He had decided that the America he believed in would not make it if people like him didn’t speak up, so on a cool, rainy morning in the suburbs of Philadelphia, Jon, 67 and recently retired, marched up to his study and began to type.

He had just read about the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s case against an Afghan it was trying to deport. The immigrant, identified in the Washington Post’s Oct. 30 investigation as H, had begged federal officials to reconsider, telling them the Taliban would kill him if he was returned to Afghanistan.

“Unconscionable,” Jon thought as he found an email address online for the lead prosecutor, Joseph Dernbach, who was named in the story. Peering through metal-rimmed glasses, Jon opened Gmail on his computer monitor.

“Mr. Dernbach, don’t play Russian roulette with H’s life,” he wrote. “Err on the side of caution. There’s a reason the U.S. government along with many other governments don’t recognise the Taliban. Apply principles of common sense and decency.”

That was it. In five minutes, Jon said, he finished the note, signed his first and last name, pressed send, and hoped his plea would make a difference.

Five hours and one minute later, Jon was watching TV with his wife when an email popped up in his inbox. He noticed it on his phone.

“Google,” the message read, “has received legal process from a Law Enforcement authority compelling the release of information related to your Google Account.”

Listed below was the type of legal process: “subpoena.” And below that, the authority: “Department of Homeland Security.”

That’s how it began. Soon would come a knock at the door by men with badges and, for Jon, the relentless feeling of being surveilled in a country where he never imagined he would be.

Administrative subpoena

Jon read the message a second time, then a third. He didn’t tell his wife right away, worried she would panic. It could be fake, he thought, or a mistake. Or maybe, he feared, it had something to do with that four-sentence email he’d sent a prosecutor for the federal government.

Google hadn’t provided him a copy of the subpoena, but it wasn’t the conventional sort. Homeland Security had come after him with what’s known as an administrative subpoena, a powerful legal tool that, unlike the ones people are most familiar with, federal agencies can issue without an order from a judge or grand jury.

Though the U.S. government had been accused under previous administrations of overstepping laws and guidelines that restrict the subpoenas’ use, privacy and civil rights groups say that, under President Donald Trump, Homeland Security has weaponized the tool to strangle free speech.

For many Americans, the anonymous ICE officer, masked and armed, represents Homeland Security’s most intimidating instrument, but the agency often targets people in a far more secretive way.

Homeland Security is not required to share how many administrative subpoenas it issues each year, but tech experts and former agency staff estimate it’s well into the thousands, if not tens of thousands. Because the legal demands are not subject to independent review, they can take just minutes to write up and, former staff say, officials throughout the agency, even in mid-level roles, have been given the authority to approve them.

In March, Homeland Security issued two administrative subpoenas to Columbia University for information on a student it sought to deport after she took part in pro-Palestinian protests. In July, the agency demanded broad employment records from Harvard University with what the school’s attorneys described as “unprecedented administrative subpoenas.” In September, Homeland Security used one to try to identify Instagram users who posted about ICE raids in Los Angeles. Last month, the agency used another to demand detailed personal information about some 7,000 workers in a Minnesota health system whose staff had protested Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s intrusion into one of its hospitals.

“There’s no oversight ahead of time, and there’s no ramifications for having abused it after the fact,” said Jennifer Granick, an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union. “As we are increasingly in a world where unmasking critics is important to the administration, this type of legal process is ripe for that kind of abuse.”

Since the start of Trump’s second term, the ACLU has repeatedly heard from people whom Homeland Security targeted with administrative subpoenas, the organization says. It’s taken on three of those cases, but none of them, its attorneys say, illustrate how the agency has exploited that legal power better than Jon’s.

“This subpoena was part of a criminal investigation,” Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in a statement, noting that Homeland Security Investigations has “broad administrative subpoena authority” under the law.

McLaughlin didn’t say who was under criminal investigation, and the agency didn’t answer questions about Jon’s case or its broader use of administrative subpoenas.

In his living room on that fall day, Jon tried to make sense of the email.

He’d attended a No Kings rally last year, he said, and sent a few notes of criticism to lawmakers and maybe one to Trump’s administration during the president’s first term. But Jon, who worked in insurance, had never been arrested or questioned, he said, and his messages were written with the same “moderation” he displayed in the email to Dernbach, whose address he’d easily found on Florida’s bar association website.

Jon, who asked that the Post withhold his last name out of fear for his family’s safety, followed a link in the email that led him to a form letter. Google didn’t tell Jon what information the government officials wanted, but to keep them from getting it, he would have to file a motion in federal court and submit it to Google within seven days. Jon’s heart thudded in his ears.

He felt sick. Unsure of what to do, he told his wife.

“This is crazy,” she said. “How can our government be doing this?”

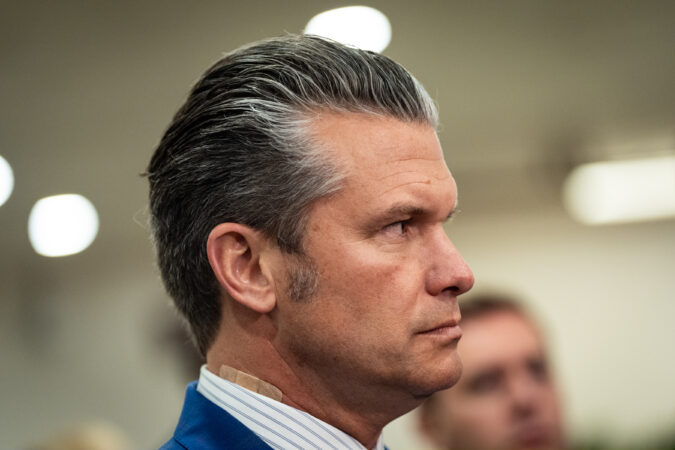

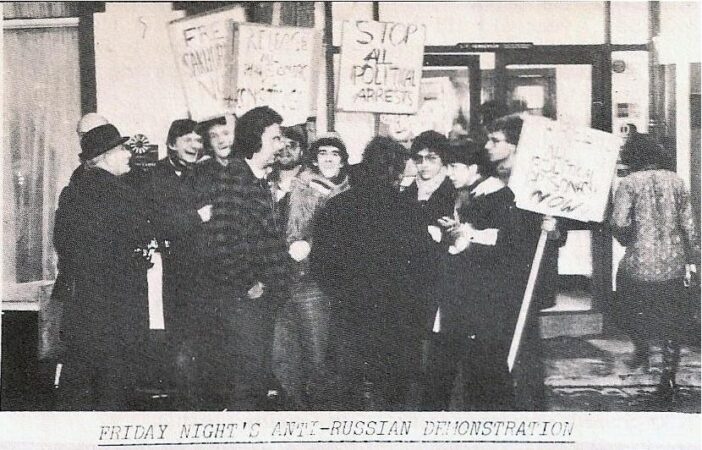

Born in England to a Jewish family, he grew up hearing the story of how his mother, at 20, joined an intelligence service amid the Holocaust to help Britain fight the Nazis. In 1978, while he studied law and politics at Cardiff University in Wales, he organized a protest of the Soviet Union’s oppression of Jews, and he later traveled to the country to visit families who’d been ostracized. During a stay in Israel, he demonstrated against the movement to resettle the West Bank. In the mid-1980s, he supported mine workers in their bitter dispute with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

It was around then that Jon fell for a girl from Philly, and in 1989 he moved with her to Pennsylvania to raise a family a half hour from Independence Hall, where the U.S. was founded.

A year later, Jon watched President George H.W. Bush sign the Immigration Act of 1990, a bill that the Republican praised for recognizing “the fundamental importance and historic contributions of immigrants to our country.” Jon applied for citizenship a few years later, because this was his home now and he wanted to vote for the people in charge of it.

He admired nothing more about the U.S. than the Constitution he’d studied before swearing his oath of allegiance. The rights it guaranteed made the country unlike any in the world, Jon thought, and he was proud to be part of it.

Now, in his 27th year as a citizen, he was staring at his phone, terrified that the same country was trying to strip him of those rights.

No copy of subpoena

Jon needed help, so a day or two after he received the email from Google, he called Judi Bernstein-Baker, who, at 80, remains one of Philadelphia’s most well-known immigration lawyers.

She was willing to offer advice, she told him, but first needed to see the subpoena.

“They didn’t send me the subpoena,” Jon explained over the phone.

“How do you challenge a subpoena you don’t have a copy of?” she asked.

Worse, he told her, Google had given him a single week to file a motion to quash the government’s demand.

Unless you’re rich, Bernstein-Baker recalled thinking, nobody can find an attorney to go to federal court in seven days.

Jon assumed the subpoena had been approved by a judge or grand jury, because he didn’t know any other kind existed, but when he called the federal court district mentioned in Google’s notice, a clerk told him they could find no trace of it.

Jon pored over Reddit posts and old news coverage, eventually working out on his own that the subpoena was not judicial, but administrative.

The U.S. government has issued such subpoenas for decades, but their use expanded, and became more controversial, after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. A vast range of agencies — from the FBI to the Labor Department — can deploy them for specific types of investigations.

Proponents describe administrative subpoenas as critical tools that allow investigators to avoid protracted judicial reviews to obtain information that could, for example, help them identify someone sexually exploiting a child or track down a suspected drug trafficker.

Speed is what makes them so useful, former and current federal investigators told the Post. With no external bureaucracy, the government can obtain phone, financial and internet records in days.

Detractors argue that the lack of independent oversight and the secrecy with which they can be wielded threaten core democratic principles.

“This vast administrative power has remained opaque even to those who receive these subpoenas and invisible to those it affects most,” Lindsay Nash, a professor and researcher, wrote for the Columbia Law Review last year.

For Jon, discovering the nature of his subpoena made it no easier to obtain.

Google had notified him from a “noreply” address and directed him to request a copy from Homeland Security but didn’t provide a phone number. Jon’s efforts to reach the agency led to a maddening, hours-long circuit of answering machines, dead numbers, and uninterested attendants.

“It is a rigged process, designed to keep people in the dark,” Jon wrote an attorney at a nonprofit in California that offered him basic guidance.

Google did not answer questions from the Post specific to Jon’s case or explain why it gave him only seven days to respond to a subpoena it didn’t provide.

The company is not required by law to inform users of government requests, but a spokesperson said it does unless it’s legally prohibited from doing so or in exceptional circumstances, such as when someone’s life is in jeopardy. Google can extend the seven-day deadline, the spokesperson said, though in Jon’s case, the company never told him that or provided a way to request more time.

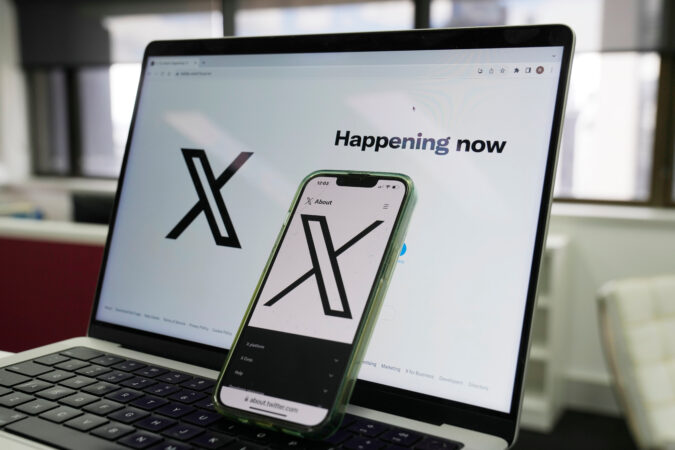

Like other large tech firms, Google regularly publishes “transparency reports” that show how many government demands for user data it receives, but the companies don’t differentiate between judicial and administrative subpoenas, despite their fundamental differences.

Both Google and Meta received a record number of subpoenas in the U.S. during the first half of last year, as Trump began his second term in office, according to the companies’ most recent reports. Google, which has shared subpoena data since 2012, was sent 28,622, a 15% increase over the previous six months.

Meta, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, and Snap say that they, like Google, alert their users to administrative subpoenas unless they’re barred from doing so or in extenuating circumstances.

T-Mobile and TikTok, in contrast, say they notify users when required to by law. Verizon and AT&T wouldn’t tell the Post whether they provide any notice, and X did not reply to questions.

Jon kept searching for answers as Google’s deadline passed.

In the case of the Instagram users posting about ICE raids, he read, the government dropped its case after the ACLU filed a 40-page legal challenge.

In a similar case in Pennsylvania, Homeland Security asked Meta to identify the people behind a Facebook and Instagram account that tracked ICE raids in Montgomery County. Federal attorneys argued in a court filing that the accounts invited scrutiny when they posted pictures of ICE agents’ faces, license plates, and weapons.

“John Doe, through his social media accounts, is threatening ICE agents to impede the performance of their duties,” the government told the judge in December.

A month later, it withdrew the subpoena, and the case was closed.

Even if courts decide that Homeland Security abused its authority and violated constitutional rights, legal experts doubt the agency will be forced to stop the practice.

The more Jon learned about administrative subpoenas, the more troubled he was that many Americans had never heard of them.

After leaving England, he had fallen into insurance work, but he’d begun his career in British law, representing social workers from some of London’s poorest neighborhoods. As he neared retirement, he signed up for a certificate program at Villanova University that trains people to help immigrants navigate a legal system that often feels overwhelming.

Now here he was, struggling to navigate the same system. But Jon wouldn’t let it go. He kept researching, calling, emailing.

“Obsessed,” his wife said.

“Beyond my personal situation, is the bigger question of how they misuse their powers to target innocent victims across the board,” he wrote one attorney. “If this goes unchallenged, we are all complicit or vulnerable in allowing the Government to abuse its powers.”

Police at the door

Through the window, his wife saw them coming.

“It’s the police!” she screamed.

Jon hurried downstairs. It was about 9:30 on the morning of Nov. 17. On his porch, he found a local officer, in uniform, with two men in slacks and sport coats.

“We’re with Homeland Security,” he recalled one of them saying.

They showed him their badges.

His breath quickened, but he tried not to panic. A diabetic now on Social Security, Jon stands 5-foot-6, and the few remaining hairs on his head turned gray years ago. He speaks in a plodding British accent, and unless he’s watching a Tottenham Hotspur soccer match, he hardly ever raises his voice.

But he’d seen videos of Homeland Security encounters that turned violent, even for women, teenagers, and old men.

Inside, he could hear the dog yelping and his wife shouting, “Don’t you have anything better to do?”

One of the federal agents showed him a copy of the email to Dernbach.

“We want to hear your side of the story,” he recalled one of them saying.

He told the men about Tthe Post’s investigation and his dismay over Homeland Security’s attempt to deport the Afghan who’d supported the U.S. war effort.

When they asked how he knew Dernbach’s email address, Jon, whose only social media is Facebook, told them he found it through a basic Google search.

He also shared the notice from Google, which, he said it seemed, they had not seen. Someone from Homeland Security’s headquarters in Washington had told their office to interview Jon, the men shared, though they didn’t give a name.

His message to Dernbach, he told them, was an opinion, protected by the First Amendment.

“This is as mild as one could possibly interpret,” he recalled saying.

The investigators agreed that the email broke no law, he said, but they pointed to his mentions of Russian roulette and the Taliban. Perhaps, they conjectured, the prosecutor felt threatened.

That was absurd, given the context, Jon thought, but he didn’t say that.

After about 20 minutes, the men thanked him for his time.

But Jon had one more question.

He sometimes returned to England to visit family, and he and his wife had planned to travel over Christmas to Puerto Rico for their 40th wedding anniversary.

“I hope this doesn’t mean I’m going to get stopped at the airport,” he said. “Am I on a list now?”

Of course not, he said the men told him. He had nothing to worry about.

Homeland Security demands

An online privacy expert gave Jon a little-known email address he could use to request the subpoena from Google, though the guy warned him he might not get a response. Jon tried it anyway.

That same day, Nov. 21, a Post reporter contacted Google about his case. Two hours after that — 22 days after Google notified Jon of the subpoena — the company provided him a copy, though the name of the official who authorized it had been redacted.

The investigators who questioned Jon told him Homeland Security couldn’t obtain his emails, documents, photos, or other content with an administrative subpoena, he said, but the breadth of what federal investigators did ask for shook him.

Among their demands, which they wanted dating back to Sept. 1: the day, time, and duration of all his online sessions; every associated IP and physical address; a list of each service he used; any alternate usernames and email addresses; the date he opened his account; his credit card, driver’s license, and Social Security numbers.

Then came another revelation three days later, when Google informed him that it had “not yet responded” to Homeland Security’s legal demand. Jon had assumed Google provided the government everything it asked for weeks earlier, well before the agents visited his home.

The company didn’t explain the delay to Jon or the Post.

“Our processes for handling law enforcement subpoenas are designed to protect users’ privacy while meeting our legal obligations,” a spokesperson told the Post. “We review all legal demands for legal validity, and we push back against those that are overbroad or improper, including objecting to some entirely.”

The ACLU agreed to represent Jon pro bono, filing a motion to quash in federal court on Monday to prevent Google from ever releasing his information. His attorneys accused the government of violating the statute that limits the use of administrative subpoenas for “immigration enforcement,” and the organization argued that Homeland Security had violated Jon’s right to free speech.

“It doesn’t take that much to make people look over their shoulder, to think twice before they speak again,” said Nathan Freed Wessler, one of the ACLU attorneys. “That’s why these kinds of subpoenas and other actions — the visits — are so pernicious. You don’t have to lock somebody up to make them reticent to make their voice heard. It really doesn’t take much, because the power of the federal government is so overwhelming.”

The knowledge that Google never sent the government the information it requested both comforted and unnerved Jon, because it meant that those two federal agents had tracked him down some other way.

He’d noticed that on the subpoena’s final page, the government had asked Google not to tell him about it.

“Any such disclosure,” the message read, “will impede the investigation and thereby interfere with the enforcement of federal law.”

Google had ignored that request, too, and he was relieved. But it made Jon wonder.

What if the U.S. government had investigated him in other ways? And what if it still was?

No real safeguards

One morning in early December, Jon shared his story with two acquaintances as they rode the train into Philadelphia for an interfaith protest, unrelated to the subpoena, outside ICE’s field office.

“They don’t have to go into court,” Jon said of Homeland Security. “They don’t have to bother spending the money to do that. They just rely on the acquiescence of these companies to do their bidding.”

“Clearly they’re doing it to further a particular agenda,” David Mosenkis said from the seat in front of Jon.

“To intimidate,” Jon interjected.

“That’s what they want,” said Rabbi Leah Wald, sitting next to Mosenkis. “They want everyone to be scared, right?”

Jon thought back to how it had all started, with the note to Dernbach.

“There are no real safeguards anymore,” he said, “until people recognize that we’re all potential targets.”

Mosenkis, 65, stared out the window into the morning sunlight, his eyes drifting across a city where he’d demonstrated against perceived injustices for more than three decades.

“I organize this weekly gathering, protest,” he said, “called ‘We the People Wednesdays.’”

The group took on a different topic each week — “Election integrity,” “Defending the Constitution against domestic enemies” — and wrote postcards to public officials.

Their letters, Mosenkis realized, were no different from Jon’s email.

“This is exactly the kind of thing we do,” he said. “And we tell people to sign their names and ZIP codes.”

He shook his head. He rubbed his forehead.

“If that’s subject to surveillance,” Mosenkis said, “then anything could be.”

The train soon pulled into the city, where they gathered in the cold with about 100 other people outside the ICE office. On the sidewalk, they listened to a rabbi recall the Torah’s command to love the stranger. Jon waved signs that read “STOP ICE RAIDS” and “LOVE THY NEIGHBOR.”

In the weeks that followed, he tried to turn his attention to the holidays and his anniversary trip with his wife.

Just before Christmas, the couple left for Puerto Rico. At the airport outside San Juan, they waited at baggage claim until every other passenger had left. Their luggage, they were told, remained in Philadelphia.

“Is this a coincidence?” he asked his wife.

The bags arrived at their cruise ship later that night, and the couple opened them in the cabin.

Nothing looked out of place in his wife’s, but in Jon’s, he found a notice from the Transportation Security Administration.

“Your bag,” the standard form read, “was among those selected for physical inspection.”

It did not explain why.

Jon didn’t want to talk about what it might mean, not then. So he took a photo, closed the bag and tried to go to sleep.

— — –

Drew Harwell and Nate Jones contributed to this report.

John Woodrow Cox can be reached securely on Signal at johnwoodrowcox.01.