in 2023 when her party took a one-seat majority, has had to contend with in her own life.

McClinton’s 78-year-old mother lost one of her favorite aides because of low pay, she said. The aide had cared for McClinton’s mother for a year, until the aide’s daughter got a job at McDonald’s that paid $3 more an hour. At that point, McClinton said, her mother’s aide realized just how low her pay was.

McClinton said she helps her mother when she can, but she only has so many hours in the day and needs assistance when she’s at the Capitol.

“Many of my colleagues are just like myself, supporting parents who are aging and trying to make sure that they have all the necessities so that when I’m in Harrisburg I’m not thinking, ‘Oh, my God, how’s my mom going to eat or how’s she going to have a bath,’” McClinton said. “It’s because of home health aides and the folks assigned to her that she’s able to thrive. But she’s not unique.”

Until recently, McClinton had taken a more hands-off approach compared with some previous House speakers who would use their position as the top official to push through their personal agendas. Now, she is taking a more active role in pushing for the issues she cares about most, with special attention to the home care wage crisis.

Home care workers are often paid through Medicaid, which provides health services to low-income and disabled Americans and is administered at the state level. Pennsylvania has not increased how much it reimburses home care agencies, resulting in all of the surrounding states paying higher wages to home care workers, including GOP-controlled West Virginia and Ohio.

Describing her leadership approach with a slim majority as “pragmatic,” McClinton says her goal is to find common ground to raise the wages for home healthcare workers between Republicans and Democrats, on an issue that impacts residents across all corners of the state.

“We just have to really coalesce and build a movement so that we see things get better and that there’s more care,” she said. “Because when there’s more care, there’s less hospitalization, there’s less ER trips, there’s more nutrition.”

Better pay at Sheetz

Stakeholders recount dozens of similar stories of aides leaving to work at amusement parks, Sheetz stores, or fast-food restaurants because the pay is better. What’s more: Some home health aides will choose to work in a nearby state where wages are all higher than those paid in Pennsylvania.

Cathy Creevey, a home health aide who works for Bayada in Philly, made $6.25 when she started working in the field nearly 25 years ago. Now, she makes just $13.50. She has watched countless colleagues quit to take higher-paying jobs elsewhere, resulting in missed shifts and seniors that go without the care they need.

“We have patients that are 103, 105, and when that aide doesn’t show up their whole world is turned upside down because sometimes we’re the only people that they see to come in, to feed them, to bathe them,” Creevey said.

While Creevey said she stays in the work because she cares about her patients, she said the long hours and low pay are difficult.

Fewer and fewer people being willing to take on the jobs means seniors going without care or being forced into already understaffed nursing homes throughout the state.

“Participants are waiting for care that isn’t coming,” said Mia Haney, the CEO of the Pennsylvania Homecare Association.

Haney said she hoped McClinton’s advocacy will help drive the issue heading into the next budget season.

“She has a wonderful opportunity to really influence her peers, but also raise awareness and education about how meaningful and critical these services are,” Haney said.

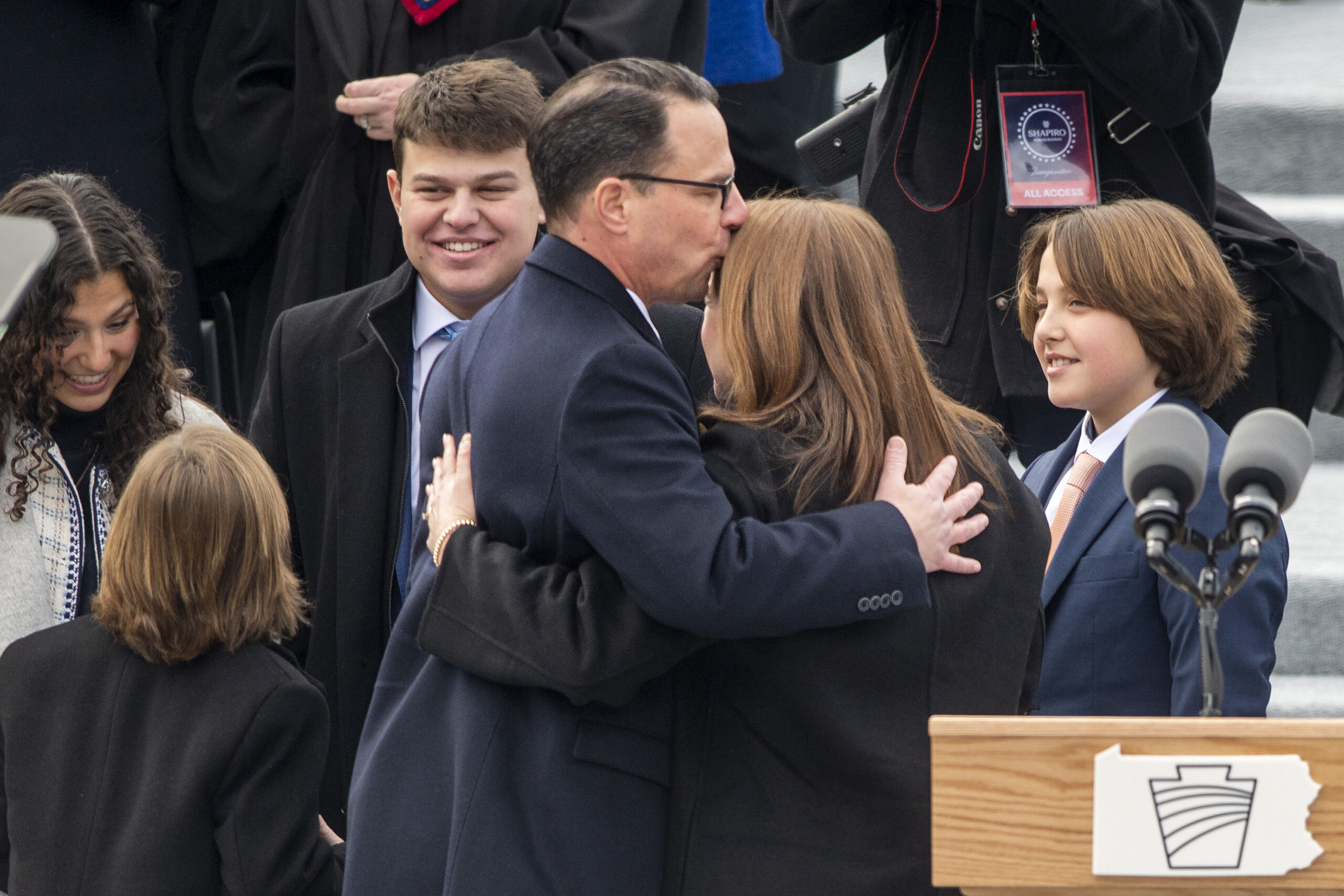

In addition to McClinton’s advocacy, 69 House Democrats sent a letter to Gov. Josh Shapiro earlier this month, calling for more funding for the struggling industry just as Shapiro is set to make his 2026-27 budget proposal next month.

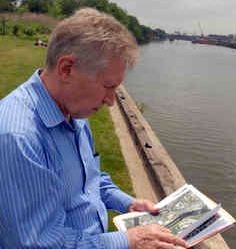

Older Pennsylvanians prefer to “age in place,” or stay in their homes where they remain connected to their communities, said Kevin Hancock, who led the creation of a statewide 10-year strategic plan to improve care for the state’s rapidly aging population.

“Nursing facilities and hospital services get a lot of attention in the space of older adult services, but it’s home care that really is the most significant service in Pennsylvania,” Hancock said. “The fact that it doesn’t seem to warrant the same type of attention and same type of focus is pretty problematic.”

Home care remains popular in Pa.

The fight to increase dollars for home care workers has been an uphill battle in Harrisburg even with the speaker’s support.

More Medicaid dollars go to home care services than any other program in Pennsylvania due to its popularity among Medicaid recipients, Hancock said. Meanwhile, its critical care workers — a majority of whom are women or women of color — still make low wages for often physically and emotionally demanding work.

A study by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services last year determined that a 23% increase would be necessary for agencies to offer competitive wages, but the state’s final budget deal did not include it. (The final budget deal did provide increases to direct aides hired by patients, which represent about 6% of all home care workers in the state.)

Home care agencies are asking Shapiro to include a 13% reimbursement rate increase in the 2026-27 budget, which equates to a $512 million increase for the year. The 13% ask, Haney said, was a “reasonable and fair” first step in what would need to be a phased approach to reaching competitive wages.

But neither Shapiro nor Senate GOP leadership has committed to any increases in the forthcoming budget.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Shapiro said the governor understood the need and cited his support for limited increases in last year’s budget and for a proposed statewide minimum wage increase to $15 per hour. (Previous efforts by the Democratic House to increase the state’s minimum wage have stalled in the GOP-controlled Senate.)

Senate Majority Leader Joe Pittman (R., Indiana) said his caucus will put the state’s “future financial stability” before all else. Pennsylvania is expected to spend more than it brings in in revenue this year, setting the stage for yet another tense budget fight.

“While we’ve seen Democrats continually push for more spending within the state budget year after year, any increases require thoughtful consideration as to the impact on hardworking taxpayers of Pennsylvania,” Pittman added.

McClinton, however, was cautiously optimistic that something could be done this year, even as she placed the onus on Senate Republicans, rather than Shapiro.

“We’ve seen Republicans refusing to work, refusing to resolve issues, that’s not acceptable,” McClinton said. “I’ve seen an unwillingness from Republicans to resolve these issues.”

Republicans, she said, should come to the table because staffing shortages harmed their constituents in rural Pennsylvania even more than it harmed hers in Philly.

“We have to get our heads around the fact that we have the lowest reimbursement rates in our area,” McClinton said in an interview after visiting two patients in her district. “We have to make the investment now. We have lots of needs. We have lots of priorities, but we can balance them.”