Carl W. Schneider, 93, of Philadelphia, retired longtime attorney at the old Wolf, Block, Schorr, & Solis-Cohen law firm, former special adviser to the Securities and Exchange Commission, visiting associate professor at what is now the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, writer, poet, mentor, and volunteer, died Thursday, Dec. 18, of pneumonia at Pennsylvania Hospital.

Mr. Schneider was an expert on corporate, business, and securities law, and he spent 42 years, from 1958 to his retirement in 2000, at Wolf, Block, Schorr, & Solis-Cohen in Philadelphia. He was adept at handling initial public offerings and analyzing stock exchange machinations, and he became partner in 1965 and chaired the corporate department for years.

Although he did not plan to specialize in securities law after graduating from Penn’s law school in 1956, Mr. Schneider told the American Bar Association in 1999: “I found this type of work to be challenging, gratifying, stimulating, and educational.”

He spent most of 1964 on leave from the law firm as a special adviser to the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Division of Corporation Finance in Washington. His recommendations to SEC officials regarding its public-offering process, disclosure system, civil liability rules, and arbitration procedure, many of which were ahead of their time, eventually led to modernization and reforms in the administration of federal securities laws. “I was cast in the role of the constructive critic,” he said in 1999.

He chaired committees for the Philadelphia and American Bar Associations and was active in leadership roles with the American Law Institute and other groups. He clerked for Supreme Court Justice Harold H. Burton and Judge Herbert F. Goodrich of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit for two years after graduating from law school.

He also taught classes as a visiting associate professor at Penn’s law school and lectured extensively elsewhere on the continuing legal education circuit. “I am aware of two personality traits that have shaped my career,” he said in 1999, “a need to fix things and a love of teaching.”

He spent the 1978-79 school year as head of Penn’s Center for Study of Financial Institutions and said in 1999 that he would have taught full time had he not enjoyed his legal work so much. “I was a practitioner,” he said, “and I tried to give my classes useful training to do what most practitioners do.”

Mr. Schneider wrote, cowrote, and edited dozens of scholarly articles, books, and pamphlets, including the celebrated Pennsylvania Corporate Practice and Forms manual in 1997. He also penned poetry, and used this stanza to open a chapter about boilerplate clauses in the Pennsylvania Corporate Practice and Forms manual:

“The ending stuff gets little thought/Like notice, gender, choice of laws/If badly done you may get caught/With a provision full of flaws.”

He volunteered with what is now Jewish Family Service, the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia, Abramson Senior Care, and Congregation Rodeph Shalom. He mentored countless other lawyers and students, and agreed in 1972 to a request by The Inquirer’s Teen-Age Action Line to be interviewed in his office for a high school student’s research project.

“He was often described as brilliant, humble, a dry wit, and a great listener,” his family said in a tribute. “He gave everyone he spoke to the same time, attention, and respect.”

He was quoted often in The Inquirer and lectured about legal matters at conferences and panels. He earned several service and achievement awards and said in 1999: “I suppose I am one of those compulsives who cannot see something in the world important to him that is broken without feeling the need to repair it.”

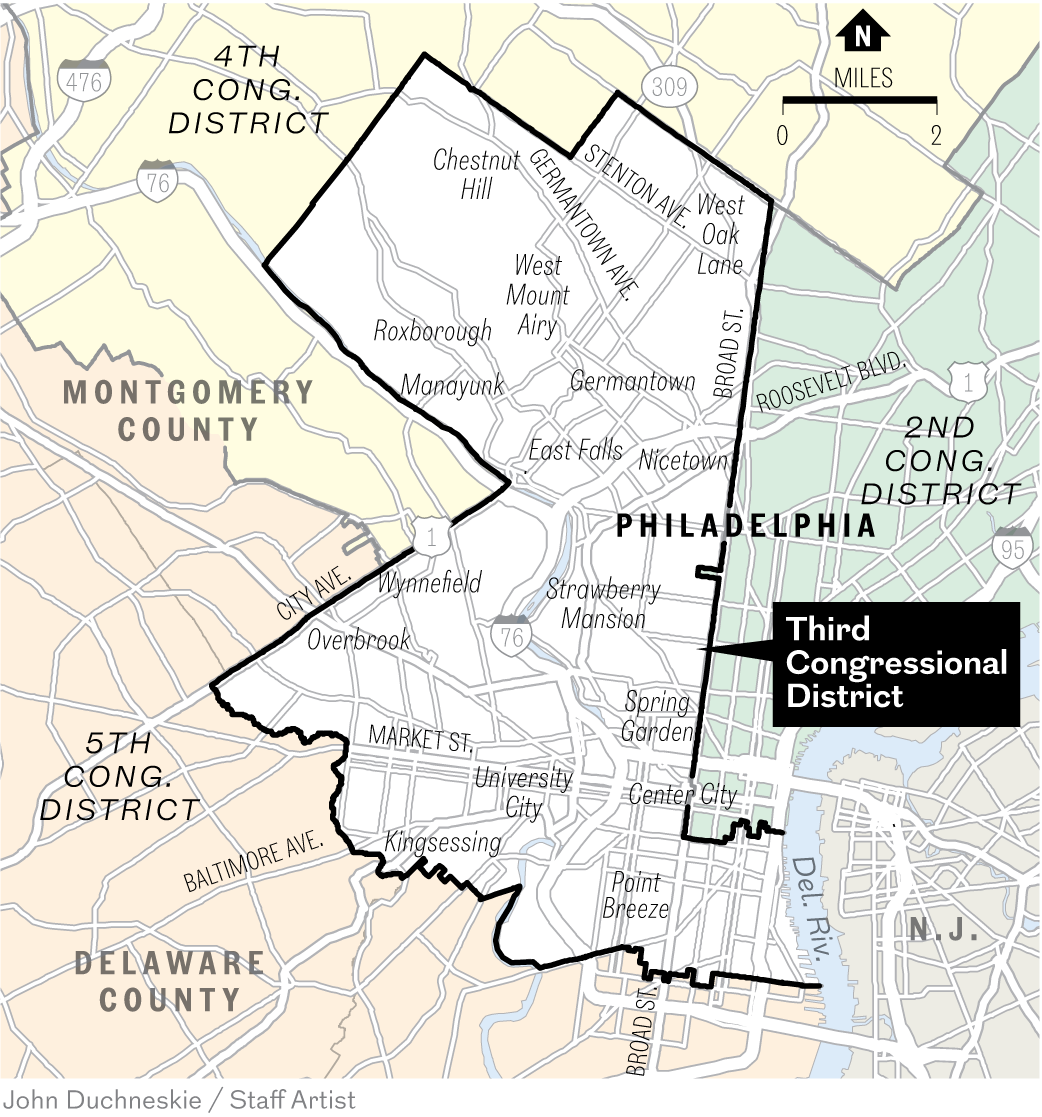

Carl William Schneider was born April 27, 1932, in the Wynnefield section of Philadelphia. His family later moved to Elkins Park, Montgomery County, and he graduated from Cheltenham High School in 1949.

He knew he wanted to be a lawyer, like his father and grandfather, when he was young and said in a 2014 video interview at Penn that school was his favorite place. He earned a bachelor’s degree at Cornell University in 1953 and served on the law review at Penn.

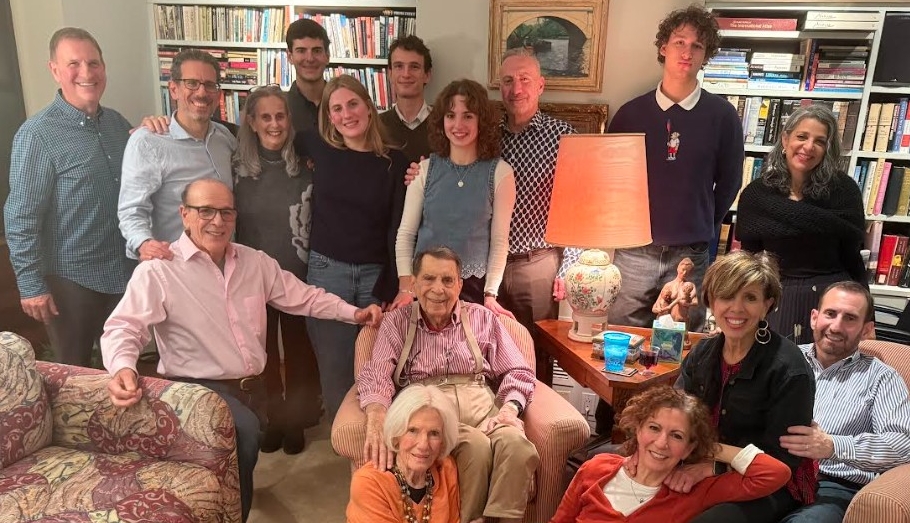

He met Mary Ellen Baylinson through a mutual friend, and they married in 1957. They had sons Eric, Mark, and Adam and a daughter, Cara, and lived for years in Elkins Park. He and his wife moved to Center City in 2005.

Mr. Schneider enjoyed reading, bird-watching, photography, swimming, tennis, and springtime strolls through Rittenhouse Square. His favorite song was “The Gambler” by Kenny Rogers.

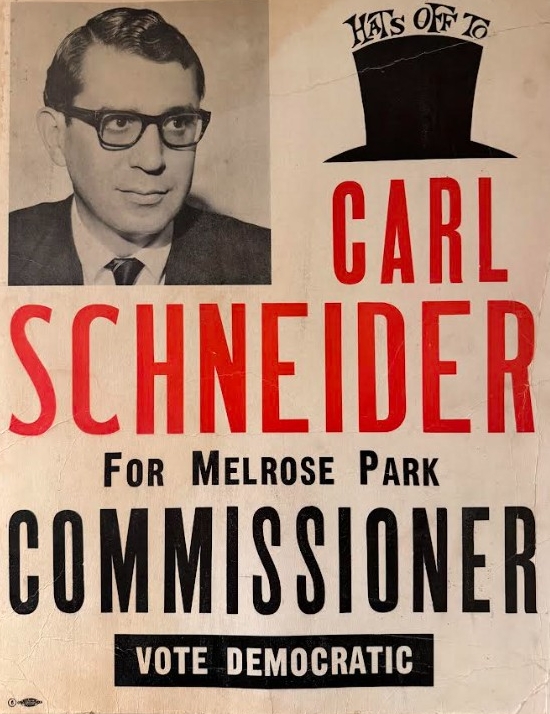

He collected old-fashioned scales, spent quality time with family and friends on Long Beach Island, N.J., and drove cross-country on a family road trip in a motorhome he nicknamed Herman. He ran unsuccessfully for commissioner in Melrose Park in the 1960s.

He made sure to be home every night for dinner and drew smiley faces inside the capital C when he signed his name. “He never judged, never overreacted,” his daughter said.

His son Adam said: “He was a gentle man but forthright and direct.” His son Mark said: “He had a moral code on how to live a life and never deviated from it.”

His son Eric said: “He left the world a better place.”

In addition to his wife and children, Mr. Schneider is survived by three grandchildren; a sister, Julie; and other relatives.

Services were held Monday, Dec. 22.

Donations in his name may be made to Congregation Rodeph Shalom, 615 N. Broad St., Philadelphia, Pa. 19123.