Spotlight PA is an independent, nonpartisan, and nonprofit newsroom producing investigative and public-service journalism that holds power to account and drives positive change in Pennsylvania. Sign up for our free newsletters.

HARRISBURG — Rents are soaring, homelessness is rising, and homeownership is out of reach for many families in Pennsylvania. As the state grapples with a serious housing shortage and affordability dominates the national political conversation, Gov. Josh Shapiro is preparing to release a long-awaited plan to tackle the crisis.

The plan, first announced in late 2024, will draw on months of outreach to advocates, developers, and local officials. Supporters hope it will offer a clear path forward and build momentum around proposals that can win support in Pennsylvania’s politically divided legislature. But significant obstacles stand in the way.

“The housing crisis has risen to the level such that none of the four caucuses can ignore it,” said Deanna Dyer, director of policy at Regional Housing Legal Services, a nonprofit law firm.

The housing shortage is a nationwide problem, but Pennsylvania has been particularly slow to build new units. The shortfall leaves families squeezed by rising costs, pushes recent graduates to take jobs in other states, and makes it harder for companies to expand.

Other states are passing laws to loosen local zoning restrictions and encourage new development — despite often fierce opposition from groups representing local governments.

Similar efforts in Harrisburg have not yet gained traction, although more lawmakers are exploring solutions, said State Rep. Lindsay Powell, a Democrat representing Pittsburgh who cochairs the House Housing Caucus.

“Pennsylvania has an opportunity to really push itself forward here.”

Falling behind

Underlying Pennsylvania’s housing crunch is the law of supply and demand.

Between 2017 and 2023, the number of households in Pennsylvania grew by 5%, according to a recent report from Pew Charitable Trusts, a think tank. Over the same period, local governments issued only enough building permits to increase the state’s housing stock by 3.4%.

That left Pennsylvania ranked 44th out of 50 states on the rate of housing built.

“The most important driver of affordability is whether there are enough homes for everyone,” said Alex Horowitz, Pew’s director of housing policy.

High demand for existing units, combined with a lack of new supply, gives landlords more leverage to raise rents and drives up house prices, Horowitz said.

“The shortage is what is causing housing to get so expensive right now.”

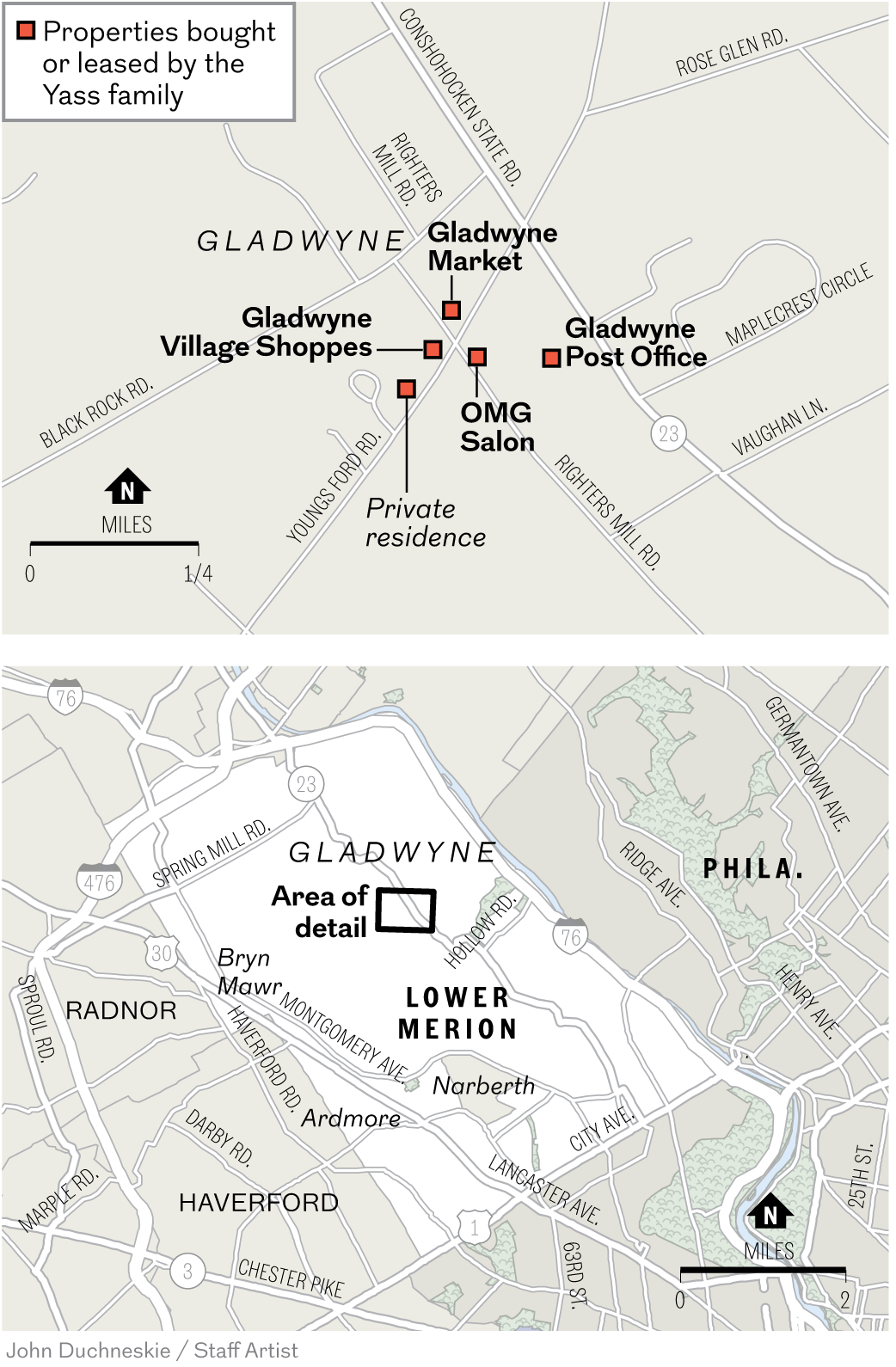

The problem is not spread evenly across the state. Costs have risen the most in areas with growing populations that have not added enough housing, including the Philadelphia suburbs, Northeastern Pennsylvania, and cities like Harrisburg, York, and Lancaster.

To keep up with the demand, state officials estimate, Pennsylvania needs to build 450,000 units by 2035 — a 70% increase in new construction.

In September 2024, Shapiro signed an executive order directing the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development to create a statewide plan to increase the supply of housing, and to review the effectiveness of existing programs. The executive order also requires the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services to conduct a separate review of policies to address homelessness.

“We don’t have enough housing, the cost of housing is going up, and the housing we do have is getting older and is in need of more repairs,” Shapiro said, announcing the plan.

Since then, DCED has received feedback from almost 2,500 people and organizations, and held 15 listening sessions across the state, a spokesperson said.

A draft was due to be submitted to the governor’s office in September, according to the executive order, but the details have not yet been made public.

Zoning headaches

In roundtables and written feedback, state officials heard about problems small and sweeping. One issue came up repeatedly, according to interviews with participants and a review of hundreds of pages of written recommendations obtained through the state Right-to-Know law: To build more housing, Pennsylvania needs to change local zoning rules that stifle new construction.

There are a number of ways the state could approach this. Many municipalities reserve most of their land zoned residential for single-family homes. Pennsylvania could allow apartment buildings on land currently zoned for commercial use, or near public transit, or legalize accessory dwelling units, like backyard cottages and granny flats.

Changes like these would require revising the municipal planning code, the state law that gives local governments authority over land-use decisions.

These changes would also make it easier to address rising demand for smaller units, as the average household size falls and more people live alone.

Any attempt to change zoning laws, however, will likely face strong opposition from groups representing Pennsylvania’s municipalities. They argue that local governments know their communities best and should retain control over decisions about land use. They also say the focus on zoning overlooks other factors contributing to the housing shortage, like the rising cost of construction materials and supply-chain disruptions.

Municipal zoning laws are “often scapegoated” as the culprit for a lack of affordable housing, Logan Stover, director of policy and legislative affairs at the Pennsylvania State Association of Boroughs, told Spotlight PA in a statement.

In October, a senior Shapiro staffer working on the housing plan told a local group in Lancaster the plan would focus on “incentives rather than mandates,” with a points-based system to give communities that adopt pro-housing policies priority for state funding. Communities with policies that restrict new development could be disqualified, he said.

At least six states — including California, Massachusetts, and New York — have already created incentive programs, which vary in design and enforcement mechanisms.

These efforts have not proven as effective as broader statewide zoning changes, said Horowitz, the Pew researcher.

“States that tried that early on didn’t see the supply response,” he said.

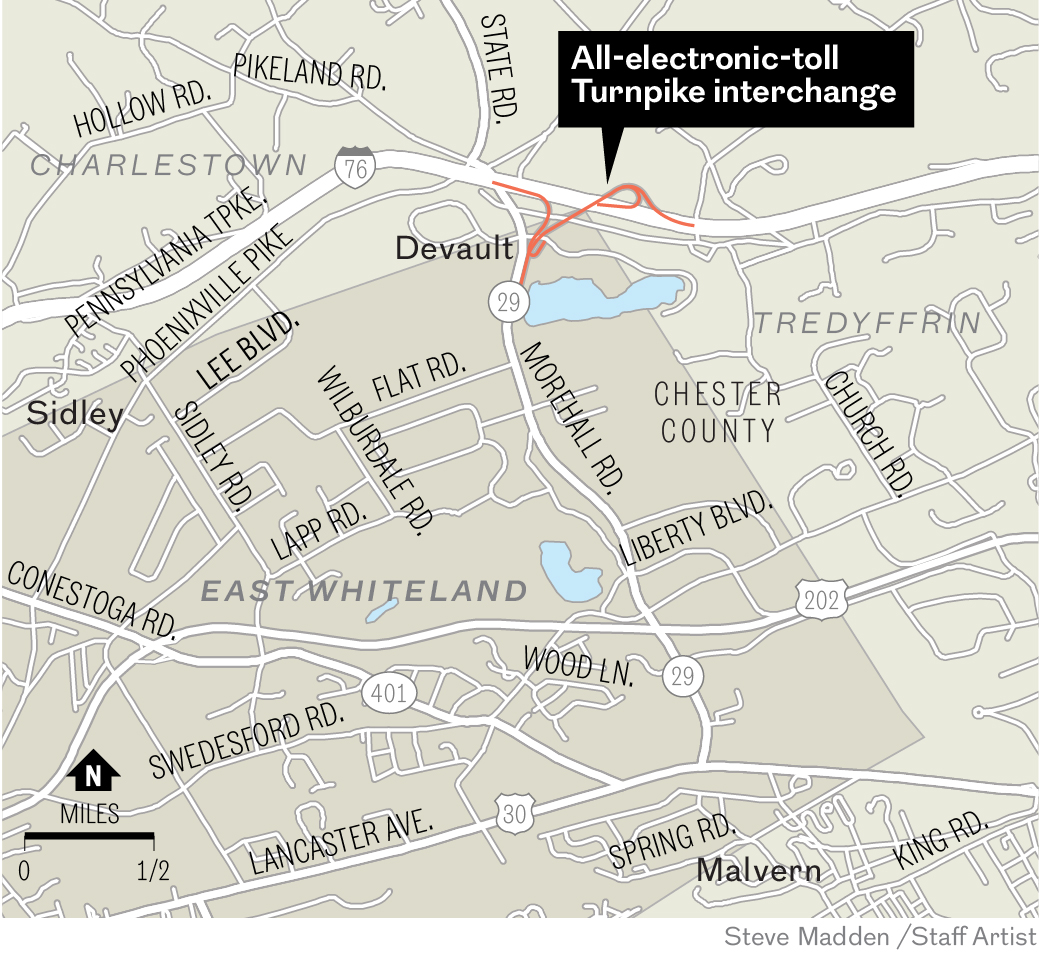

The state plan will also likely focus on how to simplify and speed up local permitting processes, which can delay construction with time-consuming paperwork and unpredictable outcomes. Streamlining state permitting has already been a major focus for Shapiro.

Focus on preservation

Pennsylvania doesn’t just need to build more housing — it also needs to help people stay in their current homes, state officials heard.

Groups that provide free legal services to low-income residents say there has been a dramatic increase in the number of people seeking help with evictions, foreclosures, and similar problems. In 2024, legal aid providers said, housing made up a third of all their cases — the single largest category.

They also urged state officials to keep pushing to seal eviction records in some cases, which Shapiro has said he supports but would require changing state law.

Another common thread was the need for a permanent source of funding to help low-income homeowners with repair costs. The state has some of the oldest housing stock in the U.S.; more than 60% of houses were built before 1970.

Investing in home repairs is broadly popular but has proven politically challenging.

In 2022, the state legislature agreed to spend $125 million in federal pandemic aid to create a new home repair program.

Demand was overwhelming: Some counties were able to take applications only for a few days and thousands of homeowners ended up on wait lists. The program was widely praised for its flexibility, which allowed administrators to help homeowners who would not have been able to get help from other programs, although some counties ran into administrative difficulties.

The program was created with bipartisan support, but efforts to continue it with state funding in 2023 and 2024 were unsuccessful. Last year, Shapiro proposed $50 million for a new, rebranded repair program, but the money didn’t make it into the final budget deal.

Looking ahead

Although Shapiro could make some changes through executive action, many of the suggested policy goals would require legislation.

Housing has proven to be an issue that can cut through political divides in Harrisburg, where Democrats control the state House and the governor’s mansion while Republicans hold a majority in the state Senate.

In recent years, lawmakers have agreed to a series of funding increases for a grant program to build and repair affordable housing. They also supported Shapiro’s proposal for a major expansion of a program that gives older and disabled residents a partial refund on their rent and property tax payments. The changes, which took effect in 2024, made more Pennsylvanians eligible and boosted the value of the rebates.

Between July 2024 and June 2025, more than 25 states passed legislation aimed at increasing the supply of housing, according to an analysis by the Mercatus Center, a libertarian think tank. Pennsylvania was not one of them, although lawmakers in both chambers have unsuccessfully introduced bills to loosen zoning requirements.

More recently, lawmakers from both parties have circulated proposals that echo some of the recommendations floated during the outreach for Shapiro’s housing plan. Republicans who control the state Senate say addressing the housing shortage will be a “key focus” for their caucus this year.

State Sen. Joe Picozzi (R., Philadelphia), chair of his chamber’s Urban Affairs and Housing Committee, plans to introduce legislation that would offer grants to local governments that work with developers to build housing near centers of employment. “To qualify, communities must show they are committed to smart housing policies — like updating zoning, faster permitting processes, or preparing development-ready land,” according to a legislative memo.

Picozzi and other Republican senators also want to extend property tax abatements for new development and create a “pre-vetting” system for housing plans to simplify local approvals.

This year represents a real opportunity to make progress on the housing shortage, said State Rep. Jared Solomon, a Democrat representing Northeast Philadelphi,a who has sponsored several pieces of legislation aimed at adding more housing.

“We’re all seeing the same thing in our neighborhoods — we all know we have to be proactive about it,” Solomon said.

BEFORE YOU GO… If you learned something from this article, pay it forward and contribute to Spotlight PA at spotlightpa.org/donate. Spotlight PA is funded by foundations and readers like you who are committed to accountability journalism that gets results.