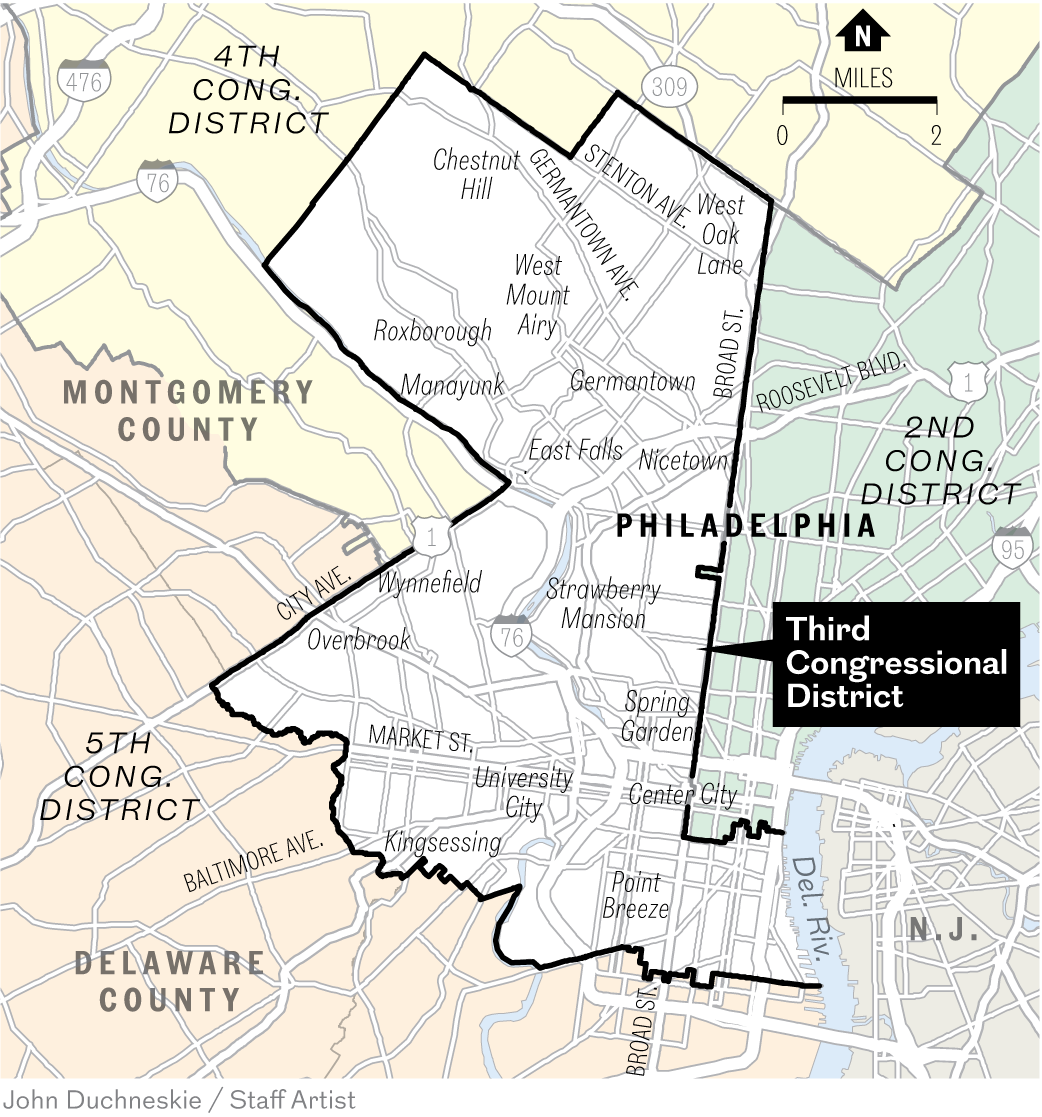

A normal, healthy weight for me was 120 pounds. In the late 1990s, before addiction reshaped the course of my life, I was a model — someone whose world revolved around silhouettes, styling, and self-expression through fashion.

My metabolism kept me effortlessly consistent in size, my confidence steady, my presence bold. In Philadelphia, style carried currency, and I spent mine generously. I was known — and crowned — as the “Queen of Fashion,” a title that suggested a life stitched together with glamour, ease, and admiration.

I hired two of my very own fashion designers, and they made leather tops and pants specifically for me. I shopped at the most exquisite stores on South Street for shoes, clothes, and designer sunglasses. I kept my hair done and went to a nail salon in Center City on a regular basis — all part of the architecture of how I showed up.

I looked healthy, controlled, and admired, even as addiction was quietly taking hold. I looked like someone who had mastered the runway. No one knew that soon I would be fighting a battle that fashion couldn’t tailor, metabolism couldn’t manage, and praise couldn’t heal.

No one knew the story would shift from being known for how well I wore clothes to how bravely I rebuilt the body inside them.

By 2001, that admiration extended beyond aesthetics. I worked as therapeutic support staff — a job that demanded attentiveness, emotional intelligence, and care. I delivered it well. My clients felt seen. My coworkers felt supported. Respect followed me into rooms before I even sat down.

On the surface, my life looked like momentum — until prescription opioids quietly stepped in and dismantled the foundation beneath it.

I became what many called “functional” — a person whose addiction was masked by productivity, routine, and public reliability. But functionality is not the absence of illness. It is often the art of hiding it. And I practiced that art for nearly a decade.

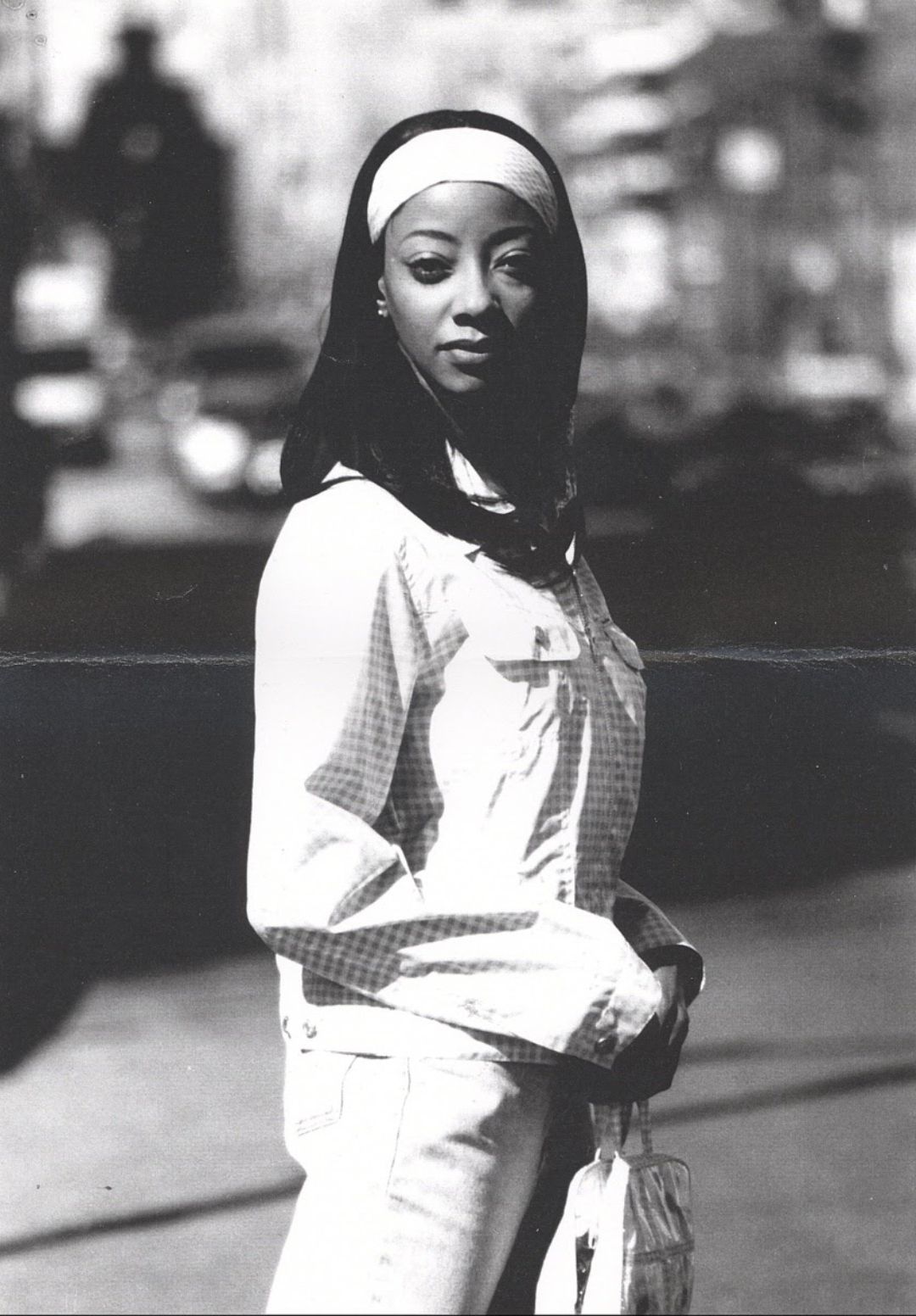

I went from a size 5/6 to a 1/2 very quickly — a dramatic drop that unfolded faster than most narratives could keep up. The weight disappeared. The applause appeared. The concern stayed absent. People praised the result without recognizing the cause.

Compliments met me at the door before questions ever did: You look amazing. You’re so small now. What are you doing?

But I wasn’t doing anything admirable. I was enduring something dangerous. The shrinking they celebrated was not transformation. It was toxicity — a body under neurological attack, nutritional depletion, depression, and a decade-long prescription opioid addiction that pulled more from me than pounds. It eventually cost me my hearing.

As my body grew smaller, the praise grew louder. At the same time, as I declined medically, physically, mentally, and emotionally, the world grew quieter about the part that mattered. They applauded the appearance of wellness while I was privately collapsing.

Skinny equaled praise to them.

To me, it was evidence that I was fading.

In 2010, recovery finally became my rescue. It demanded rebuilding, not shrinking — a process slower, quieter, and far less visible than what the world celebrates.

As my brain healed from the damage of long-term opioid use, my body began reclaiming the signals addiction had silenced: appetite, rest, regulation, safety, nourishment. The pounds I regained were not a reversal of progress. They were proof of it.

There was no applause for that rebuilding. No celebration for the return of sleep, nourishment, or neurological stabilization. The world didn’t honor restoration because restoration didn’t look like reduction. It looked like progress that challenged how we measure wellness.

At times, rebuilding invited commentary that echoed the same shallow math that once praised me: You used to be so small. Are you OK? The irony was painful. The same shrinking that was celebrated when it was harming me was questioned when it was saving me.

Today, the cultural conversation around weight has grown louder, faster, more pharmaceutical, and more celebrated. Medications that promise shrinking have become shorthand for “wellness” in the public imagination.

But in recovery communities — including those quietly healing in our own region — weight gain often signals restoration. It signals life returning to a body that nearly didn’t survive the war addiction waged on it.

Bodies in crisis don’t need applause for shrinking. They need care for surviving. And bodies in recovery don’t need shame for rebuilding. They deserve compassion.

Recovery doesn’t always show up as loss. Sometimes it shows up as strength. Sometimes it shows up as nourishment. Sometimes it shows up as life returning to places addiction tried to erase.

If you or someone in your life is walking the path of recovery, understand this: Healing does not always match what society rewards. Progress may look unfamiliar or misunderstood. A body that is stabilizing is not disappearing — it is reclaiming itself.

Culture may applaud reduction. Recovery teaches something different: renewal, resilience, and the quiet work of staying alive.

That work matters. And it deserves dignity and recognition.

Chekesha Lakenya Ellis is a certified peer recovery specialist. The Burlington County resident uses Facebook to raise awareness about addiction and recovery.