A year ago, leaders of Family Practice & Counseling Network feared their health clinic, which has served low-income Philadelphians for more than 30 years, wouldn’t survive past June.

The clinic was part of Resources for Human Development, a Philadelphia human services agency that a fast-growing Reading nonprofit called Inperium Inc. had acquired in late 2024.

As a federally qualified health clinic since 1992, the clinic had received an annual federal grant, higher Medicaid rates, and other benefits.

But federal rules prohibited the clinic from continuing to retain that status and those benefits under a parent company. That meant Family Practice & Counseling Network had two options: close or spin out into a new entity that would reapply to be a federally qualified clinic.

“We had to figure it out,” the organization’s CEO Emily Nichols said in a recent interview.

At the time, the organization’s three main locations had 15,000 patients. They are “very underserved, low-income people that deserve good healthcare,” she said.

Thanks to $9.5 million in financial and operational support from the University of Pennsylvania Health System, a new legal entity took over the clinics in July. They now operate under the tweaked name, Family Practice & Counseling Services Network, and without the federal status.

“Penn allowed us to survive,” Nichols said.

Still in a precarious position

The nonprofit, with its name now abbreviated as FPCSN, remains in a precarious position.

Because of the corporate change, the $4.2 million annual grant that Family Practice had been receiving through RHD had to be opened up for other applicants under federal law. FPCSN applied but won’t find out until March the result of the competition.

Natalie Levkovich, CEO of the Health Federation of Philadelphia, a nonprofit that supports community health centers in Southeastern Pennsylvania, expressed confidence that the clinic will regain the funding, which helps cover the cost of caring for people who don’t have insurance.

“FPCSN is a well-run, well-regarded, well-supported health center that has an established, high-functioning practice in multiple locations,” Levkovich said. The clinic received letters of support from all the other federal clinics in the area, she said.

In addition to the grant, other key benefits of being a federally qualified health center — the status the clinic had for 33 years — are receiving medical malpractice insurance through the federal government and enhanced Medicare and Medicaid rates.

In return, federally qualified clinics have to accept all patients, including people without insurance. The insurance mix of FPCSN’s patient population is about 60% Medicaid, 20% uninsured, 10% Medicare, and 10% commercial, Nichols said.

Also, half of a federal clinic’s board members have to be patients at the clinic. FPCSN has three main locations, in Southwest Philadelphia, on the western edge of North Philadelphia, and in the West Poplar neighborhood. Its revenue in fiscal 2025 was $31 million.

During the past year, 55 FPCSN staff members have left, leaving 140 employees still at the organization, including 16 nurse practitioners who provide the primary care. The departures may have contributed to a decline in the number of patients seen to 13,500 last year, compared to 15,000 the year before, Nichols said.

Why Penn helped FPCSN

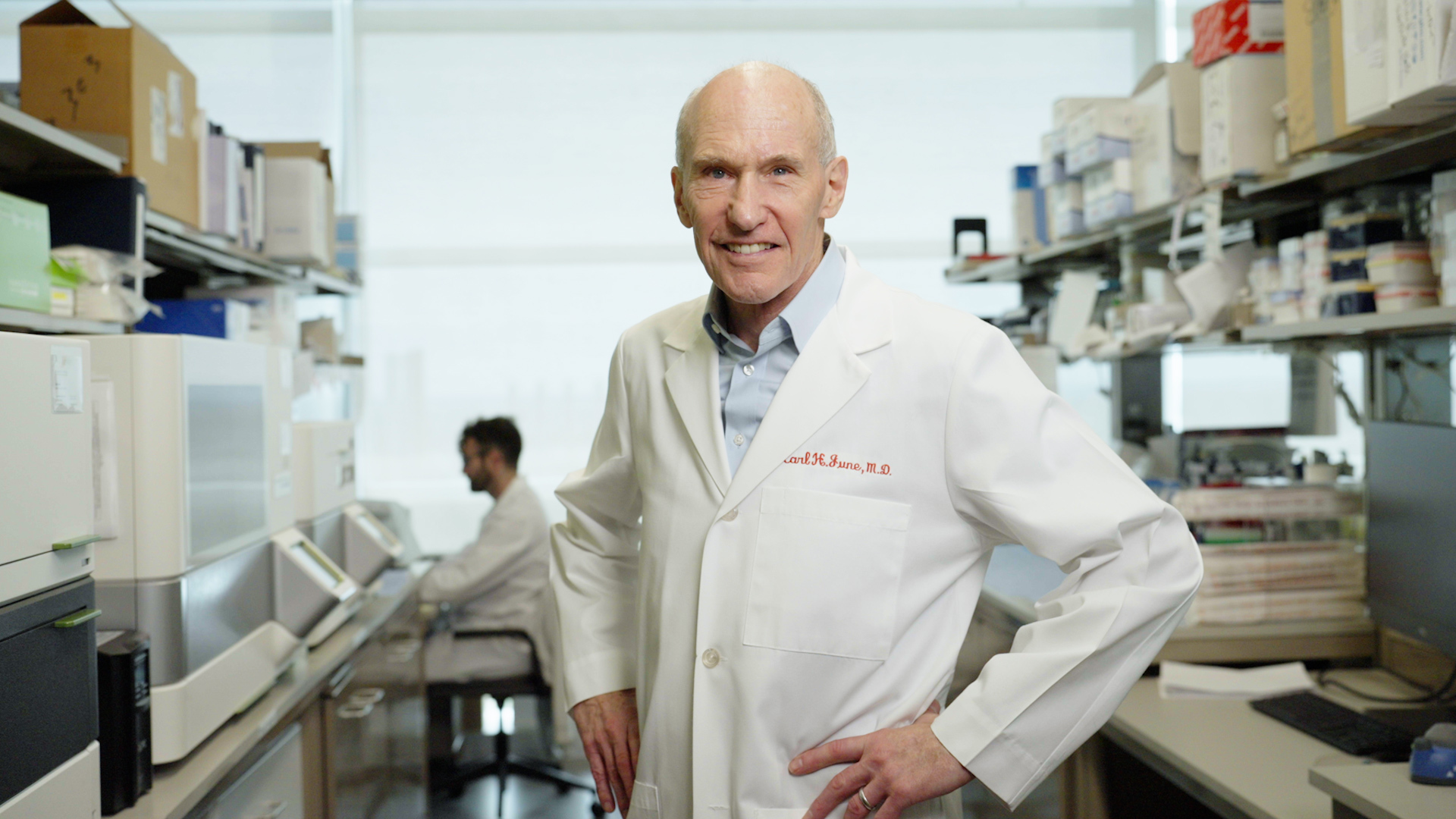

Federally qualified health centers form the core safety net in Philadelphia and across the nation, said Richard Wender, who chairs Family Medicine and Community Health at Penn, which had a longstanding relationship with RHD’s clinics.

Under contract, Penn family practice physicians were providing prenatal care to 400 pregnant patients at the clinics that would have closed abruptly at the end of June if Penn hadn’t provided support. “We wanted them to be able to continue to take care of the patients that they were taking care of,” Wender said.

The money from Penn helped pay startup costs for the new entity and bridged the period until FPCSN was able to secure new contracts with insurance companies.

Penn also didn’t want the clinic’s patients showing up in its already busy emergency departments for basic care. “That adversely affects their health because it’s not a good place to get preventive care,” he said.

But it was important to Penn that there was a pathway back to federal clinic status. “We feel as optimistic as we can,” Wender said.

Wender and Nichols credited Kevin Mahoney, CEO of Penn’s health system, with the preservation of FPCSN’s services for low-income Philadelphians by throwing his full support behind the effort.

“You have to have a CEO, a leader in your health system, who understands that this is the responsibility of large academic health centers,” Wender said.