Irene Blair was expected to have another six to eight months to live in June, after her pancreatic cancer rapidly advanced to stage 4 less than a year after her initial diagnosis.

A new drug being tested in clinical trials around the world, including at Penn Medicine’s Abramson Cancer Center, was the 59-year-old grandmother from Newark, Del.’s best hope for more time.

The drug belongs to a class of pharmaceuticals long considered the holy grail of cancer research. It is a KRAS inhibitor, capable of blocking a protein that fuels an especially deadly cancer. Only 13% of pancreatic cancer patients are still alive five years after their diagnosis, the highest mortality rate of all cancers.

Called daraxonrasib, the drug is not considered a cure. But the results emerging from clinical trials point to the first major advancement in decades for a devastating cancer usually caught in late stages. Former Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse last week disclosed in a blunt social media post that he was recently diagnosed with metastasized, stage-four pancreatic cancer and is “gonna die.”

In recent months, the federal government has sped up the review timeline for the drug made by California-based company Revolution Medicines, Inc., based on early clinical trial results.

Across 38 patients in a phase 1 trial, the drug appeared to double the survival time for at least half of patients compared to standard chemotherapy, from roughly seven months to 15.6 months.

“In pancreatic cancer, for too long, we haven’t had effective therapies beyond just chemotherapy,” said Mark O’Hara, Blair’s oncologist who leads multiple clinical trials testing KRAS inhibitors at Penn.

Blair started the therapy through a phase 3 trial in July. Within three weeks, her cancer-associated pain went away.

In October, her tumors looked stable or decreasing on scans. Her most recent December scan showed her cancer had not progressed.

Aside from occasional facial rashes, she feels normal. It’s a big improvement from how she felt previously on chemotherapy, which caused her to lose 35 pounds and become so weak she couldn’t walk.

The question now is how long the therapy can remain effective. Blair seeks extra time to “start living life.”

She officially retired from her job in real estate in May and wants to travel, with trips planned to see family in California and Florida.

Holidays have been especially hard for her.

“You just wonder, ‘Will I be here next year?’” she said.

How does the therapy work?

Cancer researchers have worked to design a drug targeting KRAS, a protein that acts like a “gas pedal” for cancer growth when mutated, since its discovery in 1982.

The mutant protein is like a pedal stuck in the down position, driving uncontrolled proliferation — which tumors thrive on. These mutations are found in a quarter of human cancers, mostly aggressive cancers of the pancreas, lung, and colon.

Scientists finally succeeded in 2021, when the first drugs capable of blocking KRAS were approved by the FDA for lung cancer. Dozens of KRAS inhibitors are now in various stages of development.

Daraxonrasib is one of the first tested for pancreatic cancer, a tumor type where nearly 90% of cases have these mutations. Also called a ‘pan-RAS inhibitor,’ it not only targets KRAS, but two other related proteins that drive cancer when mutated, HRAS and NRAS.

More than 90% of the 83 patients in a phase 1 trial saw their pancreatic cancer stall during treatment, and roughly 30% saw shrinkage.

While taking the drug, at least half of patients gained more than eight months before the cancer started progressing again.

The drug comes in the form of three pills, taken daily at home.

The most prevalent side effect is a rash — 91% of patients in a phase 1 trial experienced this symptom, with 8% having severe cases. It often shows up on the face or scalp and is similar to acne, O’Hara said.

Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and mouth sores are other common symptoms.

O’Hara said these are manageable with medications for most patients and still allow them to have a better quality of life than chemotherapy.

“I want to be able to give KRAS inhibitors to all my patients right now,” he said.

Looking forward

O’Hara runs multiple trials of KRAS inhibitors at Penn.

Some of them are testing the inhibitor as a treatment for patients with metastatic cancer after other options have stopped working. Another is evaluating its use in combination with chemotherapy as an initial approach.

“I’m looking for more tools to put in that toolbox, and I think this provides a new tool,” O’Hara said.

Ben Stanger, a gastroenterologist and scientist at Penn, has led experiments in mice that showed combining a KRAS inhibitor with immunotherapy may be more effective than using the former alone.

If this approach makes it into clinical trials as well, it could still take years to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the combination.

He believes KRAS inhibitors could be “a game-changer” for pancreatic cancer if approved, particularly if paired with other anti-cancer drugs.

“Goal number one would be to make pancreas cancer, instead of a death sentence, into a more ‘chronic’ disease that is treated over time,” he said.

The federal government has granted the drug Breakthrough Therapy and Orphan Drug designations.

In October, the drug was also one of the first selected for a new program that aims to accelerate review times for drugs from one year to as short as a month, potentially putting it on a faster path to approval.

Limited options

When Blair first started having back pain around May 2024, she thought it was a pulled muscle from kickboxing.

She put a heating pad on the back of her chair and went on with life.

After her father had a stroke that July, she got it checked out at the hospital where he was admitted.

A day later, she was diagnosed with stage 2B pancreatic cancer.

“My first thought is, ‘I’m dying,’” she said.

Had she been diagnosed earlier, she would have retired early, instead of worrying about saving money.

Instead, she spent her final working year undergoing surgery to remove part of her pancreas, spleen, and several lymph nodes, followed by 12 difficult sessions of chemotherapy.

When she finished her last session in March, Blair’s scans showed no evidence of the cancer. But by late April, her back pain returned.

Two months later, more scans showed that the cancer was now considered stage 4, as it had metastasized to her liver, forming 10 to 15 new tumors.

Her best option was to enter a clinical trial of daraxonrasib at Penn.

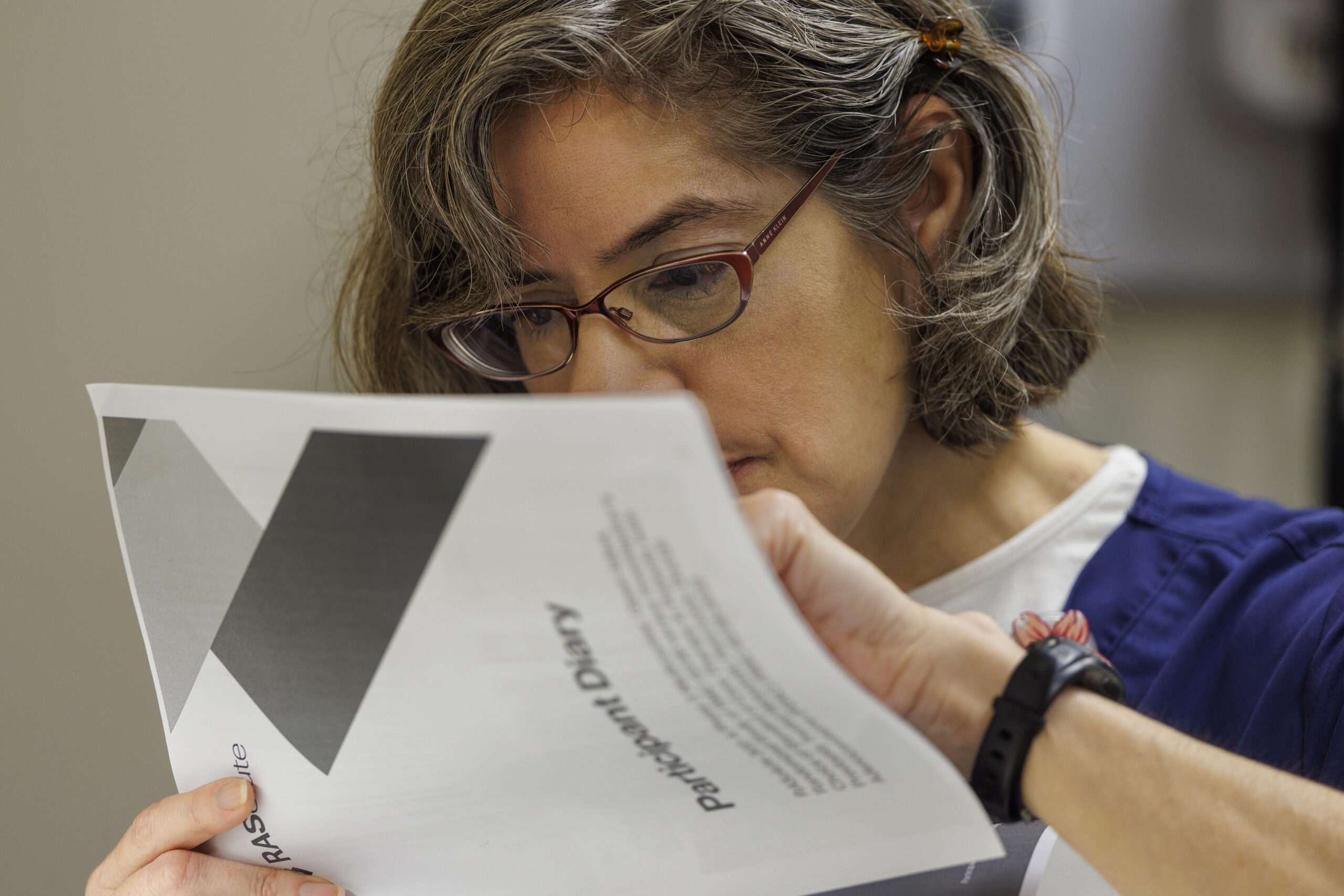

Much to her relief, she was chosen to receive the drug in July upon enrolling in a study in which half of patients are randomized to receive chemotherapy.

“It’s enabled me to start living again,” she said, but knows eventually the therapy will likely stop working.

In that case, doctors may try the standard chemotherapy — which usually works for three to four months — or test a different therapy based on her cancer’s genomic profile, O’Hara said.

For now, she described herself as “living scan to scan,” seeking as much time as possible with her son, grandchildren, and husband.

Blair’s next evaluation is in February. She hopes it shows her disease remains stable, and she can stay in the trial.

“The alternative, honestly, is death,” she said.